By Serina Lane, GEMM Lab NSF REU Intern, Georgia Gwinnett College

Hello, everyone! My name is Serina and I’m a Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) Intern at the Hatfield Marine Science Center (HMSC) this summer. I’ve had a love for the ocean for as long as I can remember. Honestly, it started off with just dolphins, but I soon started to realize that the ocean is full of fascinating creatures!

How I ended up here…well, I’ve never been to Oregon, I’m escaping the hot weather of Georgia, but I’m also getting to interact with like-minded marine biologists and experienced individuals at an amazing marine laboratory. At the age of 29, I’m also an older undergraduate student, and I will be graduating soon! I took a very long break from academics and coming back was hard, especially switching from business to biology. I have participated in surveys that asked how I felt about the statement “I am a scientist,” along with the degrees of agree and disagree. For most of my undergraduate career, I picked “slightly disagree”. I was getting great grades, but I did not feel like I was ever going to be able to accomplish the type of work scientific papers are written about. I really felt the need to gain more experience in the career path I intended to follow. All of these are the whirlwind ingredients that went into applying for the HMSC REU Internship at OSU! I’m being mentored by the lovely Natalie Chazal and Leigh Torres, and I am grateful for the opportunity and very excited to experience everything Hatfield has to offer. A little over a week of being here, I already feel my answer sliding from “neutral” to even “slightly agree”. There is still so much to learn!

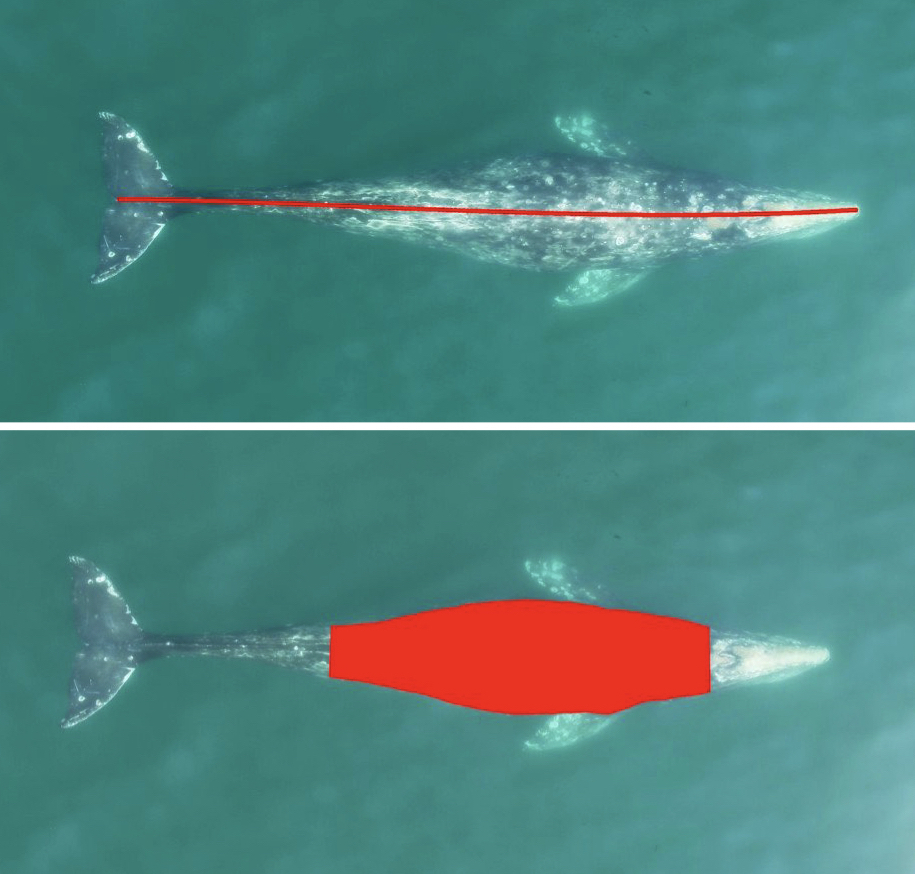

The project I’m helping with is analyzing the scarring and skin conditions of Eastern North Pacific gray whales alongside the GRANITE team. My job will be analyzing over 100,000 pictures from the past eight years to detect various scars and potential skin conditions (yes, the comma is in the correct spot and no, there are no extra 0’s). Scars can come from a variety of sources such as boat propellers, fishing gear, and killer whales! A study conducted by Corsi et al. consisted of documenting killer whale rake marks (bites, essentially) on different types of whales in the eastern North Pacific. Their results showed that gray whales had the highest percentage of observed rake marks in sighted individuals, and provided insight into why body sections of observed marks are important. Most baleen whales had rake marks predominantly on their flukes, because they are often used for defense and if fleeing, are the closest area to bite. Fascinatingly, Corsi et al. consider that the higher occurrences of gray whale rake marks are due to killer whales adopting species-specific hunting approaches. Gray whales have predictable migratory routes, and we already know how intelligent killer whales can be. If I knew a truck had a specific delivery route and I could wait to intercept a fresh delivery of Krispy Kreme donuts, why wouldn’t I?

