By Solène Derville, Postdoc, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Science, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

Today let me take you on a journey into the tropical waters of the Indo-Pacific Ocean, far from Oregon’s beautiful coasts. Although I have been working as a postdoc on the OPAL project for a year, the pandemic has prevented me from moving to the US as planned. Like so many around the globe, I have been working remotely from my study area (Oregon coastal waters), imagining my study species (blue, fin and humpback whales) gently swimming and feeding along the productive California Current system. One day, I’ll get to see these amazing animals for real, that’s for sure.

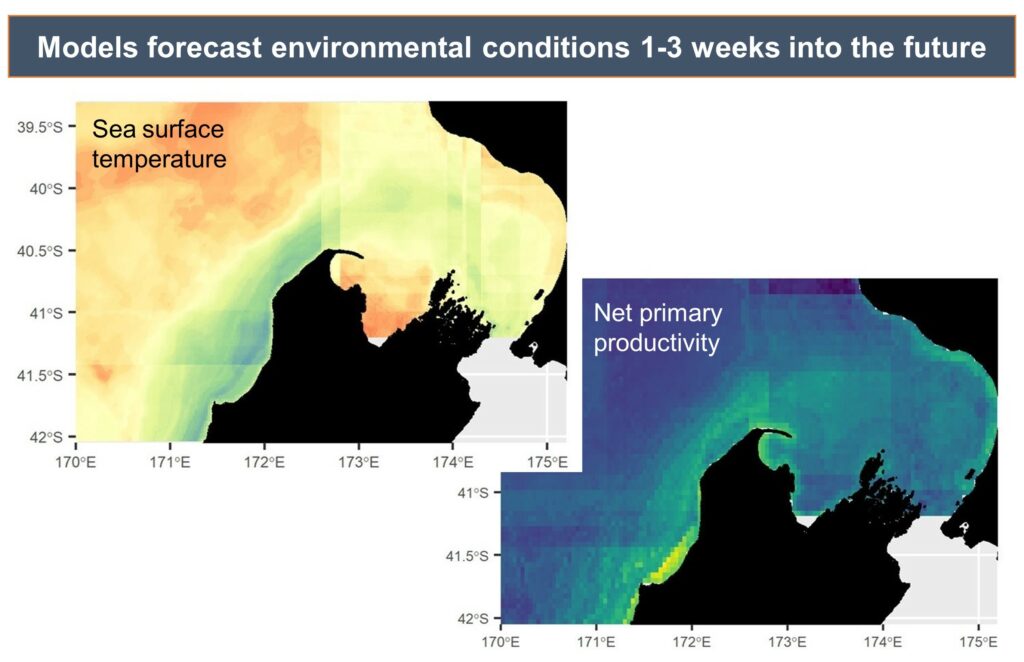

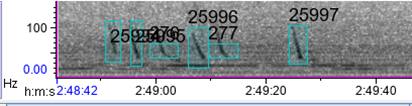

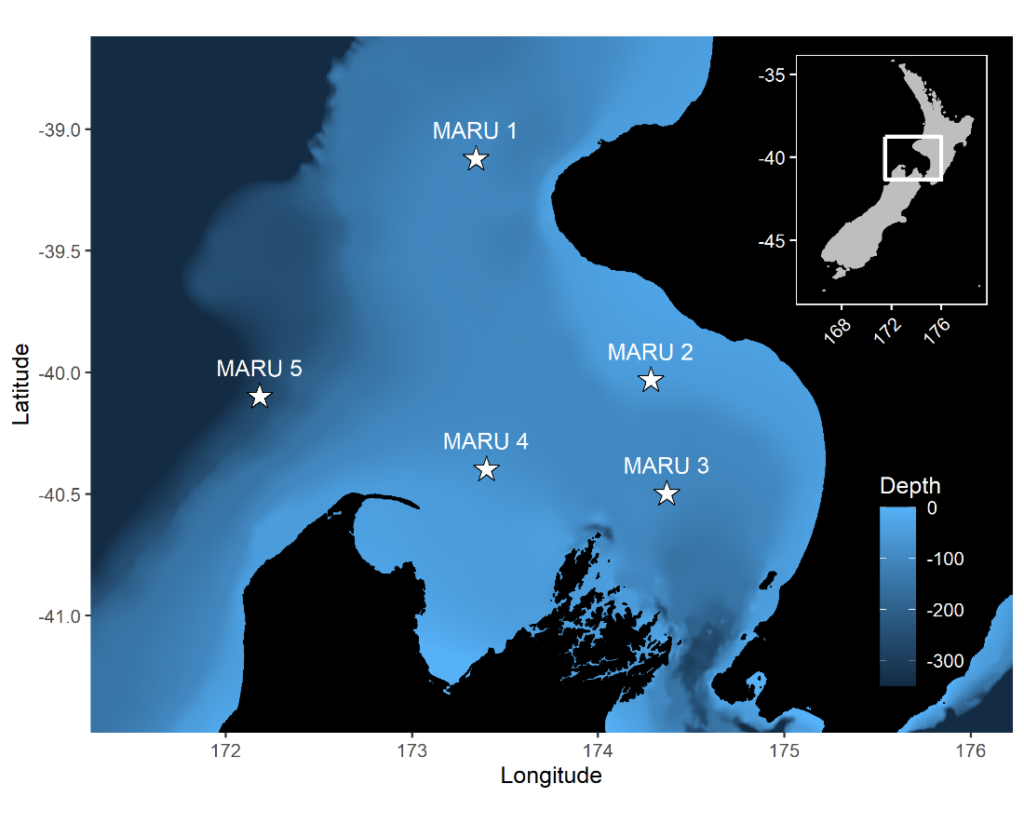

But in the meantime, I have taken this year as an opportunity to work with the GEMM lab, while continuing to enjoy the marvels of New Caledonia, a French overseas territory where I have lived for more than 6 years now. Among the animals that I get to approach and observe regularly in the coral reef lagoons that surround the island, the dugong (Dugon dugon) is perhaps the most emblematic and intriguing. This marine mammal is listed as vulnerable in the IUCN Red list of threatened species and has been the focus of important research and conservation efforts in New Caledonia over the last two decades1–3. During my previous post-doctoral position at the French Institute of Research for Sustainable Development, I contributed to some recent research involving satellite tracking of dugongs in the region. This work has led to a publication, now in review4, and will be the topic of my oral presentation at the 7th International Bio-Logging Science Symposium hosted in Hawaii in a couple weeks.

