By Lisa Hildebrand, PhD student, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, & Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

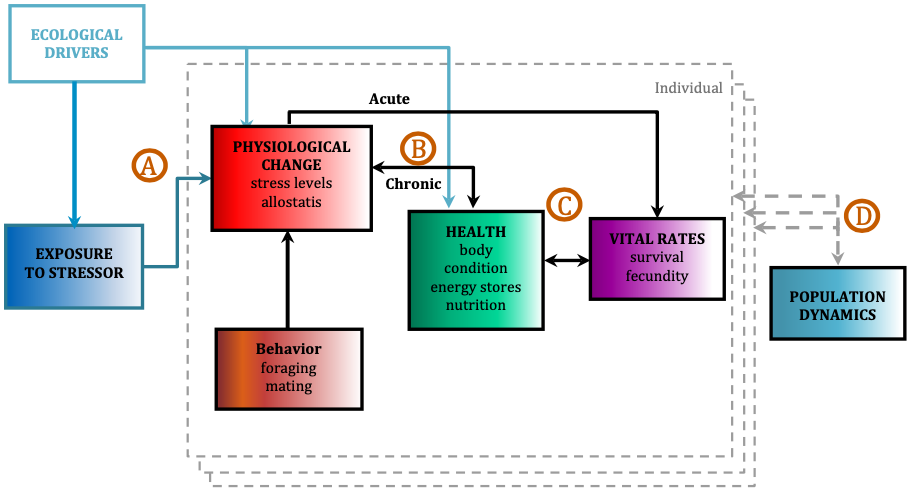

Predators have high energetic requirements that must be met to ensure reproductive success and population viability. For baleen whales, this task is particularly challenging since their foraging seasons are typically limited to short temporal windows during summer months when they migrate to productive high latitude environments. Foraging success is a balancing act whereby baleen whales must maximize the amount of energy they intake, while minimizing the amount of energy they expend to obtain food. Maximization of energy intake can be achieved by targeting the most beneficial prey. How beneficial a particular prey type (or prey patch) is can depend on a number of factors such as abundance, density, quality, size, and availability. Determining why baleen whales target particular prey types or patches is an important factor to enhance our understanding of their ecology and can ultimately aid in informing their management and conservation.

The GEMM Lab has several research projects in Newport and Port Orford, Oregon, on the Pacific Coast Feeding Group (PCFG), which is a sub-group of gray whales from the Eastern North Pacific (ENP) population. While ENP gray whales feed in the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas (Arctic) in the summer months, the PCFG utilizes the range from northern California, USA to northern British Columbia, Canada. Our work to date has revealed a number of new findings about the PCFG including that they successfully gain weight during the summer on Oregon foraging grounds (Soledade Lemos et al. 2020). Furthermore, females that consistently use the PCFG range as their foraging grounds have successfully reproduced and given birth to calves (Calambokidis & Perez 2017). Yet, the abundance of the PCFG (~250 individuals; Calambokidis et al. 2017) is two orders of magnitude smaller than the ENP population (~20,000; Stewart & Weller 2021). So, why do more gray whales not use the PCFG range as their foraging grounds when it provides a shorter migration while also allowing whales to meet their high energetic requirements and ensure reproductive success? There are several hypotheses regarding this ecological mystery including that prey abundance, density, quality, and/or availability are higher in the Arctic than in the PCFG range, thus justifying the much larger number of gray whales that migrate further north for the summer feeding season.

