Clara Bird, PhD Candidate, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

As you may remember, last year’s field season was a remarkable summer for our team. We were pleasantly surprised to find an increased number of whales in our study area compared to previous years and were even more excited that many of them were old friends. As we started this field season, we were all curious to know if this year would be a repeat. And it’s my pleasure to report that this season was even better!

We started the season with an exciting day (6 known whales! see Lisa’s blog) and the excitement (and whales) just kept coming. This season we saw 71 individual whales across 215 sightings! Of those 71, 44 were whales we saw last year, and 10 were new to our catalog, meaning that we saw 17 whales this season that we had not seen in at least two years! There is something extra special about seeing a whale we have not seen in a while because it means that they are still alive, and the sighting gives us valuable data to continue studying health and survival. Another cool note is that 7 of our 12 new whales from last year came back this year, indicating recruitment to our study region.

Included in that group of 7 whales are the two calves from last year! Again, indicating good recruitment of new whales to our study area. We saw both Lunita and Manta (previously nick-named ‘Roly-poly’) throughout this season and we were always happy to see them back in our area and feeding on their own.

We had an especially remarkable encounter with Lunita at the end of this season when we found this whale surface feeding on porcelain crab larvae (video 1)! This is a behavior that we rarely observe, and we’ve never seen a juvenile whale use this behavior before, inspiring questions around how Lunita knew how to perform this behavior.

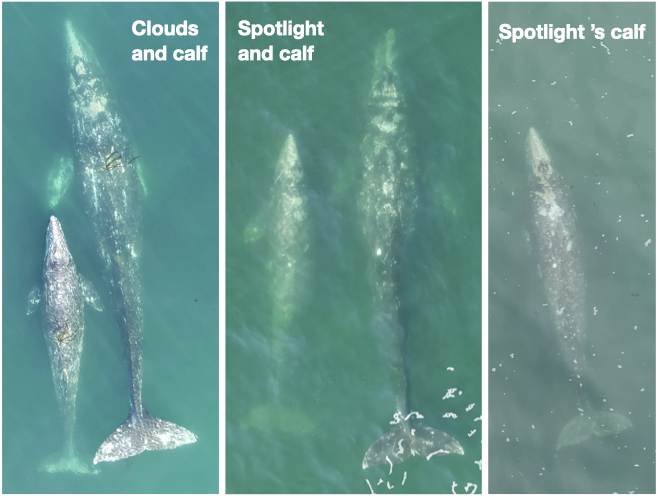

Not only did we resight our one-year-old friends, but we found two new calves born to well-known mature females (Clouds and Spotlight). We had previously documented Clouds with a calf (Cheetah) in 2016 so it was exciting to see her with a new calf and to meet Cheetah’s sibling! Cheetah has become one of our regulars so we’re curious to see if this new calf joins the regular crew as well. We’re also hoping that Spotlight’s calf will stick around; and we’re optimistic since we observed it feeding alone later in the season.

Of course, 71 whales means heaps of data! We spent 226 hours on the water, conducted 132 drone flights (a record!), and collected 61 fecal samples! Those 132 flights were over 64 individual whales, with Casper and Pacman tying for “best whale to fly over” with 10 flights each. We collected 61 fecal samples from 26 individual whales with a three-way tie for “best pooper” between Hummingbird, Scarlett, and Zorro with 6 fecal samples each. And we continued to collect valuable prey and habitat data through 80 GoPro drops and 79 zooplankton net tows.

And if you were about to ask, “but what about tagging?!”, fear not! We continued our suction cup tagging effort with a successful window in July where we were joined by collaborators John Calambokidis from Cascadia Research Collective and Dave Cade from Hopkins Marine Station and deployed four suction-cup tags.

