By Nichola Gregory, B.S. Earth Science, College of Earth, Ocean, & Atmospheric Sciences, GEMM Lab Port Orford Intern

As a recent OSU graduate from the College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences (CEOAS), I gained both knowledge regarding oceanographic and biological concepts through my coursework, and also a passion to be involved in projects that work towards bettering the natural world. Currently, I am pursuing a GIS (Geographic Information System) certificate from Portland Community College. The choice to continue my education with this certification was driven by its applicability as well as my desire to equip myself with skill sets that are applicable in addressing questions in marine science. This desire leads to the primary reason I was drawn to the TOPAZ/ JASPER projects that I am fortunate to be a part of this summer. These projects located in Port Orford have allowed me to become more familiar with various softwares and instruments used within marine sciences, and the instrument that I have been most excited to learn more about this summer is the theodolite.

My first introduction to the theodolite was during my biology of marine mammals course in Newport where PhD student Lisa Hildebrand (then Master’s student and graduate student leader of the Port Orford project since 2018) visited us in Depoe Bay with the instrument. That day, I was intimidated yet intrigued by how theodolites work and learned from Lisa that it can be used to create ‘tracklines’ of gray whale movements.

Now that the 2022 field season is underway, I’ve spent the last couple weeks at the Port Orford Field Station under the guidance of Master’s student Allison Dawn where I have gained familiarity with operating the theodolite (or as we affectionately call it, the Theo). I have also learned how vital of a tool it can be in helping us understand the habits and ecology of PCFG gray whales that visit the Oregon coast.

Figure 1: Four out of five members of the 2022 team pictured during cliff training. From left to right: Charlie watches whales with binoculars, Zoe learns how to use Pythagoras software for trackline creation, and Allison instructs me on how to use the theodolite. Photo credit: Luke Donaldson

Figure 2: A basic diagram of a digital theodolite. Top “Theo” pictured is facing out toward the object while the bottom “Theo” shows the user side. Diagram credit: Johnson Level & Tool Mfg. Co

Theodolites became popular in the early 1800’s and have been used for land surveying since. They combine optical plummets, a bubble level, and graduated circles to find vertical and horizontal angles while surveying. For a more visual introduction to theodolite and some of its uses, check out this link to a youtube video.

When the cliff team begins the day, their primary objective is to set up the theodolite and be prepared to track the locations and movements of gray whales. First, the surveying point (which is used to ensure repeatability of station location) is placed on the ground to position the tripod and theodolite. Then, once the tripod is set up and theodolite attached, leveling the instrument takes place. The 3 screws on the base plate of the Theo allow for leveling, which is of utmost importance so that the instrument is perfectly level with the horizon. The Theo has two bubble levelers to promote accuracy while moving the tripod legs as well as the leveling screws. Once the instrument is level, we complete the “start fix”, which is our first data point for each day and used as our reference point. The telescope includes an eyepiece for the user and an objective lens with internal mirrors to magnify the object(s) being viewed. Now we are ready to start fixing whale locations! And while the set up involved with “Theo” can be difficult to remember and tedious (leveling specifically) it has become somewhat automatic after a few weeks of practice.

