Clara Bird, PhD Candidate, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

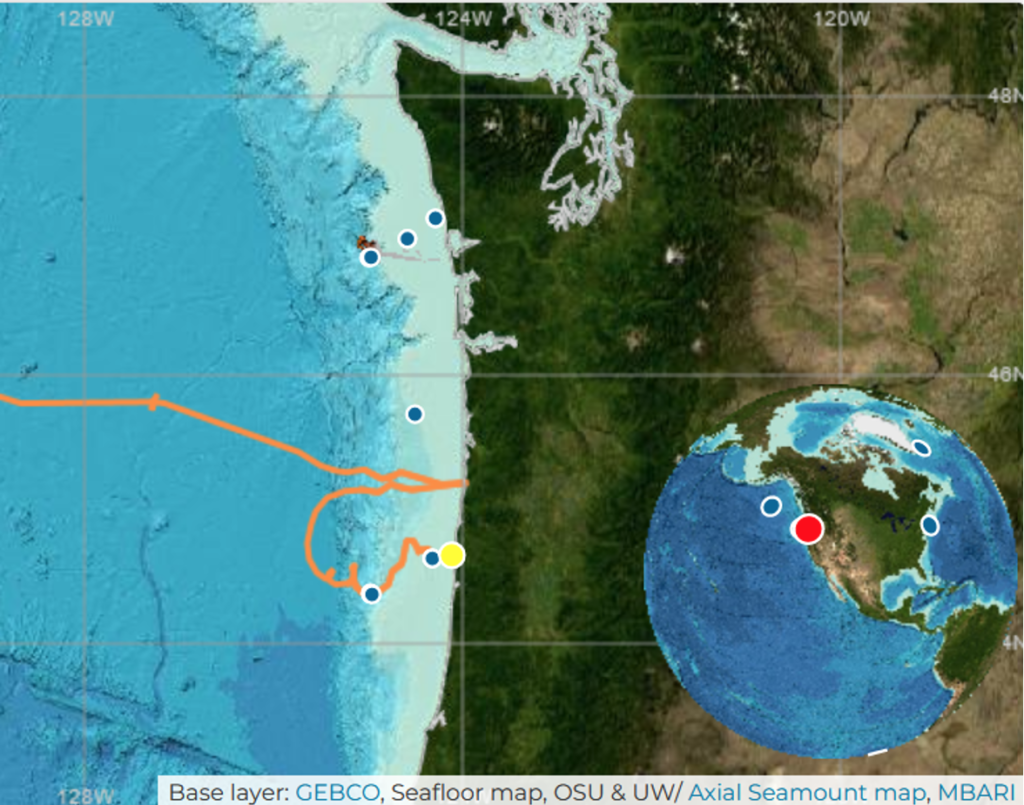

It’s hard to believe that it’s already been four and half months since we started the field season (check out Lisa’s blog for a recap of where we began), but as of this weekend the GRANITE project’s 8th field season has officially ended! As the gray whales wrap up their foraging season and start heading south for the winter, it’s time for us to put our gear into storage, settle into a new academic year, and start processing the data we spent so much time collecting.

The field season can be quite an intense time (40 days equaling over 255 hours on the water!), so we often don’t take a moment to reflect until the end. But this season has been nothing short of remarkable. As you may remember from past blogs, the past couple years (2020-21) have been a bit concerning, with lower whale numbers than previously observed. Since many of us started working on the project during this time, most of us were expecting another similar season. But we were wrong in the best way. From the very first day, we saw more whales than in previous years and we identified whales from our catalog that we hadn’t seen in several years.

We identified friends – old and new!

This season we had 224 sightings of 63 individual whales. Of those 63, 51 were whales from our catalog (meaning we have seen them in a previous season). Of these 51 known whales, we only saw 20 of them last year! This observation brings up interesting questions such as, where did most of these whales forage last year? Why did they return to this area this year? And, the classic end of season question, what’s going to happen next year?

