Dr. Clara Bird, Postdoctoral Scholar, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences, GEMM Lab & LABIRINTO

Cycles can be found everywhere in nature and our lives. From tides and seasons to school years and art projects, we’re constantly experiencing cycles of varying scales. Spring on the Oregon coast brings several important cyclical events: more daylight, the oceanographic spring transition, and the return of our beloved gray whales – just to name a few. On my own personal scale, I’ve been thinking about the cycles we experience as scientists a lot lately, since I’ve recently transitioned out of graduate school and into my current position as a postdoctoral scholar.

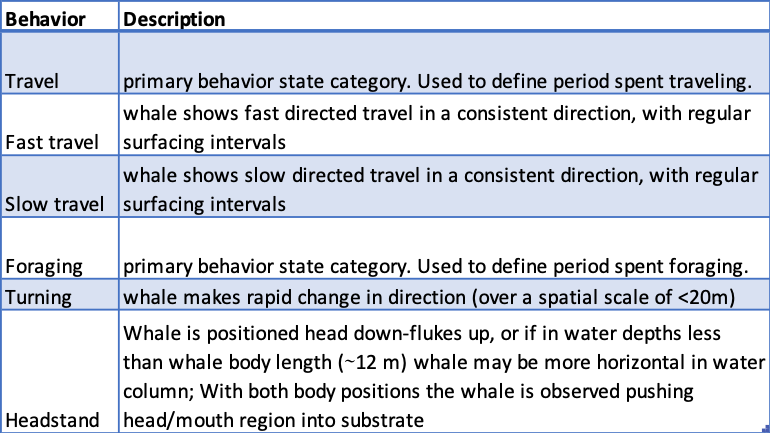

Starting this new postdoc has been a bit jarring, as it’s felt like starting over. Even though I’m still working at the Marine Mammal Institute and still studying gray whales, I’ve been learning new skills, knowledge and theory, which pushes me to re-start the cycle of the scientific method, the process we follow in research (Figure 1). Broadly, we start by observing a system and asking a question about a potential pattern or event we see. We then come up with a hypothesis (or two or ten) to address our question(s). The next steps are to collect the data we need to answer our question(s) and test our hypotheses, analyze that data (i.e. run some statistical models), and draw some conclusions from the analysis results. While it seems quite linear, the process of data collection and analysis always leads to more questions than answers, and we inevitably start the cycle all over again.

Throughout my scientific training I’ve gained experience in all these phases, but I’ve also learned just how many add-ons and do-overs there are in this process (Figure 2). Developing questions and hypotheses often requires a long and winding path through the literature, depending on how much you already know. These steps are often some of the first and biggest steps in graduate school. You need to learn as much as you can about the field and questions you are interested in, as this will inform what has already been done, where the knowledge gaps are, and the hypotheses you’re developing. For example, we often back up a hypothesis with references to studies that have answered our question in different systems. The learning curve is steep, and it’s important to not understate the work that goes into this phase. Early in my career, I remember hearing that “asking the good questions” is a critical skill for research. At the time that sounded like some vague, innate characteristic, and working to gain this ability felt ambiguous and overwhelming. I was absolutely wrong. Like most skills, knowing how to ask good questions is more about experience than intelligence. Here, experience is a combination of reading the literature and practice formulating questions based on the literature.

Beyond this lesson, I also had to learn that what qualifies a question as “good” also depends on the funding source. In many research institutions, including those in the U.S., scientists are responsible for finding the funding to run their research projects. Funding a project includes salary for the scientists (e.g., professors, grad students, post docs), the cost of collecting and analyzing the data (e.g., travel, equipment, boat time), and the cost of publishing and sharing our findings (e.g., publication costs). The programs we solicit funding from often have their own priorities, so a big part of the research cycle is finding a funding source that is interested in the kinds of questions you want to ask and then adjusting your own questions and hypotheses to align with the funding source’s priorities and budget. The actual application includes writing a proposal where we (1) summarize all the background research justifying the novelty and value of the questions we want to ask and backing up our hypotheses and (2) describe how we plan on answering those questions. Funding is competitive and we typically apply multiple times before being successful. Furthermore, we often apply to multiple funding sources to support the same project. Since each source has its own focus, this ends up being an exercise in coming up with multiple ways to frame and justify a project.

Once we have funding (which can be years after the start of the cycle), we can finally start collecting, analyzing, and interpreting the data. But each of these steps has its own sub-cycles and complexities. Data collection can take years and involve all kinds of troubleshooting equipment issues, logistics, and methods. Depending on your question, data processing and analysis may involve developing your own method. For example, our lab asks a lot of questions about the morphology and body condition of whales. But before we could answer those questions, we first had to work out the best way to accurately measure whales from drone imagery while accounting for measurement uncertainty (read more here). This separate cycle of method development involved so many sub-projects and new software tools that Dr. KC Bierlich now leads the Marine Mammal Institute’s Center of Drone Excellence (CODEX).