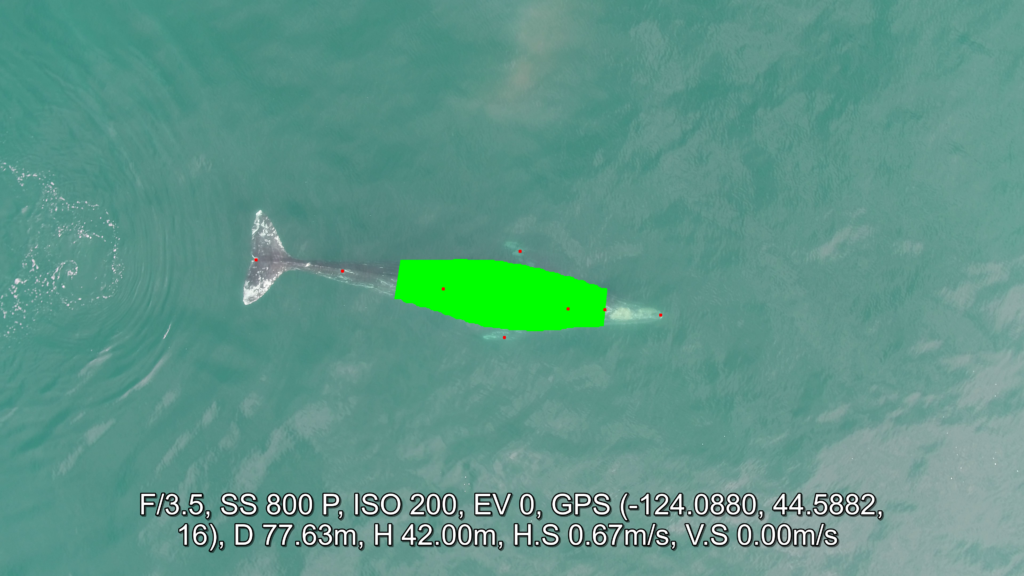

Donuts aside, I’ll also be categorizing where the scars/skin conditions are located – for example, certain regions on the tail (like above) or on their left or right back (often due to boat collisions). Then I’ll define what I believe to be the source of scarring and rate my confidence in that decision based on the photo. Now, not all of the photos are clear enough for me to make informed decisions, so realistically I could end up with only a few hundred usable photos. At the end of the summer, we’ll gather the results and compare the different rates of scarring sources and the body parts where they occurred, and analyze any patterns in skin conditions, such as whether a skin condition has worsened or improved on an individual we have sighted multiple times over the years.

Surprisingly, cetaceans can heal deep wounds on their own without medical intervention. Scientists have discovered that compounds in their blubber layer, such as organohalogens and isovaleric acid, may naturally fight off infections and help wounds heal faster. Unlike humans and other terrestrial animals that form scabs when injured, cetaceans develop a different protective layer over their wounds. This layer consists of degenerative cells mixed with tiny bubbles and covers the injured area. This unique adaptation might help protect the wound from seawater and other environmental factors. While there have been studies on how surface wounds heal in captive dolphins and whales, there’s still much to learn about how these animals heal large, deep wounds. Understanding how wounds heal can help us to more accurately assess the frequency at which whales are wounded, whether it be from fishing gear or boats, to cookie cutter sharks or killer whales.

