By Lisa Hildebrand, PhD student, OSU Department of Fisheries & Wildlife, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

Since early May, much of the GEMM Lab has been consumed by the GRANITE project, which stands for Gray whale Response to Ambient Noise Informed by Technology and Ecology. Two weeks ago, PhD student Clara Bird discussed our field work preparations, and since May 20th we have conducted five successful days of field work (and one unsuccessful day due to fog). If you are now expecting a blog about the data we have collected so far and whales we encountered, I am sorry to disappoint you. Rather, I want to take a big step back and provide the context of the GRANITE project as a whole, explain why this project and data collection is so important, and discuss what it is that we hope to achieve with our ever-growing, multidisciplinary dataset and team.

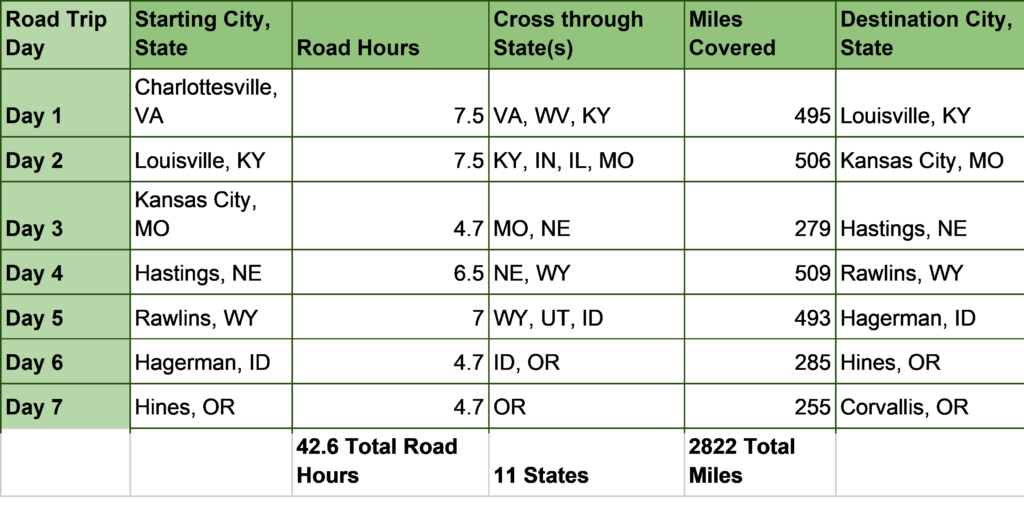

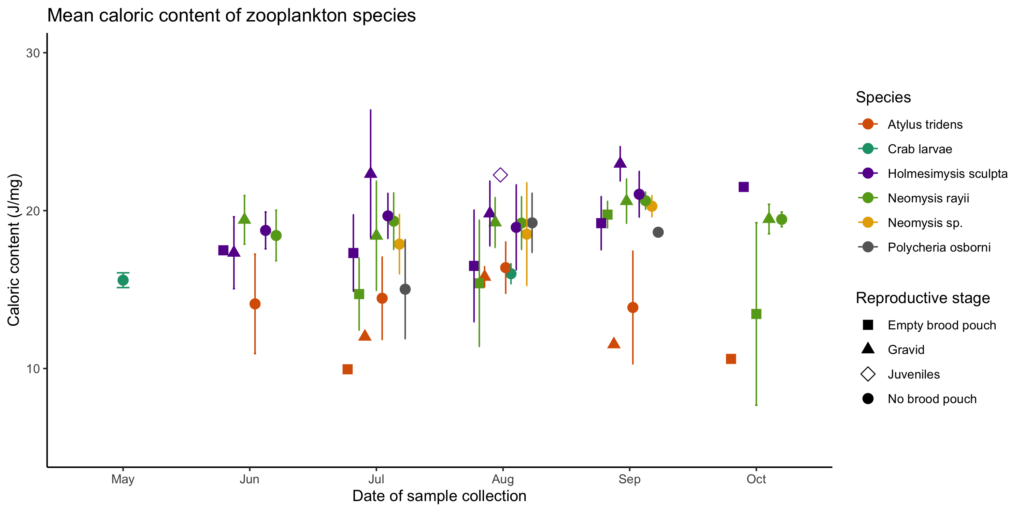

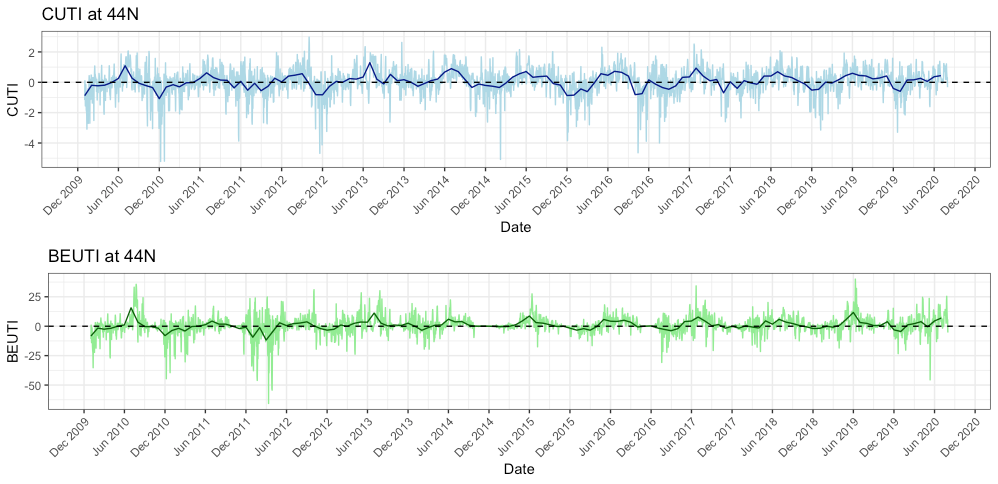

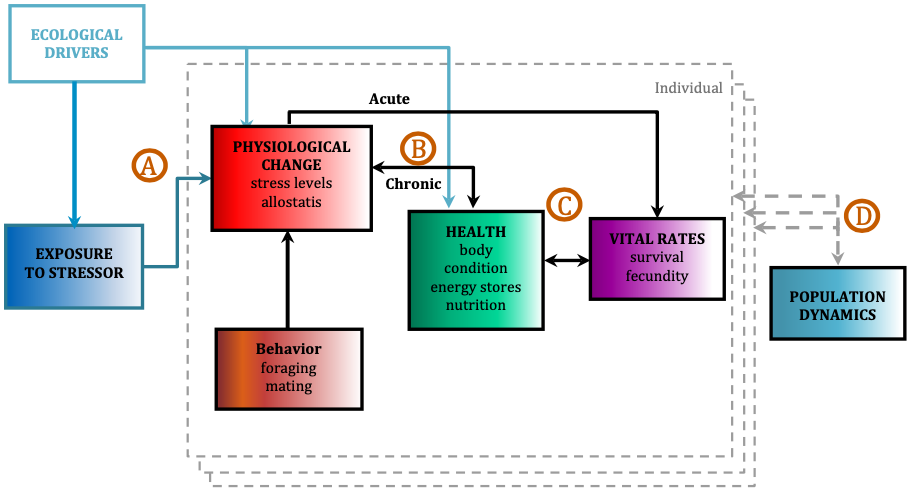

We use the Pacific Coast Feeding Group (PCFG) of gray whales that forage off the Oregon coast as our study system to better understand the ecological and physiological response of baleen whales to multiple stressors. Our field methodology includes replicate physiological and ecological sampling of this accessible baleen whale population with synoptic measurement of multiple types of stressors. We collect fecal samples for hormone analysis, conduct drone overflights of whales to collect body condition and behavioral data, record the ambient soundscape through deployment of two hydrophones, and conduct whale photo-identification to link all data streams to each individual whale of known sex, estimated age, and reproductive status. We resample these data from multiple individuals within and between summer foraging seasons, while exposed to different potential stressors occurring at different intensities and temporal periods and durations. The hydrophones are strategically placed with one in a heavily boat-trafficked (and therefore noisy) area close to the Port of Newport, while the second is located in a relatively calm (and therefore quieter) spot near the Otter Rock Marine Reserve (Fig. 1). These hydrophones provide us with information about both natural (e.g. killer whales, wind, waves) and anthropogenic (e.g. boat traffic, seismic survey, marine construction associated with PacWave wave energy facility development) noise that may affect gray whales. During sightings with whales, we also drop GoPro cameras and sample for prey to better understand the habitats where whales forage and what they might be consuming.

