Marc Rams i Rios, PhD Student, Oregon State University Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

When I moved to Oregon to begin my PhD, I pictured long days on the water watching gray whales feed and travel along the coast. That does happen, and it is as incredible as I imagined. But I have learned that studying cetaceans is about much more than observing whales. It is also about people: how cultures – past and present – perceive these animals and share space with them.

In addition to marine mammals, I have always loved history and geography. Now, as I start my work with the GRANITE Project in the GEMM Lab, I find myself thinking about how these relationships between humans and whales unfold across time and space. In this post, I want to share a few examples of how whales have shaped human traditions for hundreds, even thousands of years, across societies that have never crossed. Then I will discuss how our research fits into this larger picture of human–cetacean connections.

Our journey begins in India, where the Ganges River dolphin inhabits a river that millions of people consider sacred. Its presence has long been linked to the health of the river, giving the species spiritual and cultural significance. Over the past century, the river’s ecological integrity has declined due to pollution, altered flow, and habitat disturbances, and this has caused the dolphin population to diminish1, 2. Conservation efforts that improve water quality, restore natural flow, and reduce disturbances not only help the dolphin recover but also protect the river and the human communities that rely on it1, 2. In this way, cultural reverence for the dolphin drives conservation measures that benefit both people and ecosystems1, 2.

From there we move to Aotearoa, New Zealand, where Māori tradition speaks of tohorā, or whales, as guardians and ancestors3. They appear in ancestral stories as guides and protectors, and whale strandings have historically brought communities together in collective response. The Māori principles of kaitiakitanga, or guardianship, continue to shape marine conservation decisions today, guiding policies that integrate ecological and cultural values4. Here, whales are not seen as resources. They are part of a living genealogy that binds people to the sea and the life it sustains. In fact, team members of the SAPPHIRE project in the GEMM lab frequently engage with multiple iwi (Māori tribes) across Aotearoa through hui (meetings) where knowledge, stories, and culture are shared about blue whales and their ecosystem.

Traveling nearly to the antipodes, we arrive on the Atlantic coast of Brazil, in the town of Laguna, where an extraordinary partnership has endured for centuries. Artisanal fishers work alongside bottlenose dolphins, who drive schools of fish toward the shore and signal the right moment to cast the nets5, 6, 7. This cooperation benefits both species, and the knowledge behind it is passed down through generations of humans and dolphins through observation and shared practice5, 6, 7. It is a powerful example of how species can learn from one another, creating connections that challenge the idea of humans and wildlife as competitors and showing the potential for collaboration across species5, 6, 7. The LABIRINTO Lab in MMI has studied this interspecific relationship for decades, helping us learn about the patterns and endurance of these cultures.

At the top of the Americas, in the Arctic, Inuit communities have hunted bowhead whales for thousands of years. These hunts are not only a source of food but also form the foundation of cultural identity and social life8. Knowledge of the ice, weather, and whale behavior is passed down through generations, and the hunt itself is embedded in ceremonies and practices that sustain the community8. Today, these traditions continue under strict quotas set through international agreements, carefully balancing cultural continuity with conservation9. The MMBEL lab in MMI studies the communication and ecology of bowhead whales to support the survival of this iconic species and the culture of Inuit people.