It’s hard to believe all the work we’ve accomplished in the past five months, and I continue to be honored and proud to be on this incredible team. But as this season has come to a close, I have found myself reflecting on something else. Learning. Over the past several years we have learned so much about not only these whales in our study system but about how to conduct field work. And while learning is continuous, this season in particular has felt like an exciting time for both. In the past year our group has published work showing that we can detect pregnancy in gray whales using fecal samples and drone imagery (Fernandez Ajó et al., 2023), that PCFG gray whales are shorter and smaller than ENP whales (Bierlich et al., 2023), and that gray whales are consuming high levels of microplastics (Torres et al., 2023). We also have several manuscripts in review focused on our behavior work from drones and tags. While this information does not directly affect our field work, it does mean that while we’re observing these whales live, we better understand what we’re observing and we can come up with more specific, in-depth questions based on this foundation of knowledge that we’re building. I have enjoyed seeing our questions evolve each year based on our increasing knowledge and I know that our collaborative, inquisitive chats on the boat will only continue inspiring more exciting research.

On top of our gray whale knowledge, we have also learned so much about field work. When I think back to the early days compared to now, there is a stark difference in our knowledge and our confidence. We do a lot on our little boat! And so many steps that we once relied on written lists to remember to do are now just engrained in our minds and bodies. From loading the boat, to setting up at the dock, to the go pro drops, fecal collections, drone operations, photo taking, and photo ID, our team has become quite the well-oiled machine. We were also given the opportunity to reflect on everything we’ve learned over the past years when it was our turn to train our new team member, Nat! Nat is a new PhD student in the GEMM lab who is joining team GRANITE. Teaching her all the ins and outs of our fieldwork really emphasized how much we ourselves have learned.

On a personal note, this was my third season as a drone pilot, and honestly, I was pleasantly surprised by my experience this season. Since I started piloting, I have experienced pretty intense nerves every time I’ve flown the drone. From stress dreams, to mild nausea, and an elevated heart rate, flying the drone was something that I didn’t necessarily look forward to. Don’t get me wrong – it’s incredibly valuable data and a privilege to watch the whales from a bird’s eye view in real time. But the responsibility of collecting good data, while keeping the drone and my team members safe was something that I felt viscerally. And while I gained confidence with every flight, the nerves were still as present as ever and I was starting to accept that I would never be totally comfortable as a pilot. Until this season, when the nerves finally cleared, and piloting became as innate as all the other field work components. While there are still some stressful moments, the nerves don’t come roaring back. I have finally gone through enough stressful situations to not be fazed by new ones. And while I am fully aware that this is just how learning works, I write this reflection as a reminder to myself and anyone going through the process of learning any new skill to push through that fear. Remember there can be a disconnect between the time when you know how to do something well, or well-enough, and the time when you feel comfortable doing it. I am just as proud of myself for persevering as I am of the team for collecting so much incredible data. And as I look ahead to my next scary challenge (finishing my PhD!), this is a feeling that I am trying to hold on to.

Stay tuned for updates from team GRANITE!

Did you enjoy this blog? Want to learn more about marine life, research, and conservation? Subscribe to our blog and get a weekly alert when we make a new post! Just add your name into the subscribe box below!

References

Bierlich, K. C., Kane, A., Hildebrand, L., Bird, C. N., Fernandez Ajo, A., Stewart, J. D., Hewitt, J., Hildebrand, I., Sumich, J., & Torres, L. G. (2023). Downsized: Gray whales using an alternative foraging ground have smaller morphology. Biology Letters, 19(8), 20230043. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2023.0043

Fernandez Ajó, A., Pirotta, E., Bierlich, K. C., Hildebrand, L., Bird, C. N., Hunt, K. E., Buck, C. L., New, L., Dillon, D., & Torres, L. G. (2023). Assessment of a non-invasive approach to pregnancy diagnosis in gray whales through drone-based photogrammetry and faecal hormone analysis. Royal Society Open Science, 10(7), 230452. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.230452

Torres, L. G., Brander, S. M., Parker, J. I., Bloom, E. M., Norman, R., Van Brocklin, J. E., Lasdin, K. S., & Hildebrand, L. (2023). Zoop to poop: Assessment of microparticle loads in gray whale zooplankton prey and fecal matter reveal high daily consumption rates. Frontiers in Marine Science, 10. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2023.1201078