By Rachel Kaplan1 and Dawn Barlow2

1PhD student, Oregon State University College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences and Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

2PhD Candidate, Oregon State University Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

“Hurry up and wait.” A familiar phrase to anyone who has conducted field research. A flurry of preparations, followed by a waiting game—waiting for the weather, waiting for the right conditions, waiting for unforeseen hiccups to be resolved. We do our best to minimize unknowns and unexpected challenges, but there is always uncertainty associated with any endeavor to collect data at sea. We cannot control the whims of the ocean; only respond as best we can.

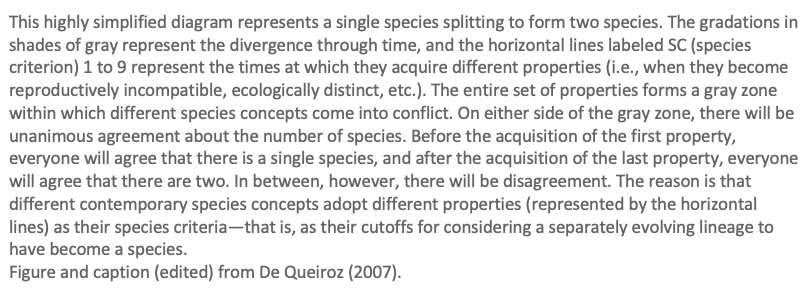

On 15 February 2021, we were scheduled to board the NOAA Ship Bell M. Shimada as marine mammal observers for the Northern California Current (NCC) ecosystem survey, a recurring research cruise that takes place several times each year. The GEMM Lab has participated in this multidisciplinary data collection effort since 2018, and we are amassing a rich dataset of marine mammal distribution in the region that is incorporated into the OPAL project. February is the middle of wintertime in the North Pacific, making survey conditions challenging. For an illustration of this, look no further than at the distribution of sightings made during the February 2018 cruise (Fig. 1), when rough sea conditions meant only a few whales were spotted.

Now, this is February 2021 and the world is still in the midst of navigating the global coronavirus pandemic that has affected every aspect of our lives. The September 2020 NCC cruise was the first NOAA fisheries cruise to set sail since the pandemic began, and all scientists and crew followed a strict shelter-in-place protocol among other COVID risk mitigation measures. Similarly, we sheltered in place in preparation for the February 2021 cruise. But here’s where the weather comes in yet again. Not only did we have to worry about winter weather at sea, but the inclement conditions across the country meant our COVID tests were delayed in transit—and we could not board the ship until everyone tested negative. By the time our results were in, the marine forecast was foreboding, and the Captain determined that the weather window for our planned return to port had closed.

So, we are still on shore. The ship never left the dock, and NCC February 2021 will go on the record as “NAs” rather than sightings of marine mammal presence or absence. So it goes. We can dedicate all our energy to studying the ocean and these spectacularly dynamic systems, but we cannot control them. It is an important and humbling reminder. But as we have continued to learn over the past year, there are always silver linings to be found.

Even though we never made it to the ship, it turns out there’s a lot you can get done onshore. Dawn has sailed on several NCC cruises before, and one of the goals this time was to train Rachel for her first stint at marine mammal survey work. This began at Dawn’s house in Newport, where we sheltered in place together for the week prior to our departure date.

We walked through the iPad program we use to enter data, looked through field guides, and talked over how to respond in different scenarios we might encounter while surveying for marine mammals at sea. We also joined Solene, a postdoc working on the OPAL project, for a Zoom meeting to edit the distance sampling protocol document. It was great training to discuss the finer points of data collection together, with respect to how that data will ultimately be worked into our species distribution models.

The February NCC cruise is famously rough, and a tough time to sight whales (Fig. 1). This low sighting rate arises from a combination of factors: baleen whales typically spend the winter months on their breeding grounds in lower latitudes so their density in Oregon waters is lower, and the notorious winter sea state makes sighting conditions difficult. Solene signed off our Zoom call with, “Go collect that high-quality absence data, girls!” It was a good reminder that not seeing whales is just as important scientifically as seeing them—though sometimes, of course, it’s not possible to even get out where you can’t see them. Furthermore, all absence data is not created equal. The quality of the absence data we can collect deteriorates along with the weather conditions. When we ultimately use these survey data to fuel species distribution models, it’s important to account for our confidence in the periods with no whale sightings.

In addition to the training we were able to conduct on land, the biggest silver lining came just from sheltering in place together. We had only met over Zoom previously, and spending this time together gave us the opportunity to get to know each other in real life and become friends. The week involved a lot of fabulous cooking, rainy walks, and an ungodly number of peanut butter cups. Even though the cruise couldn’t happen, it was such a rich week. The NCC cruises take place several times each year, and the next one is scheduled for May 2021. We’ll keep our fingers crossed for fair winds and negative COVID tests in May!