Mariam Alsaid, University of California Berkeley, GEMM Lab REU Intern

My name is Mariam Alsaid and I am currently a 5th year undergraduate transfer student at the University of California, Berkeley. Growing up on the small island of Bahrain, I was always minutes away from the water and was enraptured by the creatures that lie beneath the surface. Despite my long-standing interest in marine science, I never had the opportunity to explore it until just a few months ago. My professional background up until this point was predominantly in soil microbiology through my work with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and I was anxious about how I would switch directions and finally be able to pursue my main passion. For this reason, I was thrilled by my acceptance into the OSU Hatfield Marine Science Center’s REU program this year, which led to my exciting collaboration with the GEMM Lab. It was kind of a silly transition to go from studying bacteria, one of the smallest organisms on earth, to whales, who are the largest.

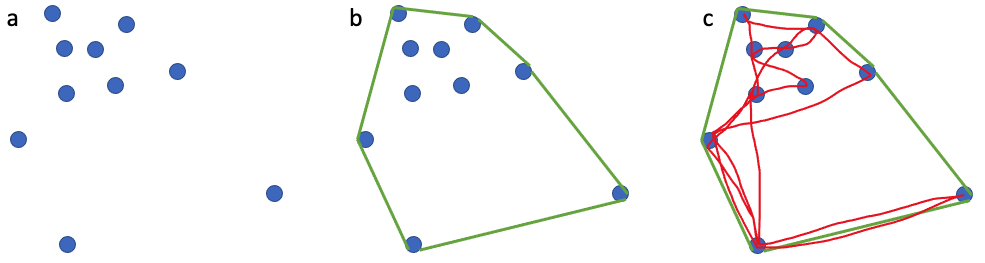

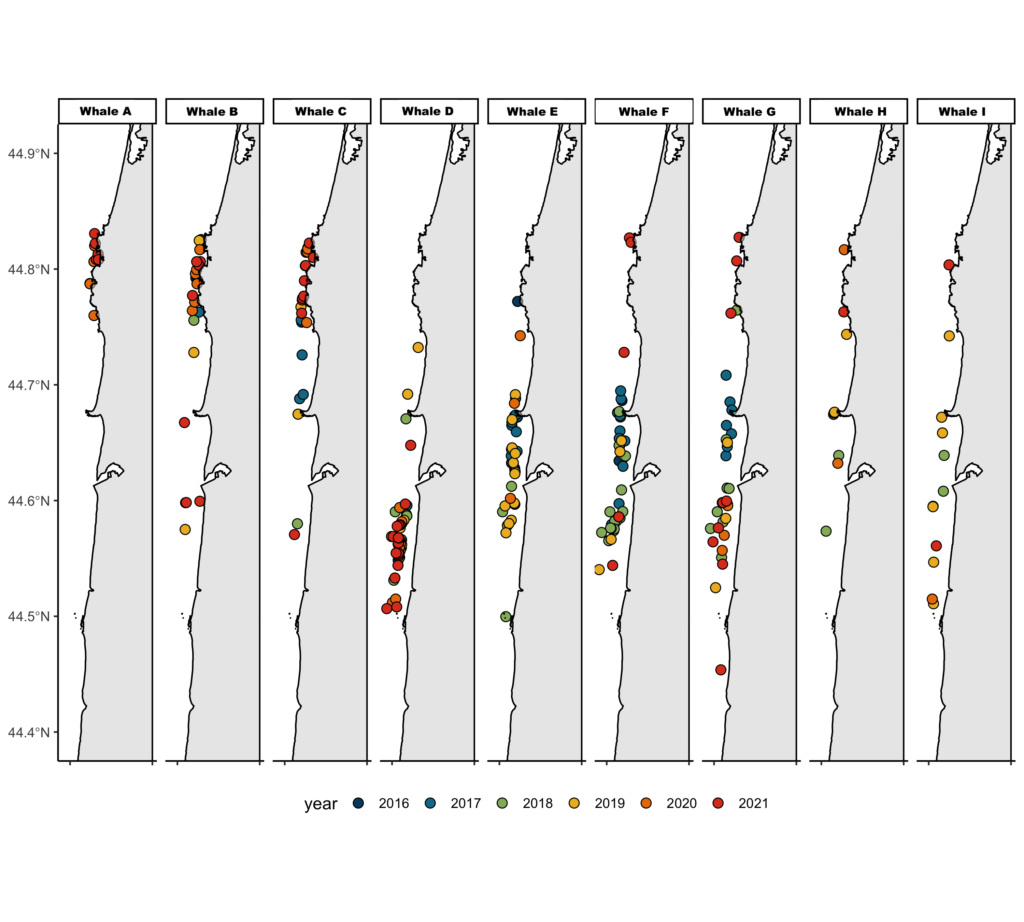

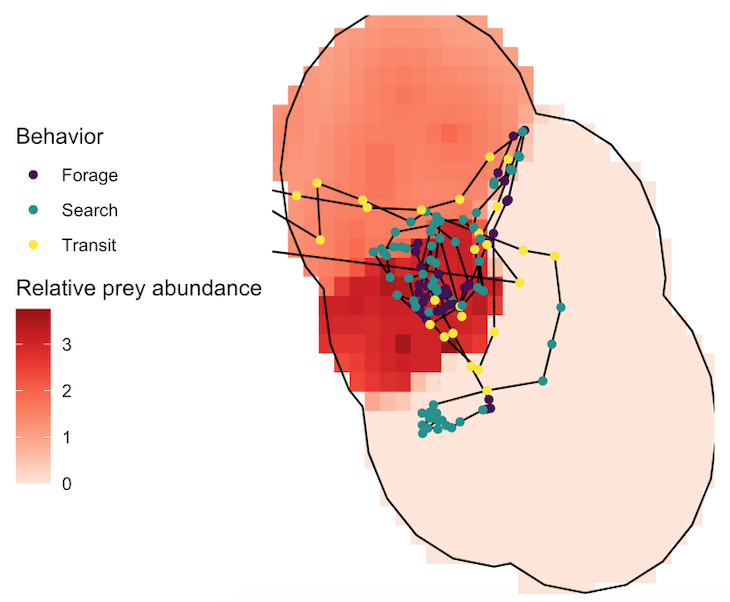

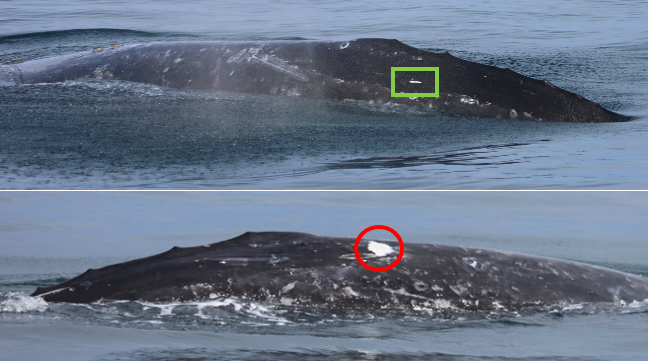

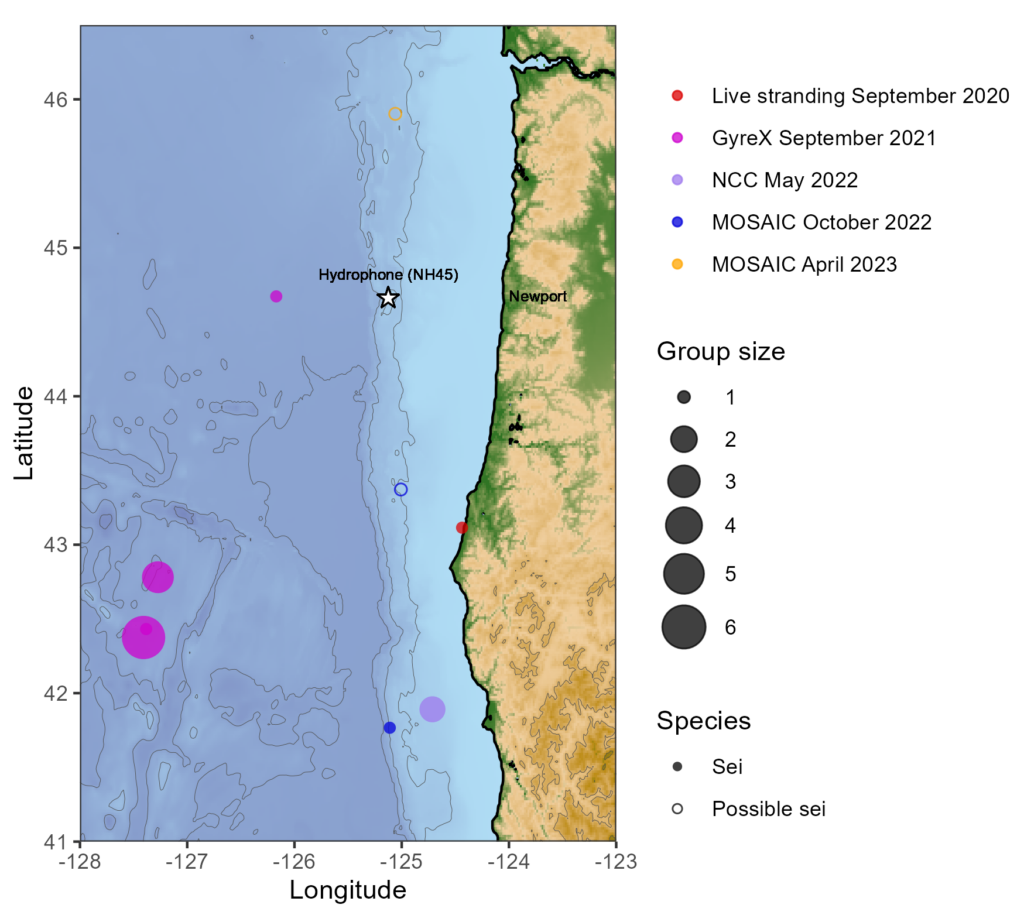

My project this summer focused on sei whale acoustic occurrence off the coast of Oregon. “What’s a sei whale?” is a question I heard a lot throughout the summer and is one that I had to Google myself several times before starting my internship. Believe it or not, sei whales are the third largest rorqual in the world but don’t get much publicity because of their small population sizes and secretive behavior. The commercial whaling industry of the 19th and 20th centuries did a number on sei whale populations globally, rendering them endangered. In consequence, little research has been conducted on their global range, habitat use, and behavior since the ban of commercial whaling in 1986 (Nieukirk et al. 2020). Additionally, sei whales are relatively challenging to study because of their physical similarities to the fin whale, and acoustic similarities to other rorqual vocalizations, most notably blue whale D-calls and fin whale 40 Hz calls. As of today, published literature indicates that sei whale acoustic presence in the Pacific Ocean is restricted to Antarctica, Chile, Hawaii, and possibly British Columbia, Canada (Mcdonald et al. 2005; Espanol-Jiminez et al. 2019; Rankin and Barlow, 2012; Burnham et al. 2019). The idea behind this research project was sparked by sparse visual sightings of sei whales by research cruises conducted by the Marine Mammal Institute (MMI) in recent years (Figure 1). This raised questions about if sei whales are really present in Oregon waters (and not just misidentified fin whales) and if so, how often?