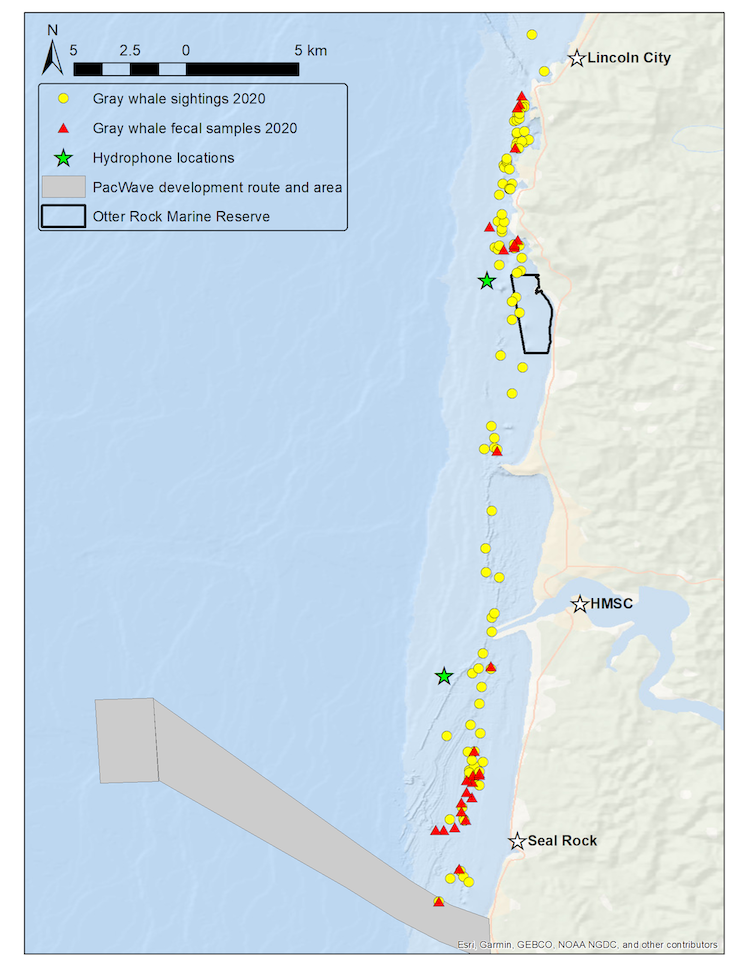

Our recent paper in Frontiers in Marine Science addressed the hypothesis that prey quality in the Arctic is higher than that of PCFG prey. To test this hypothesis, we first determined the quality (energetic value) of nearshore Oregon zooplankton species that PCFG gray whales are assumed to feed on (based on observations of fine-scale spatial and temporal overlap of foraging gray whales and sampled zooplankton). We obtained prey samples from nearshore reefs along the Oregon coast (Figure 1) as part of the GRANITE project using a light trap, which is a modified water jug with a weight and two floats attached to it, allowing the trap to sit approximately 1 meter above the seafloor. The trap contained a light which attracted zooplankton and effectively captured epibenthic prey of gray whales. Traps were left to soak overnight in locations where gray whales had been observed feeding extensively and collected the following morning. After identifying each specimen to species level and sorting them into reproductive stages, we used a bomb calorimeter to determine the caloric content of each species by month, year, and reproductive stage. We then compared these values to the literature-derived caloric value of the predominant benthic amphipod species that ENP gray whales feed on in the Arctic. These comparisons allowed us to extrapolate the caloric values gained from each prey type to estimated energetic requirements of pregnant and lactating female gray whales (Villegas-Amtmann et al. 2017).

