By Solène Derville, Postdoc, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Science, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

Filling the gaps

Reports of whale entanglements have been on the rise over the last decade on the US West Coast, with Dungeness crab fishing gear implicated in many cases (Feist et al., 2021; Samhouri et al., 2021; Santora et al., 2020). State agencies are responsible for managing this environmental issue that has implications both for the endangered whale sub-populations that are subject to entanglements, and for the fishing activities, which play an important social, cultural, and economic role for coastal communities. In Oregon, the Oregon Whale Entanglement Working Group (today the Oregon Entanglement Advisory Committee, facilitated by ODFW – Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife) formed in 2017, tasked with developing options to reduce entanglement risk. The group members composed of managers, researchers and fishermen identified that a lack of information and understanding of whale distribution in Oregon waters was a significant knowledge gap of high priority.

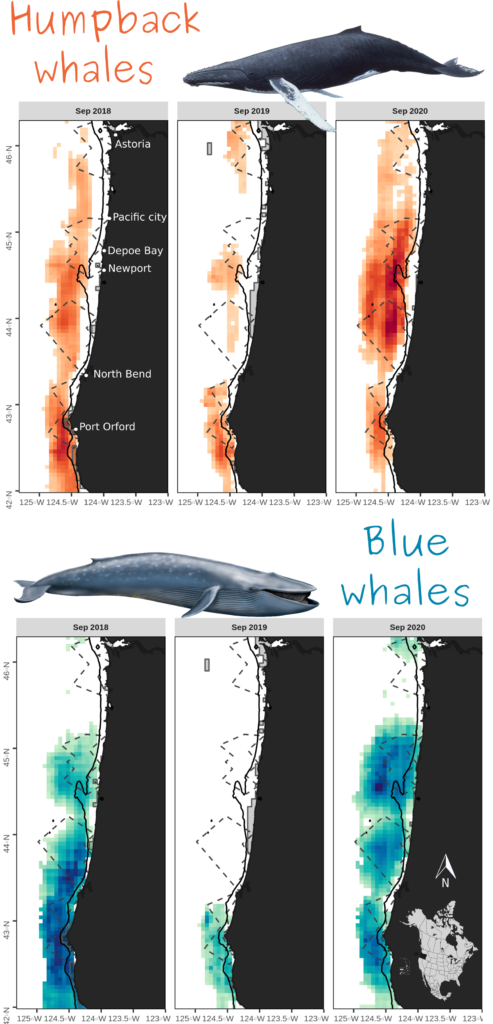

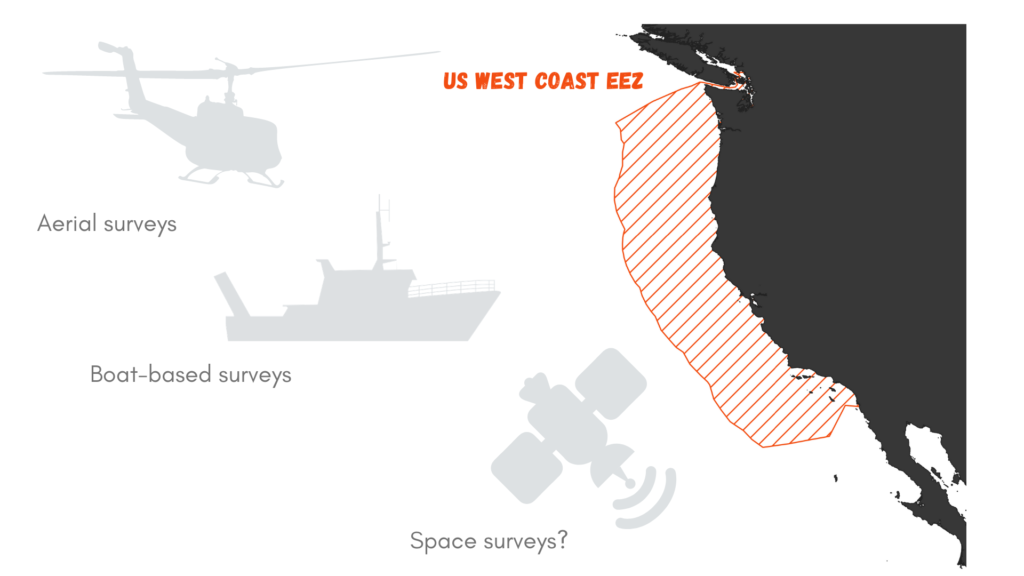