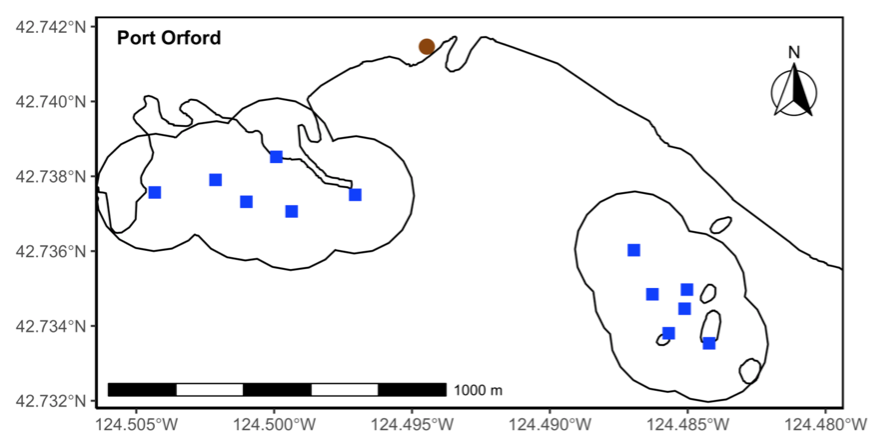

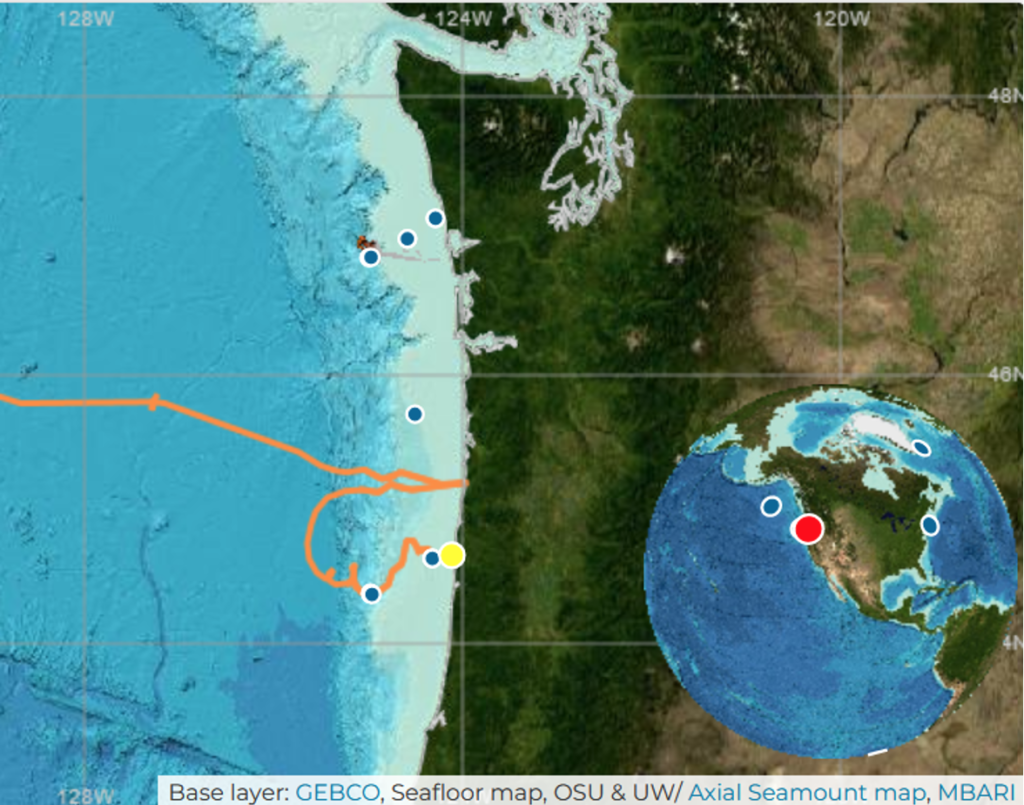

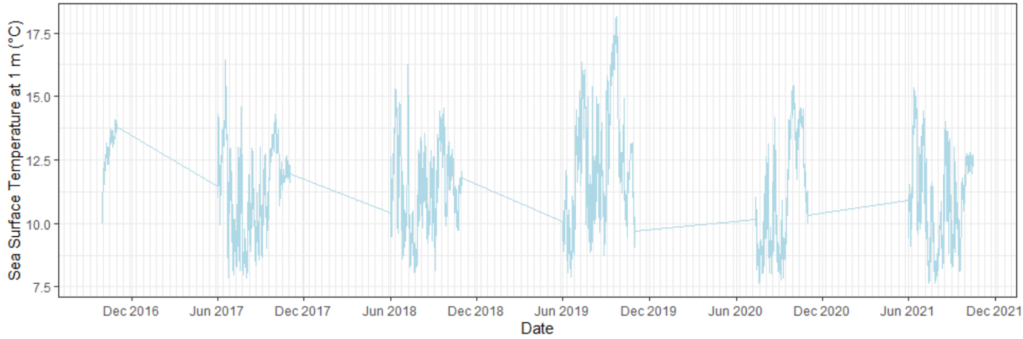

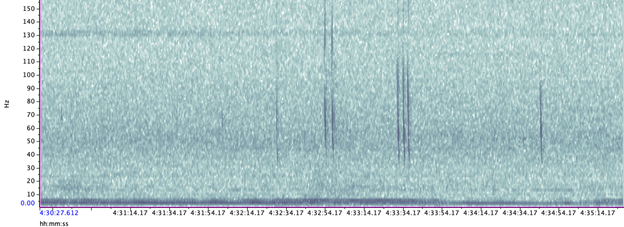

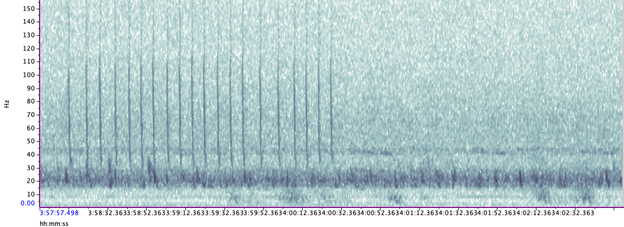

A hydrophone, which is a fancy piece of equipment that records continuous underwater sound, was deployed 45 miles offshore of Newport, OR between October of 2021 and December of 2022. My role this summer was to use this acoustic data to determine whether sei whales are hanging out in Oregon or not. Acoustic data was analyzed using the software Raven Pro, which allowed me to visualize sound in the form of spectrograms (Fig. 2). From there, my task was to select signals that could potentially be sei whale calls. It was a hurdle familiarizing myself with sei whale vocalizations while also keeping in mind that other species (e.g., blue and fin whales) may produce similar sounding (and looking in the spectrograms) calls. For this reason, I decided to establish confidence levels based on published sei whale acoustic research that would help me classify calls with less bias. Vocalizations produced by sei whales are characterized by low frequency, broadband, downsweeps. Sei whales can be acoustically distinguished from other whales because of their tendency to produce uniform groups of calls (typically in doublets and triplets) in a short timeframe. This key finding allowed me to navigate the acoustic data with more ease.

The majority of the summer was spent slowly scanning through the months of data at 5-minute increments. As you can imagine, excitement varied by day. Some days I would find insanely clear signals of blue, fin, and humpback whales and other days I would find nothing. The major discovery and the light at the end of the tunnel was the SEI WHALES!!! I detected numerous high quality sei whale calls throughout the study period with peaks in October and November (but a significantly higher peak in occurrence in 2022 versus 2021). I also encountered a unique vocalization type in fall of 2022, consisting of a very long series of repeated calls that we called “multiplet”, rather than doublets or triplets that is more typical of sei whales (Fig. 3). Lastly, I found no significant diel pattern in sei whale vocalization, indicating that these animals call at any hour of the day. More research needs to go into this project to better estimate sei whale occurrence and understand their behavior in Oregon but this preliminary work provides a great baseline into what sei whales sound like in this part of the world. In the future, the GEMM lab intends on implementing more hydrophone data and work on developing an automated detection system that would identify sei whale calls automatically.