We also identified 12 whales that were not in our catalog, making them new to the GEMM lab. Two of our new whales are extra exciting because they are not just new to us but new to the population; we saw two calves this year! We were fortunate enough to observe two mom-calf pairs in July. One pair was of a “new” mom in our catalog and her calf. We nicknamed this calf “Roly-poly” because when we found this mom-calf pair, we recorded some incredible drone footage of “roly-poly” continuously performing body rolls while their mom was feeding nearby (video 1).

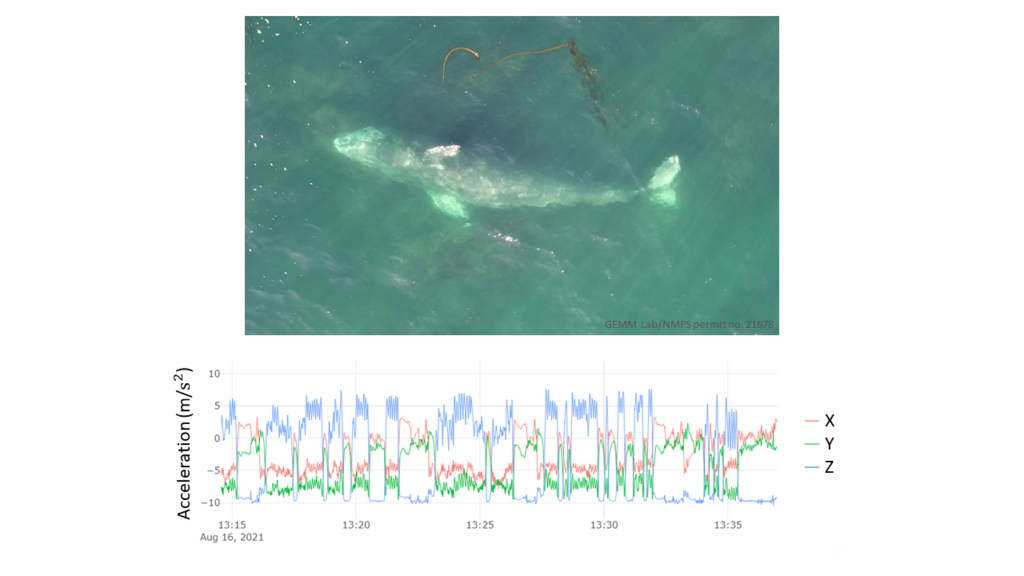

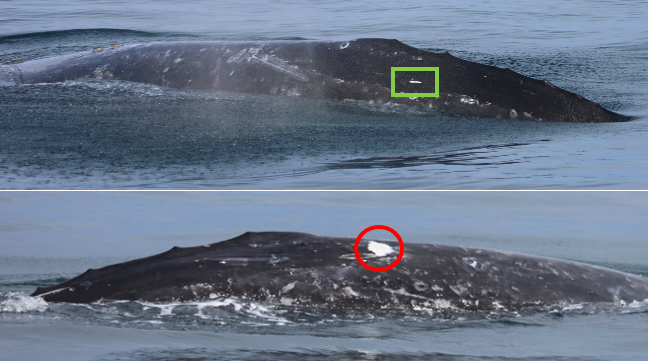

The other pair includes a known GEMM lab whale, Luna, and her calf (currently nicknamed “Lunita”). We recently found “Lunita” feeding on their own in early October (Image 2), meaning that they are now independent from its mom (for more on mom-calf behavior check out Celest’s recent blog). We’ll definitely be on the lookout for Roly-Poly and Lunita next year!

We flew, we scooped, we collected heaps of data!

From our previous blogs you probably know that in addition to photo-ID images, our other two most important forms of data collection are drone flights (for body condition and behavior data) and fecal samples (for hormone analysis). And this season was a success for both!