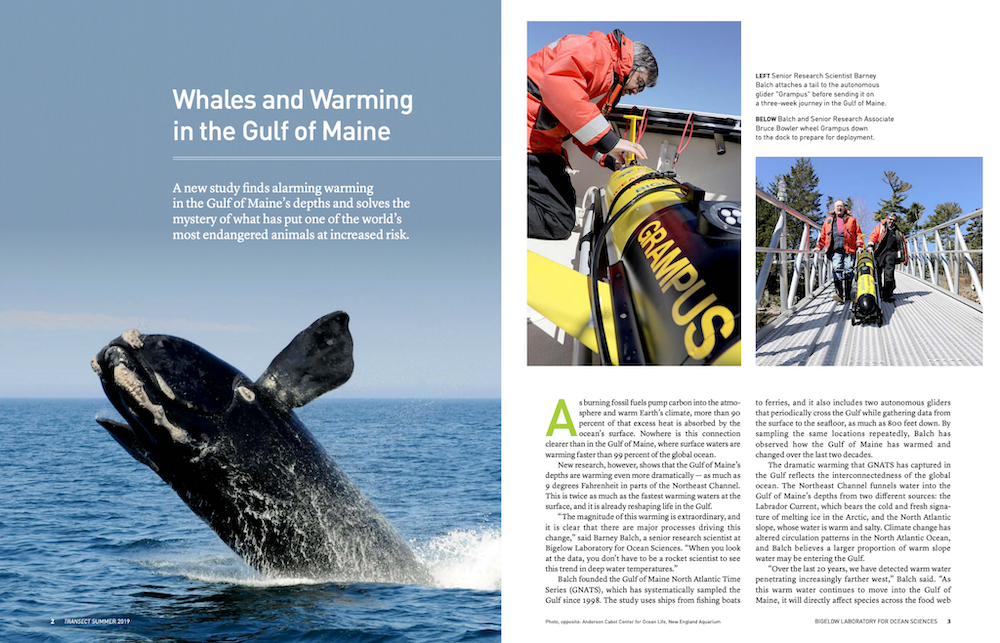

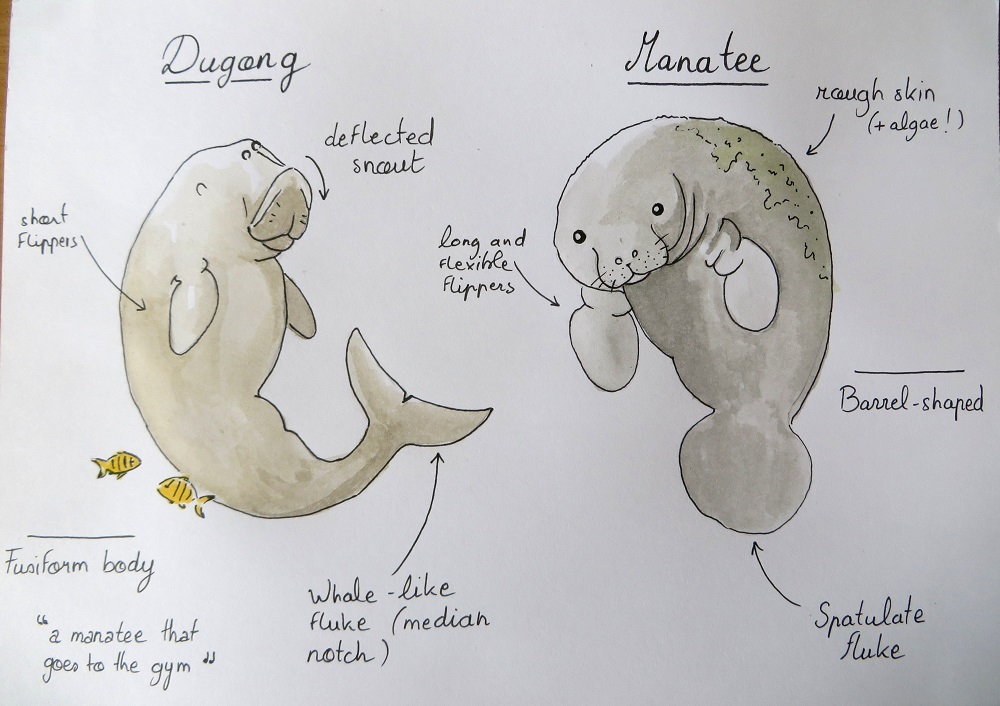

While I was analyzing dugong satellite tracks, writing this paper with my colleagues and preparing for the symposium, I learned a lot about these strange “sea cows”. Dugongs belong to the Sirenian marine mammal order, just like manatees (West Indian, Amazonian and West African species), which they are often mistaken for (watch out: Google Images will misleadingly suggest hundreds of manatee pictures if you make a “dugong” keyword search). The physiology and anatomy of dugongs is actually quite different from that of manatees (Figure 1). They also live in a different part of the world as they are broadly distributed in the Indo-Pacific coastal and island waters. Dugongs form separate populations, some of which are very isolated and at high risk of extirpation. They are found in 37 different countries, with Australia being home to the largest populations by far (exceeding 70,000 individuals5).

Sea cow or sea elephant?

Through the tree of evolution, the dugong and manatee’s closest relative is not the one you would think… other marine mammals like cetaceans or pinnipeds. Indeed, molecular genetic analyses have placed the Sirenians in the Afrotheria Superorder of mammals. Therefore, it appears that dugongs are more closely related to elephant and golden moles than to whales and dolphins!

As a memory aid to help remember this ancient origin, we may notice that both elephants and dugongs have tusks. Mature male and female dugongs have erupted tusks, although the females’ only erupt rarely and at a very old age. Interestingly, tusks are used by scientists to determine age. Analyses of growth layers in bisected dugong tusks have revealed that dugongs are long-lived, with a maximum longevity record of 73 years (estimated from a female individual found in Western Australia5).