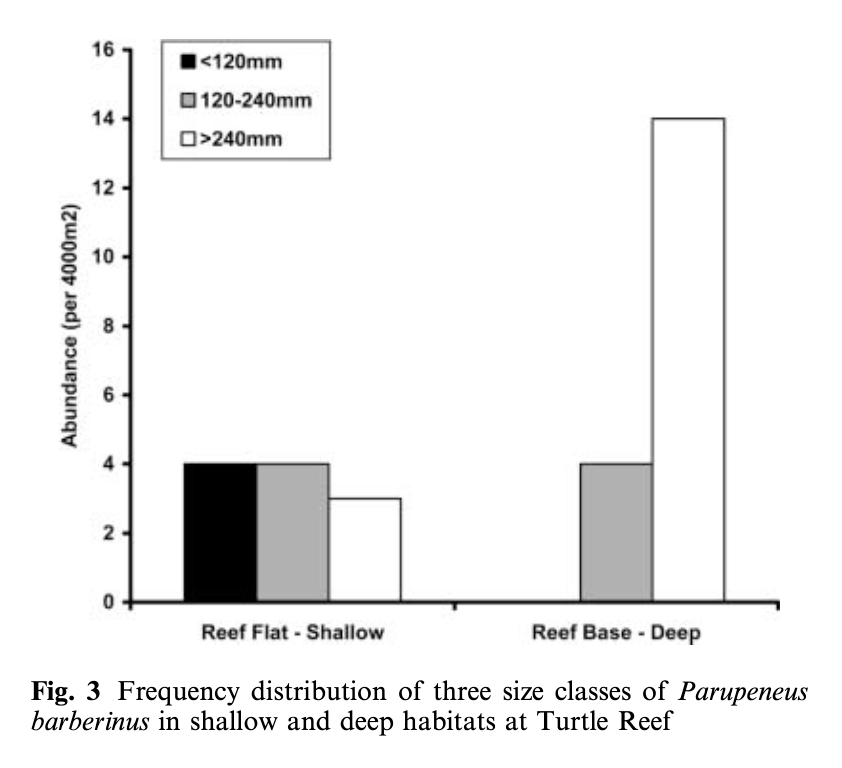

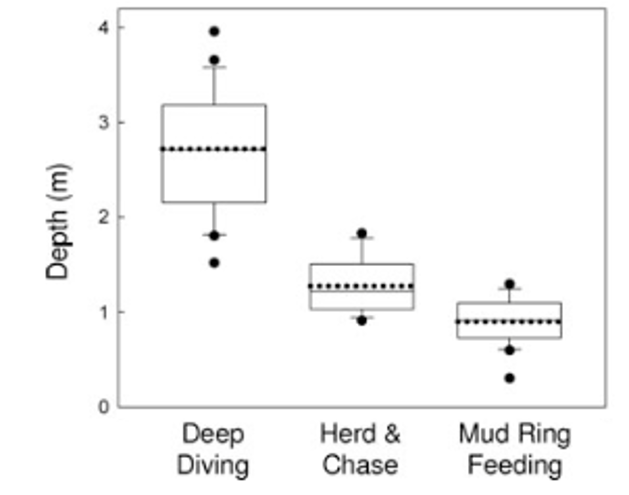

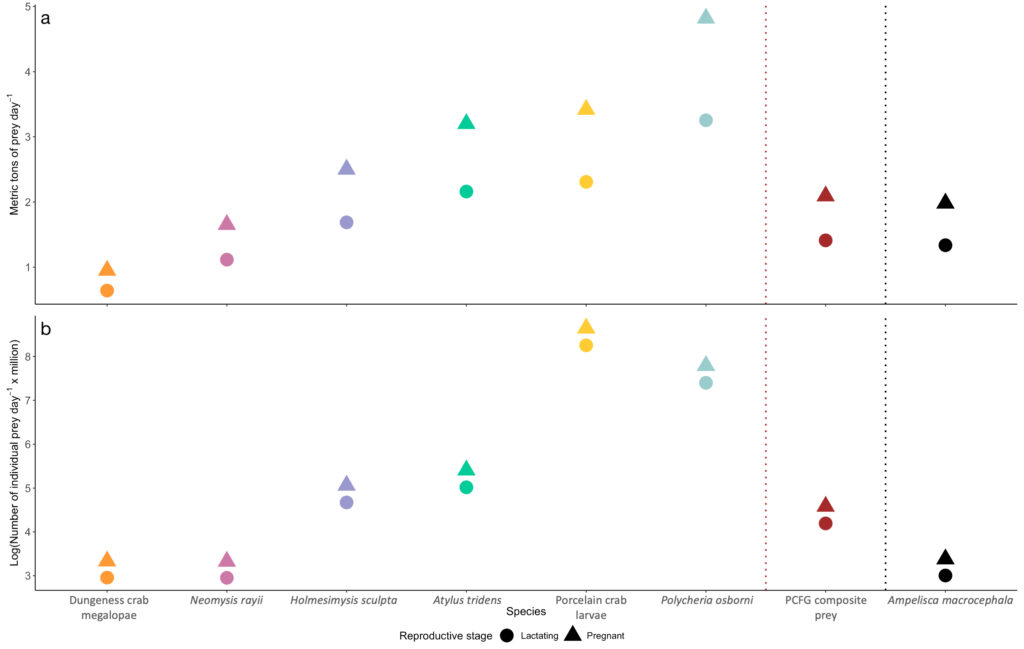

So, what did we find? Our sampling along the Oregon coast revealed six predominant zooplankton species: two mysid shrimp (Neomysis rayii, Holmesimysis sculpta), two amphipods (Atylus tridens, Polycheria osborni), and two types of crab larvae (Dungeness crab megalopae, porcelain crab larvae). These six Oregon prey species showed significant differences in their caloric values, with N. rayii and Dungeness crab megalopae having significantly higher calories per gram than the other prey species (Figure 2), though Dungeness crab megalopae stood out as the caloric gold mines for feeding gray whales in the PCFG range. Furthermore, month and reproductive stage also influenced the caloric content of some prey species, with gravid (aka pregnant) female mysid shrimp significantly increasing in calories throughout the summer (Figure 3).

The comparison of our Oregon prey caloric values to the predominant Arctic amphipod (Ampelisca macrocephala) proved our hypothesis wrong: Arctic amphipods do not have higher caloric value than Oregon prey, which would have help to explain why many more gray whales feed in the Arctic. We found that two Oregon prey species (N. rayii and Dungeness crab megalopae) have higher caloric values than A. macrocephala. If we translate the caloric contents of these prey to gray whale energetic needs, these differences mean that lactating and pregnant gray whales feeding in the PCFG area would need between 0.7-1.03 and 0.22-0.33 metric tons of prey less per day if they fed on Dungeness crab megalopae or N. rayii, respectively, than a whale feeding on Arctic A. macrocephala (Figure 4).

If quality were the only prey metric that gray whales used to evaluate which food to eat, then it would make very little sense for so many gray whales to migrate to the Arctic when there are prey types of equal and greater quality available to them in the PCFG range. However, quality is not the only metric that influences gray whale foraging decisions. We therefore posit that