By Solène Derville, Postdoc, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Science, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

I wrote my last blogpost in the midst of winter and feeling overwhelmed as I was trying to fly to the US at the peak of the omicron pandemic… Since then, morale has improved exponentially. I have spent two months in the company of my delightful GEMM lab friends, nerding over statistics, sharing scientific conversations, drinking (good!) beer and enjoying the company of this great group of people. During that stay, I was able to focus on my OPAL project more than I have ever been able to, as I set myself the goal of not getting distracted by anything else during my stay in Newport.

The only one distraction that I do not regret is a post I read one morning on the Cetal Fauna Facebook page, a group of cetacean experts and lovers who share news, opinions, photos… anything cetacean related! Someone was posting a photo of a humpback whale stranded in the 1990s’ on Coolum beach, on the east coast of Australia, which is known as a major humpback whale migratory corridor. The story said that (probably with considerable effort) the whale was refloated by many different individuals and organizations present at the beach on that day, specifically Sea World Research, Rescue & Conservation.

I felt very touched by this story and the photo that illustrated it (Figure 1). Seeing all these people come together in this risky operation to save this sea giant is quite something. And the fact that they succeeded was even more impressive! Indeed, baleen whales strand less commonly than toothed whales but their chances of survival when they do so are minimal. In addition to the actual potential damages that might have caused the whale to strand in the first place (entanglements, collisions, diseases etc.), the beaching itself is likely to hurt the animal in a permanent way as their body collapses under their own weight usually causing a cardiovascular failure (e.g., Fernández et al., 2005). The rescue of baleen whales is also simply impaired by the sheer size and weight of these animals. Compared to smaller toothed whales such as pilot whales and false killer whales that happen to strand quite frequently over some coastlines, baleen whales are almost impossible to move off the beach and getting close to them when beached can be very dangerous for responders. For these reasons, I found very few reports and publications mentioning successful rescues of beached baleen whales (e.g., Priddel and Wheeler, 1997; Neves et al., 2020).

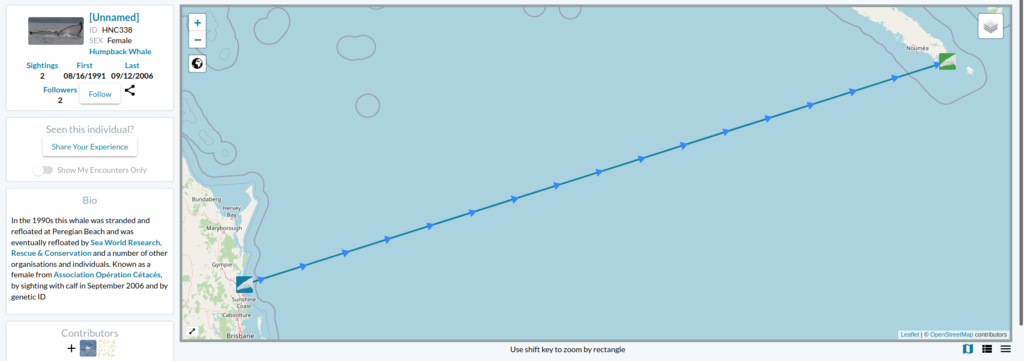

Now the story gets even better… the following day I received an email from Ted Cheeseman, director and co-founder of Happywhale, a collaborative citizen science tool to share and match photographes of cetaceans (initially only humpback whales but has extended to other species) to recognize individuals based on the unique patterns of the their fluke or dorsal fin. The fluke of the whale stranded in Australia in 1991 had one and only match within the Happywhale immense dataset… and that match was to a whale seen in New Caledonia (Figure 2). “HNC338” was the one!

Since I conducted my PhD on humpback whale spatial ecology in New Caledonia, I have continued working on a number of topics along with my former PhD supervisor, Dr Claire Garrigue, in New Caledonia. Although I do not remember each and every whale from her catalogue (composed of more than 1600 humpback whales as of today), I do love a good “whale tale” and I was eager to know who this HNC338 was. I quickly looked into Claire’s humpback whale database and sure enough I found it there: encountered at the end of the 2006 breeding season on September 12th, at a position of 22°26.283’S and 167°01.991’E and followed for an hour. Field notes reported a shy animal that kept the boat at a distance. But most of all, HNC338 was genetically identified as a female and was accompanied by a calf during that season! The calf was particularly big, as expected at this time of the season. What an inspiring thing to think that this whale, stranded in 1996, was resighted 10 years later in a neighboring breeding ground, apparently healthy and raising a calf of her own.

As genetic paternity analysis have been conducted on many New Caledonia calf biopsy samples as part of the Sexy Singing project conducted with our colleagues from St Andrews University in Scotland, we might be able to identify the calf’s father in this breeding stock. Thanks to the great amount of data shared and collected through Happywhale, we are discovering more and more about whale migratory patterns and behavior. It might as well be that this calf’s father was one of those whales that seem to roam over several different breeding grounds (New Caledonia and East Australia). This story is far from finished…

From the people who pulled this whale back into the water in 1996, to the scientists and cetacean enthusiasts who shared their data and whale photos online, this story once again shows us that hope lies in cooperation! Happywhale was only created in 2015 but since then it has brought together the general public and the scientists to contribute over 465,000 photos allowing the identification of 75,000 different individuals around the globe. In New Caledonia, in Oregon and elsewhere, I hope that these collective initiatives grow more and more in the future, to the benefit of biodiversity and people.

Did you enjoy this blog? Want to learn more about marine life, research, and conservation? Subscribe to our blog and get weekly updates and more! Just add your name into the subscribe box on the left panel.

References

Cheeseman, T., Southerland, K., Park, J., Olio, M., Flynn, K., Calambokidis, J., et al. (2021). Advanced image recognition: a fully automated, high-accuracy photo-identification matching system for humpback whales. Mamm. Biol. doi:10.1007/s42991-021-00180-9.

Fernández, A., Edwards, J. F., Rodríguez, F., Espinosa De Los Monteros, A., Herráez, P., Castro, P., et al. (2005). “Gas and fat embolic syndrome” involving a mass stranding of beaked whales (Family Ziphiidae) exposed to anthropogenic sonar signals. Vet. Pathol. 42, 446–457. doi:10.1354/vp.42-4-446.

Neves, M. C., Neto, H. G., Cypriano-Souza, A. L., da Silva, B. M. G., de Souza, S. P., Marcondes, M. C. C., et al. (2020). Humpback whale (megaptera novaeangliae) resighted eight years after stranding. Aquat. Mamm. 46, 483–487. doi:10.1578/AM.46.5.2020.483.

Priddel, D., and Wheeler, R. (1997). Rescue of a Bryde’s whale Balaenoptera edeni entrapped in the Manning River, New South Wales: Unmitigated success or unwarranted intervention? Aust. Zool. 30, 261–271. doi:10.7882/AZ.1997.002.