An (almost) vegetarian marine mammal

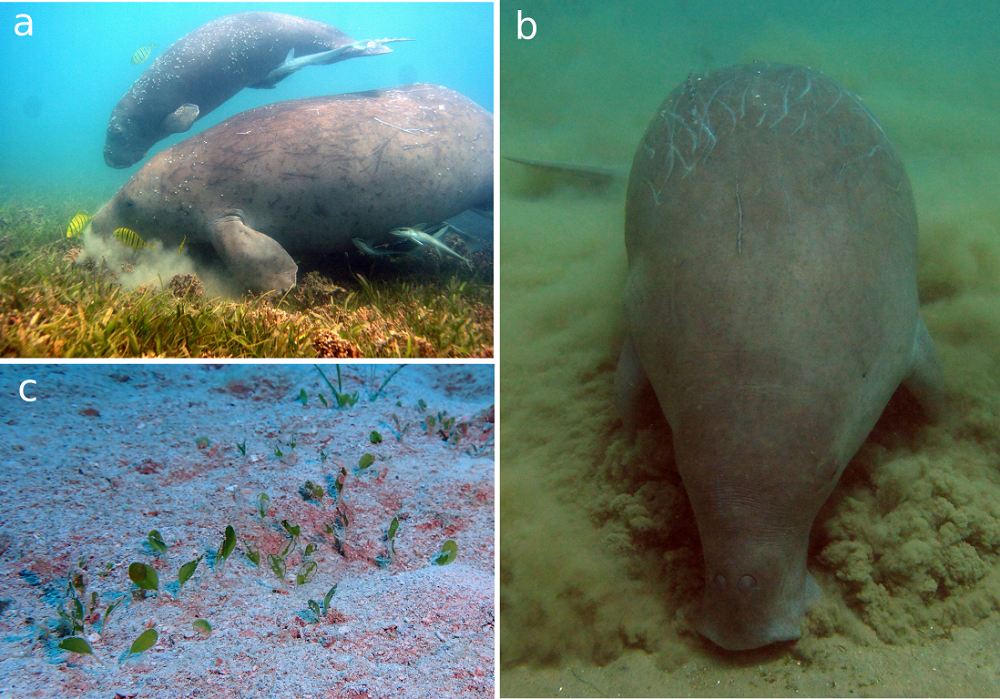

Dugongs and manatees are the only predominantly herbivorous aquatic mammals. Given that manatees use both marine and fresh water ecosystems they tend to have a broader diet, eating many kinds of submerged, floating or emergent algae and seagrass (even bank growth!). On the other hand, dugongs are a strictly marine species and primarily feed on seagrass, which may look very similar to seaweeds, but are in fact marine flowering plants. Seagrass tend to form underwater shallow meadows that are among the most productive ecosystems in the world6. In fact, dugong grazing influences the biomass, species composition and nutritional quality of seagrass meadows7,8. Just like we take care of our gardens, dugongs regulate seagrass ecosystems. But there is more. Recent research conducted in the Great Barrier Reef indicates that seagrass seeds that have been digested by dugongs germinate at a faster rate9. As well as playing a role in dispersal10, it appears that dugongs are pooping seeds with enhanced germination potential, hence participating to seagrass meadow resilience.

Unlike manatees, dugongs cannot feed over the whole water column and are strictly bottom feeders. They use their deflected snout (Figure 1) to search the seabed for their favorite food (Figure 2). The feeding trails left by dugongs in dense seagrass meadows are easily detectable from above, just like the sediment clouds that they generate when searching muddy bottoms. Although seagrass is undoubtedly the main component of the dugong’s diet, they may incidentally (or not) ingest algae and invertebrates5.

A legendary animal

The etymology for the word Sirenian comes from the mermaids, or “sirens” of the Greek mythology. These aquatic creatures with the upper body of a female human would sing to lure sailors towards the shore… and towards a certain death. The morphology of dugongs and manatees shares some resemblance with mermaids, at least enough for desperate and lonely sailors to think so!

In addition to having a scientific name rooted in legends, dugongs are also important to contemporary human cultures. In tropical islands and coastal communities, marine megafauna species such as dugongs are considered heritage, due to the strong bond that their people have forged with the ocean5. Dugongs may play an important cultural role because they can be part of the socio-symbolic organization of societies, associated with the imaginary world, or simply because they are seen as companions of the sea, which people frequently encounter. For New Caledonia’s indigenous people, the Kanaks, dugongs can be totem to tribes. Like other large marine species (whales, sharks), the dugong is also considered as an embodiment of ancestors11.