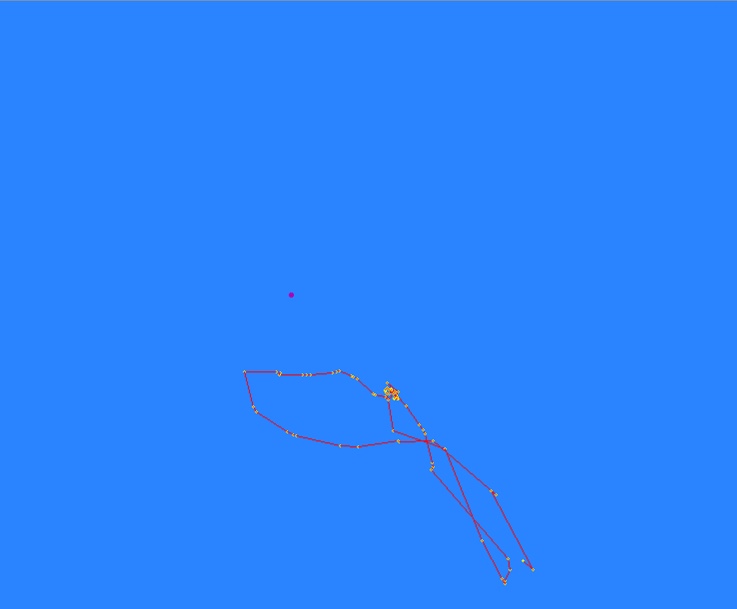

After a productive day with many whale fixes, a small map (Figure 3) is made on the associated computer program “Pythagoras”. This map shows the station (“Theo”), the reference point, and the relative location and coordinates of each fix made. The tracklines are then analyzed to learn more about movement and behavior of specific whale individuals (read Lisa’s blog here for more information!). We also carefully outline kelp patches with many “fixes” so we can create maps of kelp cover in our study areas. This year we are seeing more bull kelp compared to 2021, but stay tuned for more details about these changes from intern Luke Donaldson’s upcoming blog!

Figure 3: An example of a trackline map made in Pythagoras after gray whale fixes are made. This specific trackline shows a whale coming into Mill Rocks to forage, moving past the cliff station toward Tichenor Cove, and then making its way back to Mill Rocks.

Due to this amazing instrument, the GEMM lab has non-invasively tracked many whales over the many previous field seasons. Two whales that this year’s team has grown particularly fond of are named “Buttons” and “Rugged”. Both have visited Port Orford numerous times over the past couple weeks, giving us the chance to get practice with creating tracklines while also capturing up-to-date ID photos. Buttons is regularly documented along the Oregon coast and is such a local favorite that there is an honorary Port Orford Public Library Card in his name! Rugged also showed up two weeks ago with a brand new marking that is likely a propeller scar. In addition to seeing a greater number of kelp patches, we have already obtained more whale trackline data than the entirety of last year’s season. I hope this means we are observing a recovering ecosystem, and a positive future for Port Orford, through the lens of the Theodolite.

Figure 4: A photo captured of Rugged, our first whale sighting of the 2022 season. Photo credit: Allison Dawn

After being in Port Orford for a couple weeks now, with the first few days of proper sampling behind me, I can tell my time here will be time well spent. Not only have I become familiar with a new instrument, I have learned a great deal in how science in the field is conducted and how broad a project can become. Specifically, I am impressed by the volume of data that is collected at the 12 unique kayak sampling stations on any given field day –secchi depth, water depth & chemistry, underwater footage, and zooplankton. These data complement the data cliff team provides, which, in addition to whale movement data, includes Beaufort Sea State, tidal height, and weather. I now appreciate how important it is to gather as much information as possible in order to find connections between the environment, gray whales, and their prey, even if those connections are not obvious to us today.

Another lesson I’ve found invaluable during this experience is my growing belief in myself and abilities. Prior to this summer, I had minimal experience on the water, mostly limited to rivers and lakes. But after being in Port Orford for a few weeks, I have learned that something that once seemed daunting can become enjoyable. I think almost every young person in science finds themselves in a state of “imposter syndrome” at some point, where despite great education and experiences, they fall short in self confidence. Time spent on the cliff, kayak and lab has helped affirm that marine science is where I belong. Perhaps even more impactful are the experiences I have had while navigating the learning curve of these skills. I hope to keep this growth-mindset and push through future experiences that feel awkward or scary in order to reach my goals and find my place in marine sciences.

Did you enjoy this blog? Want to learn more about marine life, research and conservation? Subscribe to our blog and get weekly updates and more! Just add your name into the subscribe box below!

References

All about theodolites. Levels, Laser Levels and Measuring Tool Mfg Company Johnson Level. (n.d.). Retrieved August 1, 2022, from https://www.johnsonlevel.com/News/TheodolitesAllAboutTheodo

Leonid Nadolinets, Eugene Levin, Daulet Akhmedov. 12 Jun 2017, Theodolites from:

Surveying Instruments and Technology CRC Press

Retrieved August 1, 2022, from

https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315153346-3

NMAH: Surveying & geodesy: Theodolite. NMAH | Surveying & Geodesy | Theodolite. (n.d.). Retrieved August 2, 2022, from https://amhistory.si.edu/surveying/type.cfm?typeid=19