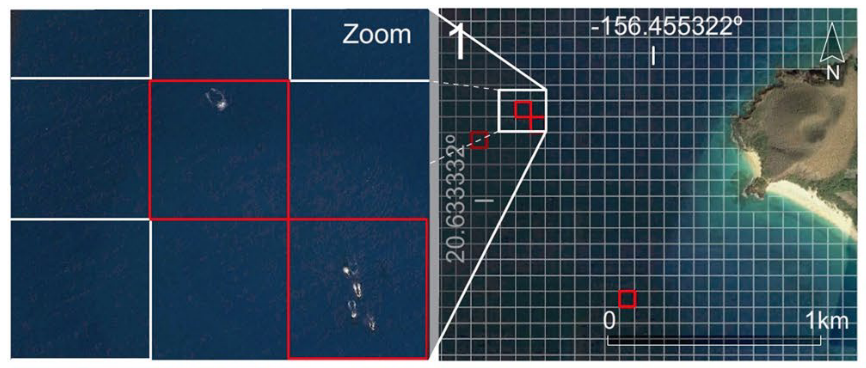

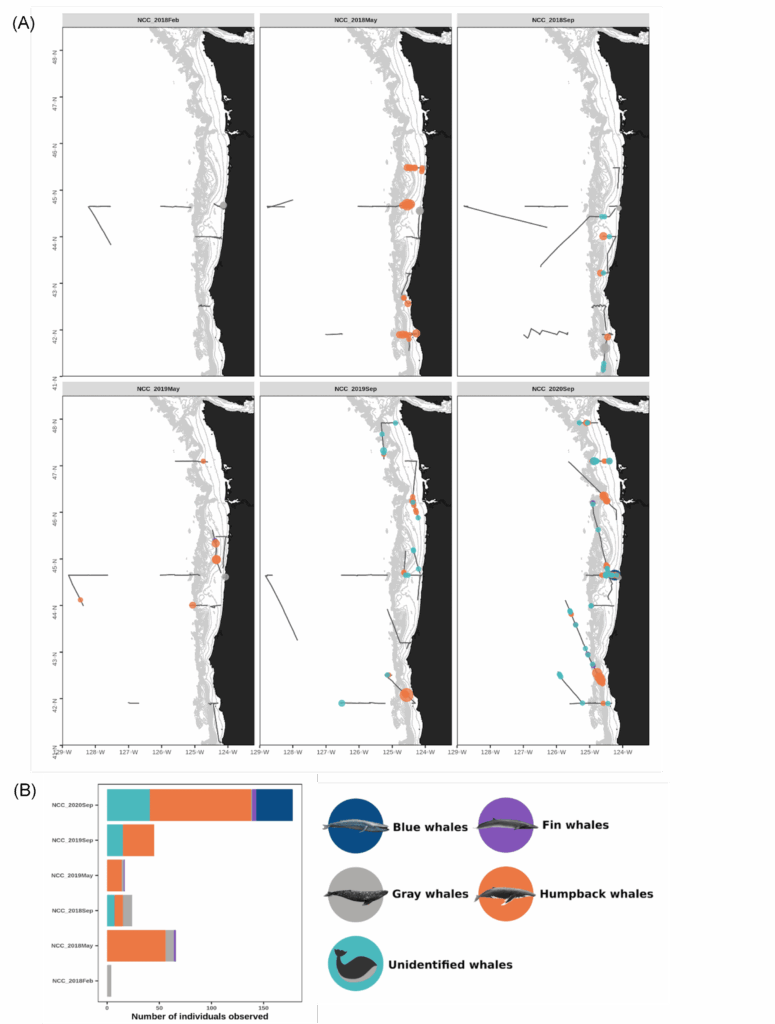

In response, the GEMM Lab and its collaborators at ODFW developed the OPAL project (Overlap Predictions About Large whales, phase 1: 2018-2022). The first phase of the project (phase 1) was developed to 1) model and predict large whale distribution off the coast of Oregon in relation to dynamic environmental conditions, and 2) assess overlap with commercial crab fishing gear to inform conservation efforts. Although this first phase was extended up to June as a result of COVID, it is now coming to an end. As a postdoc in the GEMM Lab, I have been the main analyst working on this project. The habitat use models that I generated from several years of aerial and boat-based surveys provide improved knowledge about where and when rorqual whales (combining blue, humpback and fin) are most abundant (Derville et al., 2022). Moreover, we are about to publish an analysis of overlap between whale predicted densities and commercial Dungeness crab fishing effort. This analysis of co-occurrence over 10 years shows distinct spatio-temporal patterns in relation to climatic fluctuations affecting the northern California Current System (Derville et al., In review).