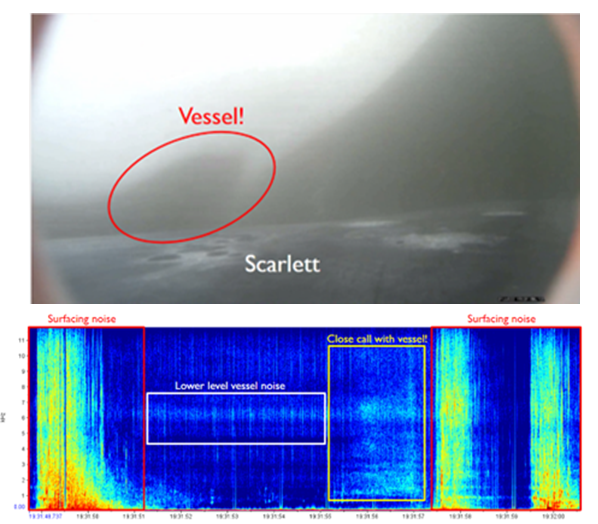

Finally, our journey brings us to Oregon, where gray whales feed along a coastline rich with reefs, kelp beds, and sandy bottoms. These waters support a variety of human activities, from commercial fishing to recreation, creating risks such as entanglement, vessel strikes, and disturbance10, 11. Even well-intentioned actions like whale watching can cause harm if not carefully managed12, 13. Around the world, many communities have shifted from whaling to whale watching, transforming former hunting grounds into tourism destinations. While this is a positive change, it still requires monitoring. Noise can stress whales, boats can disrupt their behavior, and too much interaction can alter natural feeding and social patterns12, 13. In Oregon, research on gray whale habitat use and feeding home ranges helps inform management and conservation14.

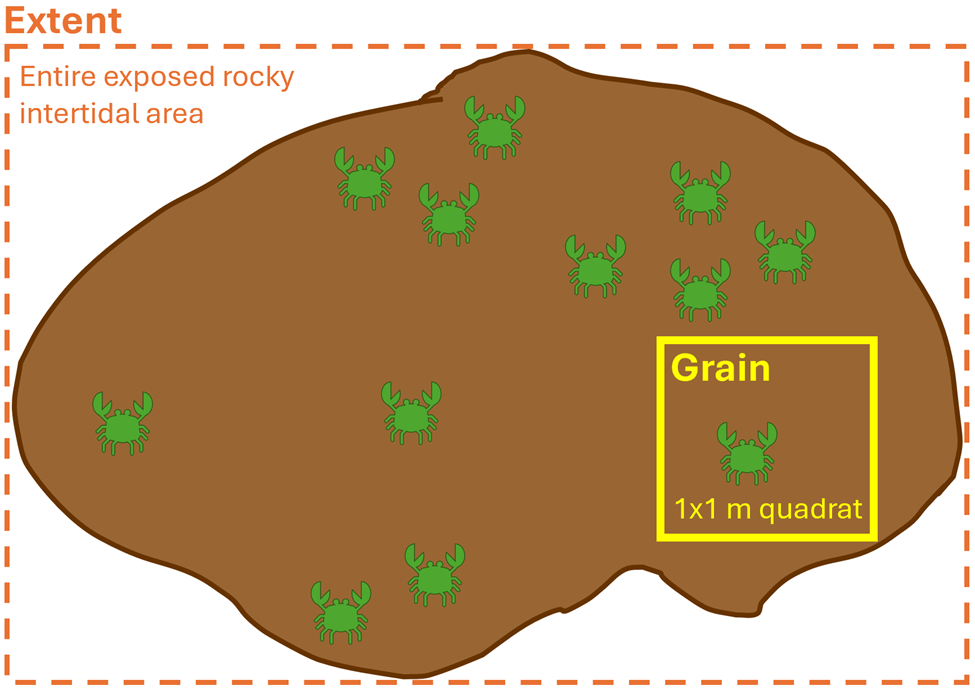

This is where project GRANITE, Gray whale Response to Ambient Noise Informed by Technology and Ecology, comes in15. The project studies how whales respond to human activities by using drones to monitor health and behavior, photo-ID to track individuals, prey mapping to understand feeding choices, and acoustic recorders to capture the soundscape15, 16, 17. Equally important is collaborating directly with fishers and resource managers to reduce risks and develop solutions that benefit both whales and people. Healthy whale populations support communities too, through ecotourism, cultural continuity, education, and the ecological services whales provide. Conservation is reciprocal: caring for whales strengthens the ocean systems that sustain us all.

The tools and techniques developed by GRANITE, including drones, acoustic monitoring, and prey mapping, are not limited to Oregon. They can be applied globally, contributing to the protection of cetaceans in diverse habitats15. In this way, Oregon becomes more than the final stop on our tour. It is a place where centuries of human–whale relationships, lessons from around the world, and modern science converge. These examples across the world remind us that conservation is about more than preventing harm. It is about fostering a future where humans and whales thrive together, as they have shared the ocean for millennia.

Did you enjoy this blog? Want to learn more about marine life, research, and conservation? Subscribe to our blog and get a monthly message when we post a new blog. Just add your name and email into the subscribe box below.