the abundance, density, and availability of benthic amphipods in the Arctic are higher than the prey species found in the PCFG range. In fact, knowledge of the pulsed reproductive cycle of Dungeness and porcelain crabs allows us to conclude that the larvae of these two species are only available for a few weeks in the late spring and early summer on the Oregon coast. While mysid shrimp, such as N. rayii, are continuously available in the PCFG range throughout the summer, they may occur in less dense and more patchy aggregations than Arctic benthic amphipods. However, current estimates of prey density and abundance for either region are not available, and we do not have data on the energetic costs of the different foraging strategies. While there are still several unknowns, we have documented that higher prey quality in the Arctic is not the reason for the difference in gray whale foraging ground use in the eastern North Pacific.

References

Calambokidis, J., & Perez, A. 2017. Sightings and follow-up of mothers and calves in the PCFG and implications for internal recruitment. IWC Report SC/A17/GW/04 for the Workshop on the Status of North Pacific Gray Whales (La Jolla: IWC).

Calambokidis, J., Laake, J., & Perez, A. 2017. Updated analysis of abundance and population structure of seasonal gray whales in the Pacific Northwest, 1996-2015. IWC Report SC/A17/GW/05 for the Workshop on the Status of North Pacific Gray Whales (La Jolla: IWC).

Soledade Lemos, L., Burnett, J. D., Chandler, T. E., Sumich, J. L., & Torres, L. G. 2020. Intra- and inter-annual variation in gray whale body condition on a foraging ground. Ecosphere 11(4):e03094.

Stewart, J. D., & Weller, D. W. 2021. Abundance of eastern North Pacific gray whales 2019/2020. Department of Commerce, NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SWFSC-639. United States: NOAA. doi:10.25923/bmam-pe91.

Villegas-Amtmann, S., Schwarz, L. K., Gailey, G., Sychenko, O., & Costa, D. P. 2017. East or west: the energetic cost of being a gray whale and the consequence of losing energy to disturbance. Endangered Species Research 34:167-183.