Dugongs have been hunted throughout their range since prehistoric times. Archaeological excavations such as those conducted on the island of Akab in the United Arab Emirates12, indicate that dugong hunting played a role in ancient rituals, in addition to providing a large quantity of meat. The cultural value of dugongs is recognized by multiple countries, which have therefore authorized indigenous dugong hunting, sometimes under quotas. For instance, in Australia, dugongs may be legally hunted by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (Figure 3) under section 211 of the Native Title Act 1993.

In New Caledonia, the dugong has been protected since 1962 and its hunting is only authorized in one province, with a dispensation for traditional Kanak celebrations13. However, in view of the critical situation in which the New Caledonian dugong population finds itself, estimated at around 700 individuals in 2008-201214, no hunting exemptions have been issued since 2004.

What future for dugongs?

Despite legislations to forbid dugong meat consumption outside specific traditional permits, poaching persists, in New Caledonia and in many of the “low-income” countries that are home to dugongs. As climate change and demography intensifies risks to food security, scientists and stakeholders fear for dugongs. Moreover, dugongs entirely rely on seagrass ecosystems that are also disappearing at an alarming rate (7% per year6) as a result of coastal development, pollution and overfishing.

Can we preserve dugongs in regions of high climate vulnerability and where people still have low levels of access to basic needs? Can dugongs play the role of “umbrellas” for the conservation of the ecosystem they live in? I do not have the answer to these questions but I certainly believe that people’s well-being and environmental conservation are tightly intertwined. I hope that rising transdisciplinary approaches such as those supported by the “One Health” framework will help reconnect human populations to their environment, and achieve the goal of optimal health for everyone, humans and animals.

References

1. Garrigue, C., Patenaude, N. & Marsh, H. Distribution and abundance of the dugong in New Caledonia, southwest Pacific. Mar. Mammal Sci. 24, 81–90 (2008).

2. Cleguer, C., Grech, A., Garrigue, C. & Marsh, H. Spatial mismatch between marine protected areas and dugongs in New Caledonia. Biol. Conserv. 184, 154–162 (2015).

3. Cleguer, C., Garrigue, C. & Marsh, H. Dugong (Dugong dugon) movements and habitat use in a coral reef lagoonal ecosystem. Endanger. Species Res. 43, 167–181 (2020).

4. Derville, S., Cleguer, C. & Garrigue, C. Ecoregional and temporal dynamics of dugong habitat use in a complex coral reef lagoon ecosystem. Sci. Rep. (In review)

5. Marsh, H., O’Shea, T. J. & Reynolds, J. E. I. Ecology and conservation of the Sirenia: dugongs and manatees, Vol 18. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2011).

6. Unsworth, R. K. F. & Cullen-Unsworth, L. C. Seagrass meadows. Curr. Biol. 27, R443–R445 (2017).

7. Aragones, L. V., Lawler, I. R., Foley, W. J. & Marsh, H. Dugong grazing and turtle cropping: Grazing optimization in tropical seagrass systems? Oecologia 149, 635–647 (2006).

8. Preen, A. Impacts of dugong foraging on seagrass habitats: observational and experimental evidence for cultivation grazing. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 124, 201–213 (1995).

9. Tol, S. J., Jarvis, J. C., York, P. H., Congdon, B. C. & Coles, R. G. Mutualistic relationships in marine angiosperms: Enhanced germination of seeds by mega-herbivores. Biotropica (2021) doi:10.1111/btp.13001.

10. Tol, S. J. et al. Long distance biotic dispersal of tropical seagrass seeds by marine mega-herbivores. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–8 (2017).

11. Dupont, A. Évaluation de la place du dugong dans la société néo-calédonienne. (Mémoire Master. Encadré par L. Gardes (Agence des Aires Marines Protégées) et C. Sabinot (IRD), 2015).

12. Méry, S., Charpentier, V., Auxiette, G. & Pelle, E. A dugong bone mound: The Neolithic ritual site on Akab in Umm al-Quwain, United Arab Emirates. Antiquity 83, 696–708 (2009).

13. Leblic, I. Vivre de la mer, vivre de la terre… en pays kanak. Savoirs et techniques des pêcheurs kanak du sud de la Nouvelle-Calédonie. (Société des Océanistes, 2008).

14. Hagihara, R. et al. Compensating for geographic variation in detection probability with water depth improves abundance estimates of coastal marine megafauna. PLoS One 13, e0191476 (2018).