References

1 Sinha, R. K., & Kannan, K. (2014). Ganges river dolphin: An overview of biology, ecology, and conservation status in India. AMBIO, 43(8), 1029–1046. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-014-0534-7

2 Braulik, G., Atkore, V., Khan, M. S., & Malla, S. (2021). Review of scientific knowledge of the Ganges river dolphin. WWF. https://riverdolphins.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Ganges-River-dolphin-Scientific-Knowledge-Review-July2021.pdf

3 Taonga, N. Z. M. for C. and H. T. M. (n.d.). Whales in Māori tradition. Teara.govt.nz. https://teara.govt.nz/en/te-whanau-puha-whales/page-1

4 McAllister, T., Hikuroa, D., & Macinnis‑Ng, C. (2023). Connecting science to Indigenous knowledge: Kaitiakitanga, conservation, and resource management. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 47(1), 3521. https://doi.org/10.20417/nzjecol.47.3521

5 Simões‑Lopes, P. C., Fabián, M. E., & Menegheti, J. O. (1998). Dolphin interactions with the mullet artisanal fishing on southern Brazil: A qualitative and quantitative approach. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, 15(3), 709–726. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81751998000300008

6 Daura Jorge, F. G., Cantor, M., Ingram, S. N., Lusseau, D., & Simões Lopes, P. C. (2012). The structure of a bottlenose dolphin society is coupled to a unique foraging cooperation with artisanal fishermen. Biology Letters, 8(5), 702–705. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2012.0174

7 Cantor, M., Farine, D. R., & Daura‑Jorge, F. G. (2023). Foraging synchrony drives resilience in human–dolphin mutualism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(6), e2207739120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2207739120

8 Jensen, A. M. (2012). The material culture of Iñupiat whaling: An ethnographic and ethnohistorical perspective. Arctic Anthropology, 49(2), 143–161. https://doi.org/10.1353/arc.2012.0020

9 Description of the USA Aboriginal Subsistence Hunt: Alaska. (n.d.). Iwc.int. https://iwc.int/management-and-conservation/whaling/aboriginal/usa/alaska

10 Derville, S., Buell, T. V., Corbett, K. C., Hayslip, C., & Torres, L. G. (2023). Exposure of whales to entanglement risk in Dungeness crab fishing gear in Oregon, USA. Biological Conservation, 281, 109989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2023.109989

11 Silber, G. K., Weller, D. W., Reeves, R. R., Adams, J. D., & Moore, T. J. (2021). Co‑occurrence of gray whales and vessel traffic in the North Pacific Ocean. Endangered Species Research, 44, 177–201. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01093

12 Sullivan, F. A., & Torres, L. G. (2018). Assessment of vessel disturbance to gray whales to inform sustainable ecotourism. Journal of Wildlife Management, 82(5), 896–905. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.21462

13 Sprogis, K. R., Videsen, S., & Madsen, P. T. (2020). Vessel noise levels drive behavioural responses of humpback whales with implications for whale‑watching. eLife, 9, e56760. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.56760

14 Lagerquist, B. A., Palacios, D. M., Winsor, M. H., Irvine, L. M., Follett, T. M., & Mate, B. R. (2019). Feeding home ranges of Pacific Coast Feeding Group gray whales. Journal of Wildlife Management, 83(4), 925–937. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.21642

15 GRANITE: Gray whale Response to Ambient Noise Informed by Technology and Ecology | Marine Mammal Institute | Oregon State University. (n.d.). Mmi.oregonstate.edu. https://mmi.oregonstate.edu/gemm-lab/granite-gray-whale-response-ambient-noise-informed-technology-ecology

16 Pirotta, E., Bierlich, K. C., New, L., Bird, C. N., Fernandez Ajó, A., Hildebrand, L., Buck, C. L., Hunt, K. E., Calambokidis, J., & Torres, L. G. (2025). Body size, nutritional state and endocrine state are associated with calving probability in a long‑lived marine species. Journal of Animal Ecology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.70068

17 Bierlich, K. C., Kane, A., Hildebrand, L., Bird, C. N., Fernandez Ajó, A., Stewart, J. D., Hewitt, J., Hildebrand, I., Sumich, J., & Torres, L. G. (2023). Downsized: Gray whales using an alternative foraging ground have smaller morphology. Biology Letters, 19(7), 20230043. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2023.0043