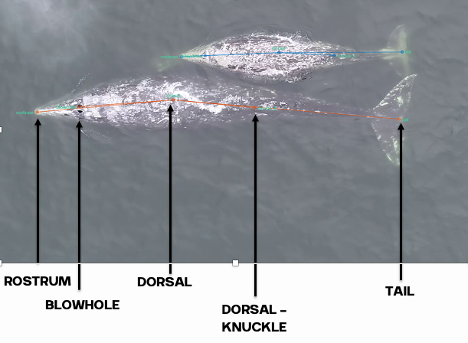

We conducted 124 flights over 49 individual whales. The star of these flights was a local favorite Scarlett who we flew over 18 different times. These repeat samples are crucial data for us because we use them to gain insight into how an individual’s body condition changes throughout the season. We also recorded loads of behavior data, collecting footage of different foraging tactics like headstanding, side-swimming, and surfacing feeding on porcelain crab larvae (video 2)!

We also collected 61 fecal samples from 26 individual whales (Image 3). The stars of that dataset were Soléand Peak who tied with 7 samples each. These hard-earned samples provide invaluable insight into the physiology and stress levels of these individuals and are a crucial dataset for the project.

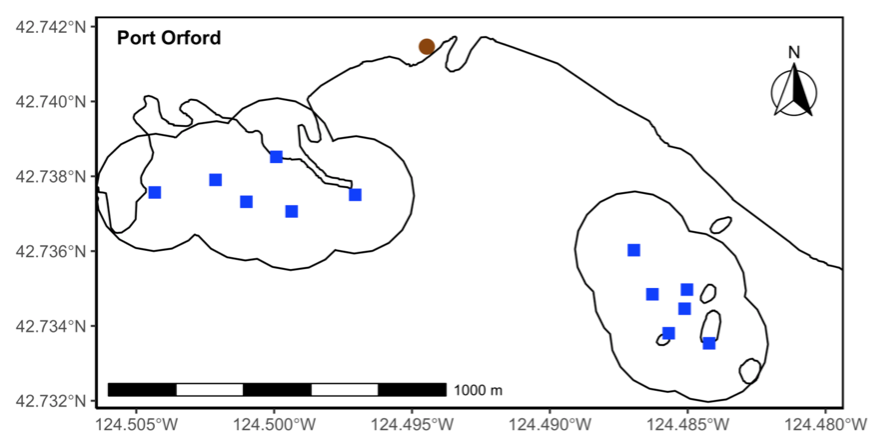

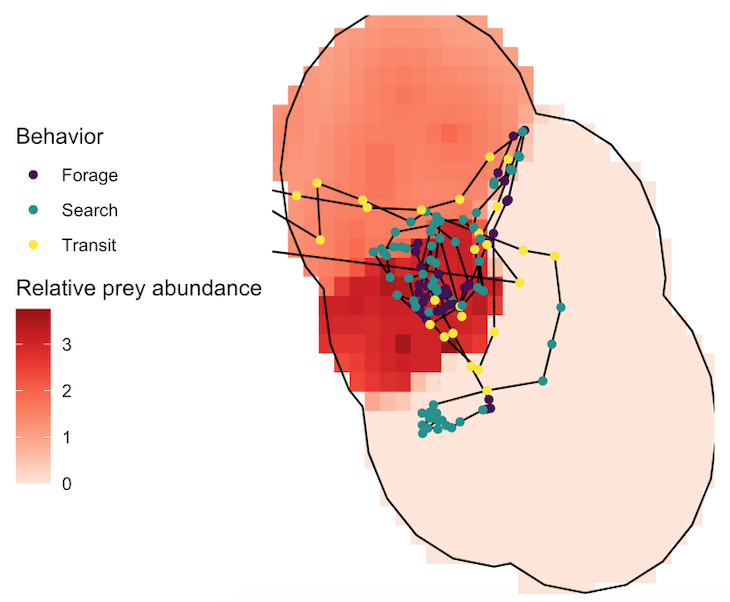

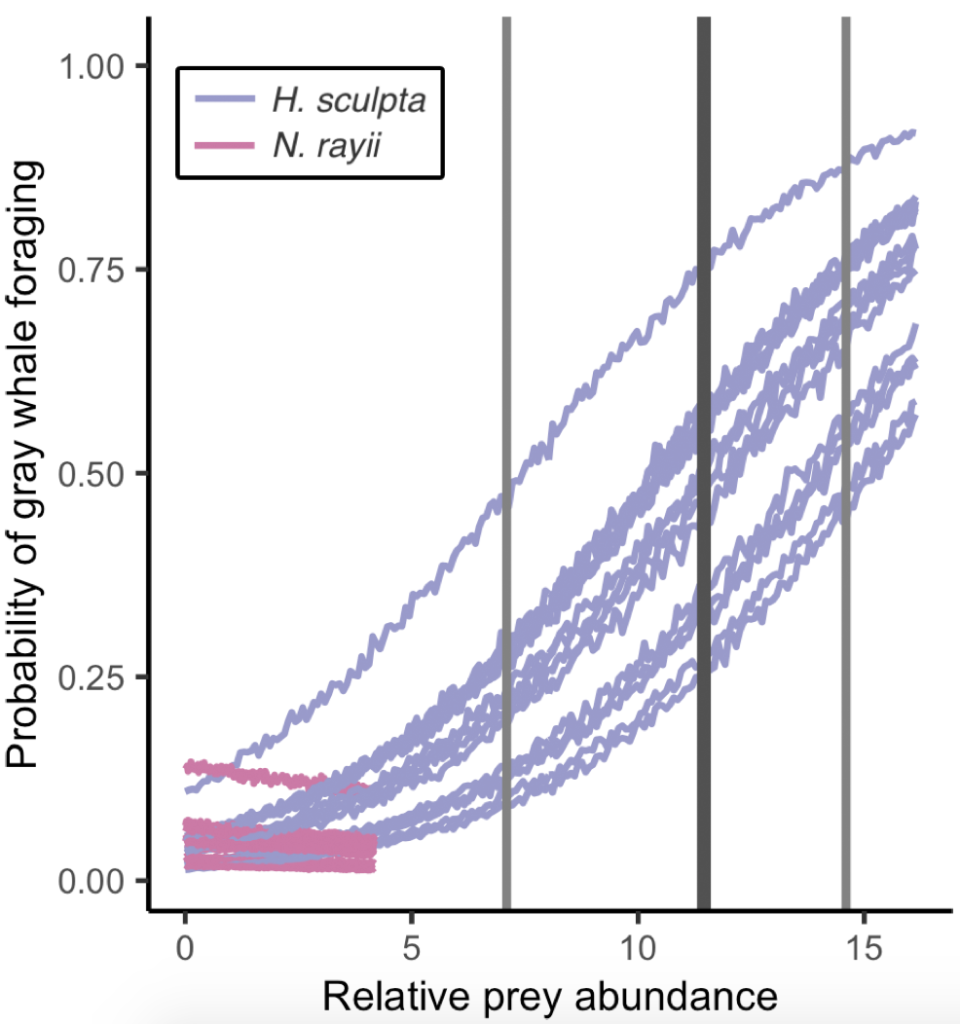

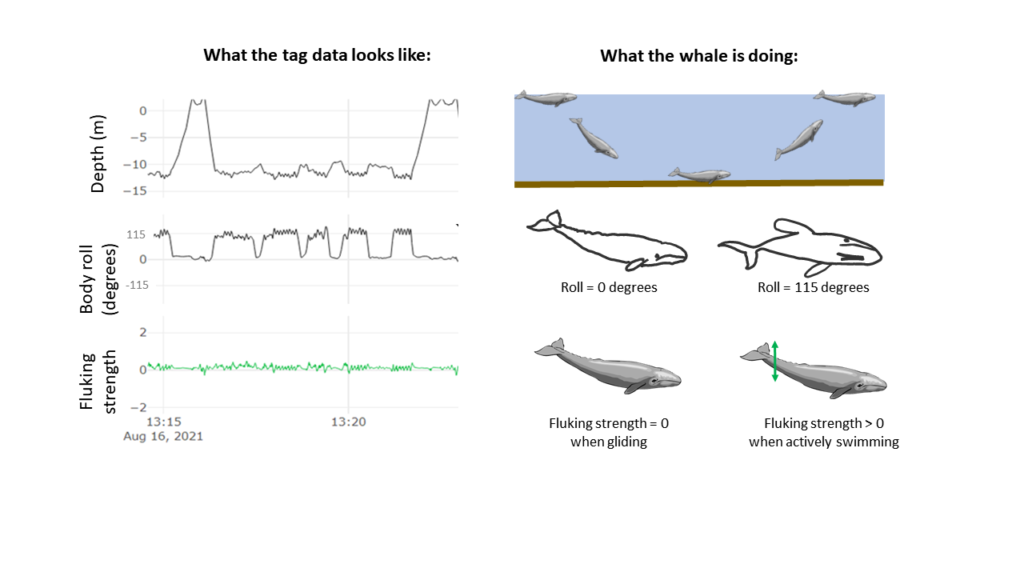