Although we are quite satisfied with the outputs of these four years of research, this is not the end of it! Project OPAL continues into a second phase (2022-2025; supported by NOAA Section 6 funding), during which models will be improved and refined via incorporation of new survey data (helicopter and boat-based) as well as prey data (krill and fish distribution). PhD student Rachel Kaplan is a key contributor to this research, and I will do my best to keep assisting her in this journey in the years to come.

Announcing SLATE!

As this newly acquired knowledge leads to potentially new management measures in Oregon, it becomes essential for managers to evaluate their impacts on the entanglement issue. But how do we know exactly how many entanglements occur during any year within Oregon waters? Is recording reports of entanglements or signs of entanglements in stranded whales enough? The simple answer is no. Entanglements are notoriously under-detected and under-reported (Tackaberry et al., 2022). Over the US West Coast, entanglements are also relatively rare events that can easily go unnoticed in the immensity of the ocean. Moreover, entangled large whales are often able to carry the fishing gear for some time away from the initial gearset location, which makes it hard to locate the origin of the gear causing problems (van der Hoop et al., 2017).

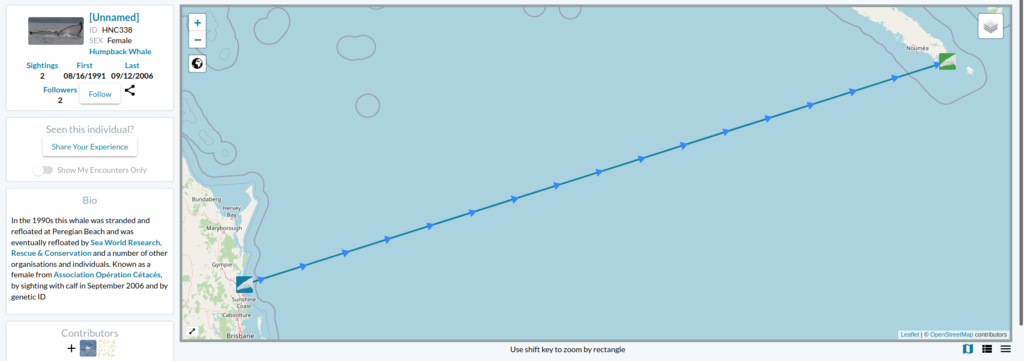

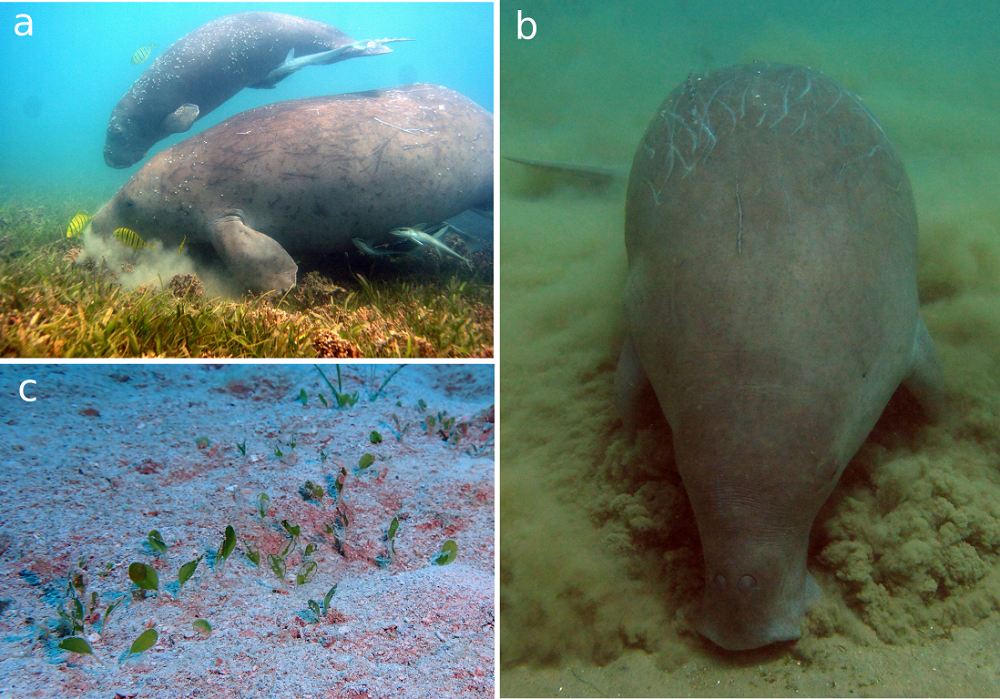

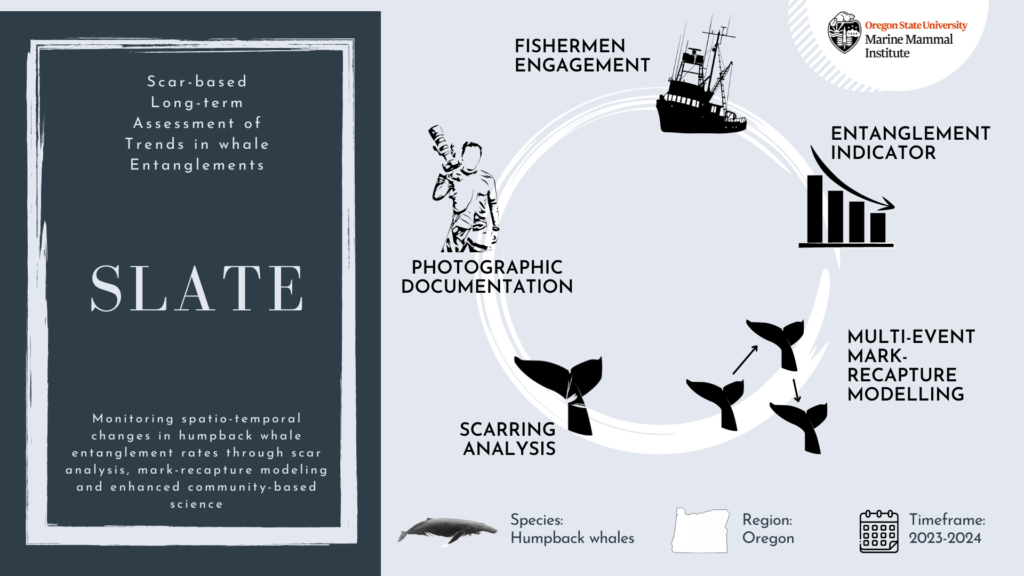

Our approach to the challenge of assessing humpback whale entanglement rates in Oregon waters is to use scar analysis. Our new “SLATE” (Scar-based Long-term Assessment of Trends in whale Entanglements, Figure 1) project will be using scar-based methods as a proxy to detect unobserved entanglement events (e.g., Basran et al., 2019; Bradford et al., 2009; George et al., 2017; Knowlton et al., 2012; Robbins, 2012). Indeed, this approach has been effective to detect potential interactions with fishing gear at a much higher frequency than entanglement reports in the Atlantic Ocean (e.g., only 10% of entanglements of humpback whales in the Gulf of Maine were estimated to be reported; Robbins, 2012). We will be examining hundreds of photographs of humpback whales observed in Oregon waters to try to detect wrapping scars and notches that result from entanglement events. Based on this scar pattern, we will assign each whale a qualitative probability of prior entanglement (i.e., uncertain, low, high). We will specifically be looking at the caudal peduncle (the attachment point of the whale’s fluke, see Figure 2) following a methodology developed in the Gulf of Maine by Robbins & Mattila, (2001).