GEMM Lab PI Dr. Leigh Torres initiated this research project in 2015 and established partnerships with acoustician Dr. Joe Haxel and (then) PhD student Dr. Leila Lemos. Since then, the team working on this project has grown considerably to provide expertise in the various disciplines that the project integrates. Leigh is currently joined at the GRANITE helm by 4 co-PIs: Dr. Haxel, endocrinologist Dr. Kathleen Hunt, biological statistician Dr. Leslie New, and physiologist Dr. Loren Buck. Drs. Alejandro Fernandez Ajo, KC Bierlich and Enrico Pirotta are postdoctoral scholars who are working on the endocrinology, photogrammetry, and biostatistical modelling components, respectively. Finally, Clara and myself are partially funded through this project for our PhD research, with Clara focusing on the links between behavior, body condition, individualization, and habitat, while I am tackling questions about the recruitment and site fidelity of the PCFG (more about these topics below).

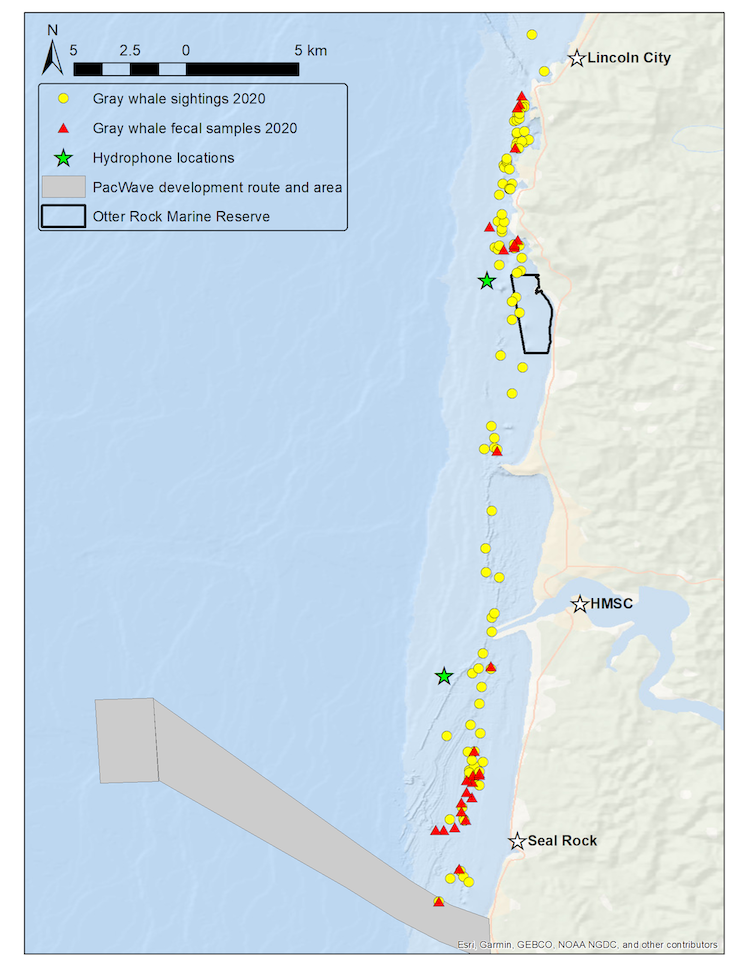

The ultimate goal of this project is to use the PCFG as a case study to quantify baleen whale physiological response to different stressors and model the subsequent impacts on the population by implementing our long-term, replicate dataset into a framework called Population consequences of disturbance (PCoD; Fig. 2). PCoD is built upon the underlying concept that changes in behavior and/or physiology caused by disturbance (i.e. noise) affect the fitness of individuals by impacting their health and vital rates, such as survival, reproductive success, and growth rate (Pirotta et al. 2018). These impacts at the individual level may (or may not) affect the population as a whole, depending on what proportion of individuals in the population are affected by the disturbance and the intensity of the disturbance effect on each individual. The PCoD framework requires quantification of four stages: a) the physiological and/or behavioral changes that occur as a result of exposure to a stressor (i.e. noise), b) the acute effects of these physiological and/or behavioral responses on individual vital rates, and their chronic effects via individual health, c) the way in which changes in health may affect the vital rates of individuals, and d) how changes in individual vital rates may affect population dynamics (Fig. 2; Pirotta et al. 2018). While four stages may not sound like a lot, the amount and longevity of data needed to quantify each stage is immense.