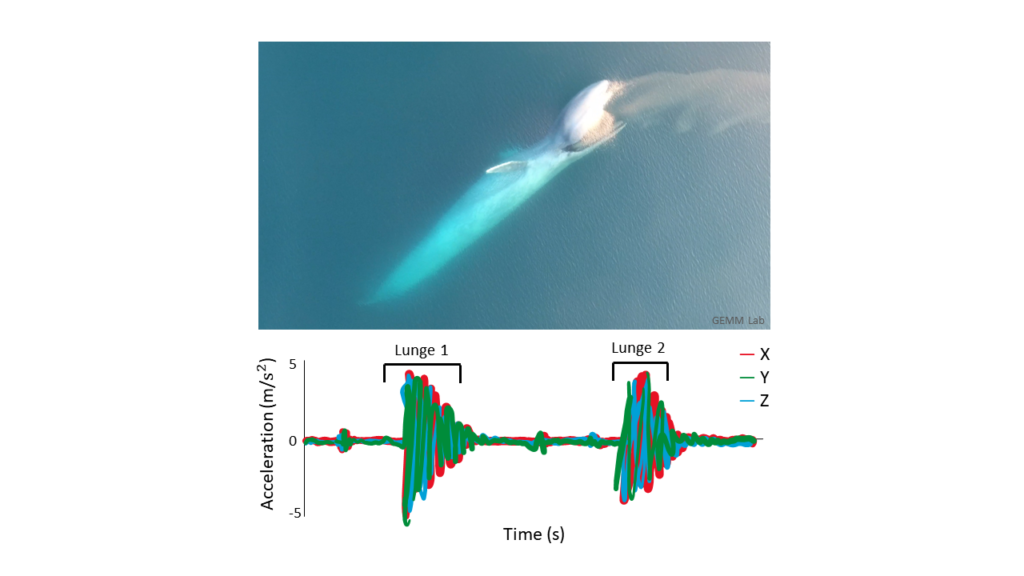

On top of all that amazing data collection we also collected acoustic data with our hydrophones, prey data from net tows, and biologging data from our tagging efforts. Our hydrophones were in the water all summer recording the sounds that the whales are exposed to, and they were successfully recovered just a few weeks ago (Image 4)! We also conducted 69 net tows to sample the prey near where the whales were feeding and identify which prey the whales might be eating (Image 5). Lastly, we had two very successful tagging weeks during which we deployed (and recovered!) a total of 9 tags, which collected over 30 hours of data (Image 6; check out Kate’s blog for more on that).

Final thoughts

All in all, it’s been an incredible season. We’ve seen the return of old friends, collected lots of awesome data, and had some record-breaking days (28 whales in one day!). As we look toward the analysis phase of the year, we’re excited to dig into our eight-year dataset and work to understand what might explain the increase in whales this year.

To end on a personal note, looking through photos to put in this blog was the loveliest trip down memory lane (even though it only ended a few days ago) – I am so honored and proud to be a part of this team. The work we do is hard; we spend long hours on a small boat together and it can be a bit grueling at times. But, when I think back on this season, my first thoughts are not of the times I felt exhausted or grumpy, but of all the joy we felt together. From the incredible whale encounters to the revitalizing snacks to the off-key sing alongs, there is no other team I would rather do this work with, and I so look forward to seeing what next season brings. Stay tuned for more updates from team GRANITE!

Did you enjoy this blog? Want to learn more about marine life, research, and conservation? Subscribe to our blog and get a weekly alert when we make a new post! Just add your name into the subscribe box below!