Data please?

While this approach is to-date the most applicable way to assess otherwise undetected entanglements, it is sometimes limited by sample size. Although we plan to collect more photos in the field in summer 2023 and 2024, this long-term analysis of scarring patterns would not be possible without the contribution of the Cascadia Research Collective (CRC) led by John Calambokidis. The CRC humpback whale catalogue will be crucial to assessing entanglement rates at the individual level over the last decade.

Moreover, as we have been contemplating the task ahead of us, we realized that the data collected through traditional scientific surveys might not be sufficient to achieve our goal. We need the help of the people who live off the ocean and encounter whales on a day-to-day basis: fishermen. That is why we decided to solicit interested fishermen to take photographs of whales while at sea. Starting this year, we will work with at least three self-selected fishermen who are interested in supporting this program and collecting data to support the research efforts. Participants will be provided a stipend, equipped with a high-quality camera, and trained to photograph whales while following National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) guidelines.

And here come the statistics…

If we have some of my previous blogs (e.g., May 2022, June 2018), you know that I usually participate in projects that have a significant statistical modeling component. As part of the SLATE project, I will be trying out some new approaches that I never had the opportunity to work with before, which makes me feels both super excited and slightly apprehensive!

First, I will analyze humpback whale scarring at the population level. That means I will be using all available photos of whales in Oregon waters without considering individual identification, and I will model the probability of entanglement scars in relation to space and time. This model will help us answer questions such as: did whales have a higher chance of becoming entangled in certain years over others? Did whales observed in a certain zone in Oregon waters have a higher risk of getting entangled?