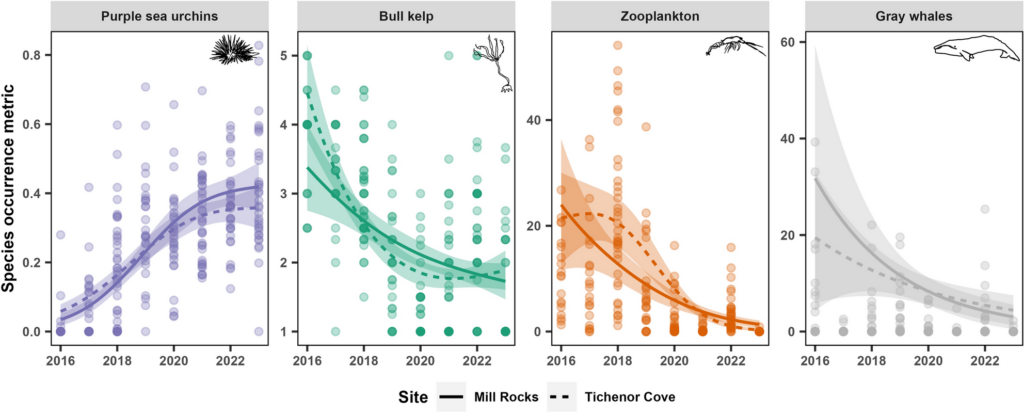

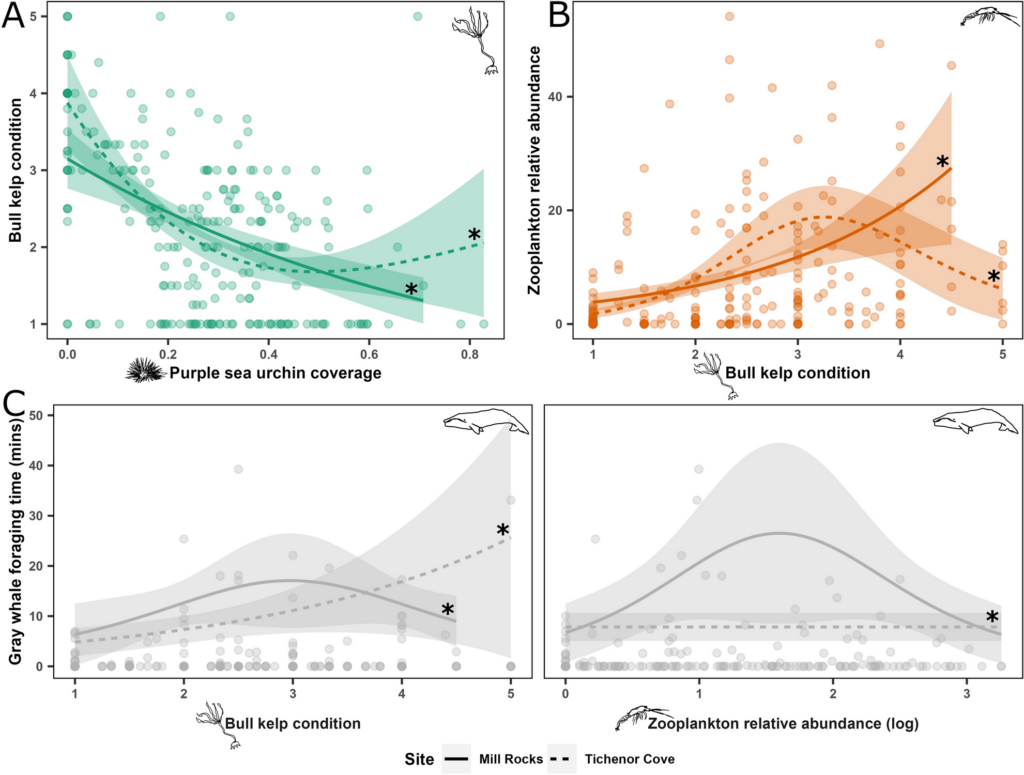

It seems like a lot, and it is, but our ultimate goal is to assess the effects that scarring and skin conditions can have in the ecology of marine megafauna. Assessing the individual gray whales in the photos can provide a bigger picture of the health of a whole population. We can also look for any patterns of skin conditions between mother and calf, individuals that are around each other often, adults and juveniles, or males and females. Scars may also play a role in a population’s health. If a gray whale had an open wound previously, did it develop into a skin condition? Did a skin condition worsen? Did it leave them more vulnerable to predators? These are the questions we would like to elaborate on with this research. A great read on this topic was conducted by Dawn R. Barlow, Acacia L. Pepper and Leigh G. Torres, which will be in the references below (Barlow et al., 2019). A better understanding of potential patterns is a better assessment of our current marine management practices. Is it enough, or do we need to change and do more?