Data analysis and interpretation brings us back to the literature review part of the cycle. But now we are looking for examples of how similar data have been analyzed previously and for studies to which we can compare our results. Then, after testing out different models and triple checking our analysis, we’re finally ready to share our findings. We share our results through conference presentations, publications (after the peer review cycle), outreach talks, and press releases that lead to media pieces and interviews.

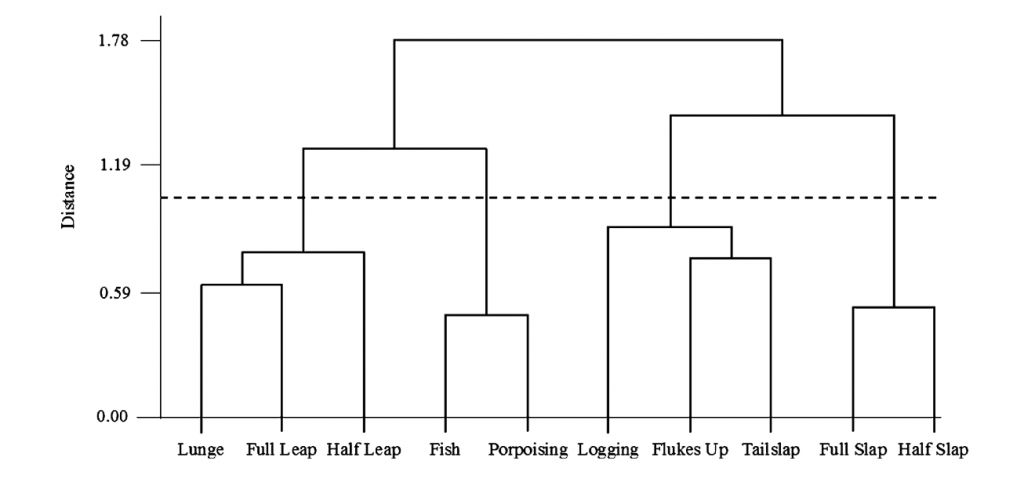

In addition to the excitement of sharing our findings with the world, we’re simultaneously hyper-aware of all the caveats and limitations of our work. We’re always left with a long list of follow-up questions, thus starting the cycle again. From a zoomed-out perspective these results can form a clean, linear story. But zooming in reveals the reality of years and years of multiple overlapping cycles that have had to pass roadblocks and restart countless times. For example, after nine years for research, the GRANITE project has produced an impressive suite of results addressing questions related to Pacific Coast Feeding Group gray whale morphology, health, hormones, space use, and behavior. It took years of data collection, proposal writing, training, and multiple researchers working through their own project cycles to get here (and we’re not done).

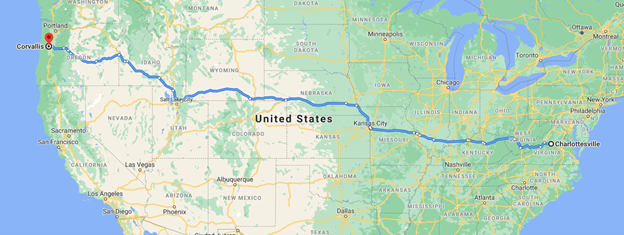

Transitioning out of graduate school has meant expanding my scope of attention to multiple cycles running in parallel, re-starting the literature review process for new projects, and spending a lot more time in the proposal writing sub-cycle. While it’s felt overwhelming at times, I’ve also enjoyed digging into new topics and skills. It’s an interesting balance of experiencing the discomfort that comes with being a beginner while simultaneously drawing comfort from the knowledge that I’ve experienced this cycle before and know how to learn something new.

A consequence of learning the scientific process is growing accustomed to this cyclical nature. As scientists we know that it’s a slow process, that every result is just the start of a new cycle, and that future work building on a result may agree or disagree with the previous finding. But the way scientific findings are shared with the public doesn’t necessarily reflect the process. Catchy headlines and brief summaries often present findings as definitive and satisfying conclusions to a story. Behind those headlines are years of set up, data collection, analysis, and a suite of caveats that we want to dig into in the future. The results of any given study reflect our best current knowledge at that point in the cycle. By design, that knowledge will grow and change as we move forward.

Did you enjoy this blog? Want to learn more about marine life, research, and conservation? Subscribe to our blog and get a weekly alert when we make a new post! Just add your name into the subscribe box below!