The ability to detect a change in behavior or physiology often requires an understanding of what is “normal” for an individual, which we commonly refer to as a baseline. The best way to establish a baseline is to collect comprehensive data over a long time period. With our data collection efforts since 2015 of fecal samples, drone flights and photo identification, we have established useful baselines of behavioral and physiological data for PCFG gray whales. These baselines are particularly impressive since it is typically difficult to collect repeated measurements of hormones and body condition from the same individual baleen whale across multiple years. These repeated measurements are important because, like all mammals, hormones and body condition vary across life history phases (i.e., with pregnancy, injury, or age class) and across time (i.e., good or bad foraging conditions). To achieve these repeated measurements, GRANITE exploits the high degree of intra- and inter-annual site fidelity of the PCFG, their accessibility for study due to their affinity for nearshore habitat use, and the long-term sighting history of many whales that provides sex and approximate age information. Our work to-date has already established a few important baselines. We now know that the body condition of PCFG gray whales increases throughout a foraging season and can fluctuate considerably between years (Soledade Lemos et al. 2020). Furthermore, there are significant differences in body condition by reproductive state, with calves and pregnant females displaying higher body conditions (Soledade Lemos et al. 2020). Our dataset has also allowed us to validate and quantify fecal steroid and thyroid hormone metabolite concentrations, providing us with putative thresholds to identify a stressed vs. not stressed whale based on its hormone levels (Lemos et al. 2020).

We continue to collect data to improve our understanding of baseline PCFG physiology and behavior, and to detect changes in their behavior and physiology due to disturbance events. All these data will be incorporated into a PCoD framework to scale from individual to population level understanding of impacts. However, more data is not the only thing we need to quantify each of the PCoD stages. The implementation of the PCoD framework also depends on understanding several aspects of the PCFG’s population dynamics. Specifically, we need to know whether recruitment to the PCFG population occurs internally (calves born from “PCFG mothers” return to the PCFG) or externally (immigrants from the larger Eastern North Pacific gray whale population joining the PCFG as adults). The degree of internal or external recruitment to the PCFG population should be included in the PCoD model as a parameter, as it will influence how much individual level disturbance effects impact the overall health and viability of the population. Furthermore, knowing residency times and home ranges of whales within the PCFG is essential to understand exposure durations to disturbance events.

To assess both recruitment and residency patterns of the PCFG, I am undertaking a large photo-identification effort, which includes compiling sightings and photo data across many years, regions, and collaborators. Through this effort we aim to identify calves and their return rate to the population, the rate of new adult recruits to the population, and the spatial residency of individuals in our study system. Although photo-id is a basic, commonplace method in marine mammal science, its role is critical to tracking individuals over time to understand population dynamics (in a non-invasive manner, no less). A large portion of my PhD research will focus on the tedious yet rewarding task of photo-id data management and matching in order to address these pressing knowledge gaps on PCFG population dynamics needed to implement the PCoD model that is an ultimate goal of GRANITE. I am just beginning this journey and have already pinpointed many analytical and logistical hurdles that I need to overcome. I do not anticipate an easy path to addressing these questions, but I am extremely eager to dig into the data, reveal the patterns, and integrate the findings into our rock-solid GRANITE project.

Funding for the GRANITE project comes from the Office of Naval Research, the Department of Energy, Oregon Sea Grant, the NOAA/NMFS Ocean Acoustics Program, and the OSU Marine Mammal Institute.

References

Lemos, L.S., Olsen, A., Smith, A., Chandler, T.E., Larson, S., Hunt, K., and L.G. Torres. 2020. Assessment of fecal steroid and thyroid hormone metabolites in eastern North Pacific gray whales. Conservation Physiology 8:coaa110.

Pirotta, E., Booth, C.G., Costa, D.P., Fleishman, E., Kraus, S.D., Lusseau, D., Moretti, D., New, L.F., Schick, R.S., Schwarz, L.K., Simmons, S.E., Thomas, L., Tyack, P.L., Weise, M.J., Wells, R.S., and J. Harwood. 2018. Understanding the population consequences of disturbance. Ecology and Evolution 8(19):9934-9946.

Soledade Lemos, L., Burnett, J.D., Chandler, T.E., Sumich, J.L., and L.G. Torres. 2020. Intra- and inter-annual variation in gray whale body condition on a foraging ground. Ecosphere 11(4):e03094.