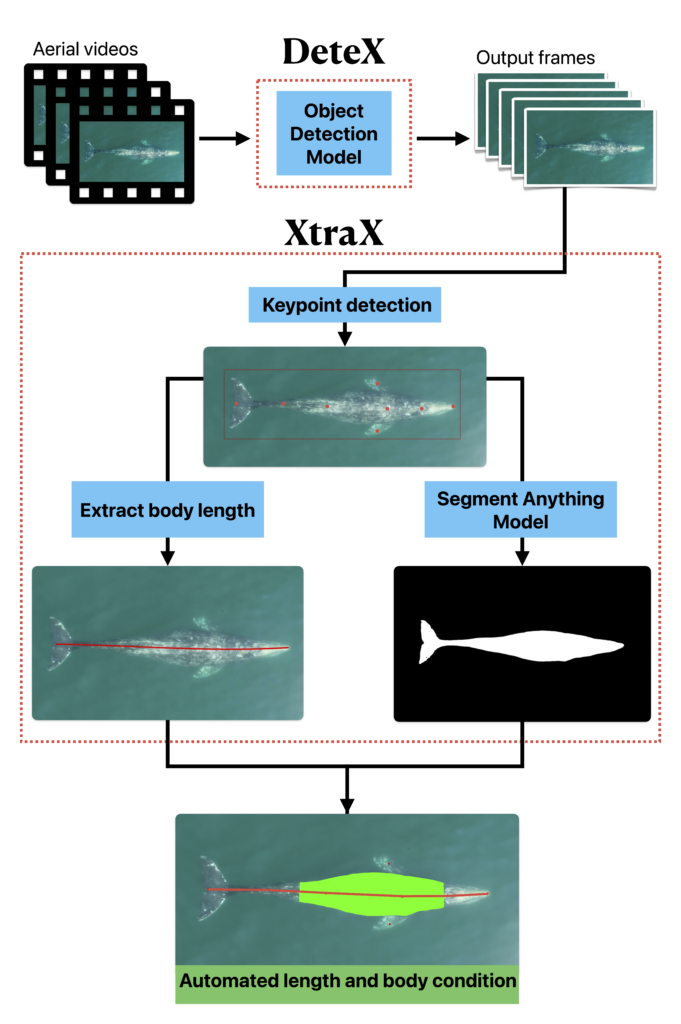

Okay, lastly, let’s talk about artificial intelligence (AI). Would using AI methods for this project make our lives easier? Yes. If we could train AI to accurately identify specific scars and skin conditions, our 100,000 photos could be done within minutes. For my job security, woo no AI! But on a serious note, this approach could free up time that could be spent on other efforts, or speed up the process of assessing marine management. However, we gain so much by reviewing the photos ourselves which is still important to do when training AI on what specifics to search for. Over the summer, I’m going to get to know different whales and see how they may change over 8 years, just by their pictures. My excitement grew as soon as I looked at my first 3 gray whales and learned their names. It’s forever important to remember that we can always learn from sharing connections with the organisms we study and interact with. We share the same planet and we have to work together to preserve it. I thank you all for taking a trip through our summer research with me and I hope to meet some of you around Hatfield!

References

Barlow, D. R., Pepper, A. L., & Torres, L. G. (2019a). Skin deep: An assessment of New Zealand blue whale skin condition. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00757

Bradford, A. L., Weller, D. W., Ivashchenko, Y. V., Burdin, A. M., & Brownell, Jr, R. L. (2009). Anthropogenic scarring of Western Gray Whales (Eschrichtius robustus). Marine Mammal Science, 25(1), 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2008.00253.x

Corsi, E., Calambokidis, J., Flynn, K. R., & Steiger, G. H. (2021). Killer whale predatory scarring on Mysticetes: A comparison of rake marks among blue, humpback, and gray whales in the eastern North Pacific. Marine Mammal Science, 38(1), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.12863

NOAA. (2020, April 4). Fisheries of the United States. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/sustainable-fisheries/fisheries-united-states

Hamilton, P. K., & Marx, M. K. (2005). Skin lesions on North Atlantic right whales: Categories, prevalence and change in occurrence in the 1990s. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 68, 71–82. https://doi.org/10.3354/dao068071

Pettis, H. M., Rolland, R. M., Hamilton, P. K., Brault, S., Knowlton, A. R., & Kraus, S. D. (2004). Visual health assessment of north atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) using photographs. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 82(1), 8–19. https://doi.org/10.1139/z03-207

Silber, G. K., Weller, D. W., Reeves, R. R., Adams, J. D., & Moore, T. J. (2021). Co-occurrence of gray whales and vessel traffic in the North Pacific Ocean. Endangered Species Research, 44, 177–201. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01093 Sun, L., Engle, C., Kumar, G., & van Senten, J. (2022). Retail market trends for Seafood in the United States. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, 54(3), 603–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/jwas.12919