Second, I will analyze humpback whale scarring at the individual level. This time, we will only use encounters of a selected number of individuals that have a long recapture history, meaning that they were photo-identified and resighted several times throughout the last decade. Using a genetic database produced by the Cetacean Conservation and Genomic Laboratory (CCGL, Marine Mammal Institute), we will also be able to tell to which “Distinct Population Segment” (DPS) some of these individual whales belong. Down the line, this is an important piece of information because humpback whale DPS do not breed in the same areas, and these groups have different levels of population health. Then, we will use what is known as a “multi-event mark-recapture model” to estimate the probability of entanglement as a function of time and spatial residency or DPS assignment, while accounting for detection probability and survival.

Through these analyses, our goal is to produce a single indicator to help managers assess the effects of mandatory or voluntary changes in Oregon fishing practices. In the end, we hope that these models will provide a measurable and robust way of monitoring whale entanglements in fishing gear off the coast of Oregon.

References

Basran, C. J., Bertulli, C. G., Cecchetti, A., Rasmussen, M. H., Whittaker, M., & Robbins, J. (2019). First estimates of entanglement rate of humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae observed in coastal Icelandic waters. Endangered Species Research, 38(February), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.3354/ESR00936

Bradford, A. L., Weller, D. W., Ivashchenko, Y. v., Burdin, A. M., & Brownell, R. L. (2009). Anthropogenic scarring of western gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus). Marine Mammal Science, 25(1), 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2008.00253.x

Derville, S., Barlow, D. R., Hayslip, C. E., & Torres, L. G. (2022). Seasonal, Annual, and Decadal Distribution of Three Rorqual Whale Species Relative to Dynamic Ocean Conditions Off Oregon, USA. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.868566

Derville, S., Buell, T., Corbett, K., Hayslip, C., & Torres, L. G. (n.d.). Exposure of whales to entanglement risk in Dungeness crab fish-ing gear in Oregon, USA, reveals distinctive spatio-temporal and climatic patterns. Biological Conservation.

Feist, B. E., Samhouri, J. F., Forney, K. A., & Saez, L. E. (2021). Footprints of fixed-gear fisheries in relation to rising whale entanglements on the U.S. West Coast. Fisheries Management and Ecology, 28(3), 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/fme.12478

George, J. C., Sheffield, G., Reed, D. J., Tudor, B., Stimmelmayr, R., Person, B. T., Sformo, T., & Suydam, R. (2017). Frequency of injuries from line entanglements, killer whales, and ship strikes on bering-chukchi-beaufort seas bowhead whales. Arctic, 70(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic4631

Knowlton, A. R., Hamilton, P. K., Marx, M. K., Pettis, H. M., & Kraus, S. D. (2012). Monitoring North Atlantic right whale Eubalaena glacialis entanglement rates: A 30 yr retrospective. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 466(Kraus 1990), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps09923

Robbins, J. (2012). Scar-Based Inference Into Gulf of Maine Humpback Whale Entanglement : 2010 (Issue January). Report to the Northeast Fisheries Science Center National Marine Fisheries Service, EA133F09CN0253 Item 0003AB, Task 3.

Robbins, J., & Mattila, D. K. (2001). Monitoring entanglements of humpback whales ( Megaptera novaeangliae ) in the Gulf of Maine on the basis of caudal peduncle scarring. SC/53/NAH25. Report to the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission, 14, 1–12. http://www.ccbaymonitor.org/pdf/scarring.pdf

Samhouri, J. F., Feist, B. E., Fisher, M. C., Liu, O., Woodman, S. M., Abrahms, B., Forney, K. A., Hazen, E. L., Lawson, D., Redfern, J., & Saez, L. E. (2021). Marine heatwave challenges solutions to human-wildlife conflict. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 288, 20211607. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.1607

Santora, J. A., Mantua, N. J., Schroeder, I. D., Field, J. C., Hazen, E. L., Bograd, S. J., Sydeman, W. J., Wells, B. K., Calambokidis, J., Saez, L., Lawson, D., & Forney, K. A. (2020). Habitat compression and ecosystem shifts as potential links between marine heatwave and record whale entanglements. Nature Communications, 11, 536. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-14215-w

Tackaberry, J., Dobson, E., Flynn, K., Cheeseman, T., Calambokidis, J., & Wade, P. R. (2022). Low Resighting Rate of Entangled Humpback Whales Within the California , Oregon , and Washington Region Based on Photo-Identification and Long-Term Life History Data. Frontiers in Marine Science, 8(January), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.779448

van der Hoop, J., Corkeron, P., & Moore, M. (2017). Entanglement is a costly life-history stage in large whales. Ecology and Evolution, 7(1), 92–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.2615