My experience this summer was so formative for me. As someone who has been an aspiring marine biologist for so long, I am so grateful for my experience working with the GEMM Lab alongside incredible scientists who are equally passionate about studying the mysteries of the ocean. This experience has also piqued my interest in bioacoustics and I plan on searching for other opportunities to explore the field in the future. Aside from growing professionally, I learned that I am more capable of tackling and overcoming obstacles than I had thought. I was afraid of entering a field that I knew so little about and was worried about failing and not fitting in. My anxieties were overshadowed by the welcoming atmosphere at Hatfield and I could not have asked for better people to work with. As I was searching for sei whale calls this summer, I suppose that I was also unintentionally searching for my voice as a young scientist in a great, blue field.

Did you enjoy this blog? Want to learn more about marine life, research, and conservation? Subscribe to our blog and get a weekly alert when we make a new post! Just add your name into the subscribe box below!

References:

Nieukirk, S. L., Mellinger, D. K., Dziak, R. P., Matsumoto, H., & Klinck, H. (2020). Multi-year occurrence of sei whale calls in North Atlantic polar waters. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 147(3), 1842–1850. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0000931

McDonald, M. A., Calambokidis, J., Teranishi, A. M., & Hildebrand, J. A. (2001). The acoustic calls of blue whales off California with gender data. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 109(4), 1728–1735. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1353593

Español-Jiménez, S., Bahamonde, P. A., Chiang, G., & Häussermann, V. (2019). Discovering sounds in Patagonia: Characterizing sei whale (<i>Balaenoptera borealis</i>) downsweeps in the south-eastern Pacific Ocean. Ocean Science, 15(1), 75–82. https://doi.org/10.5194/os-15-75-2019

Rankin, S., & Barlow, J. (2007). VOCALIZATIONS OF THE SEI WHALE BALAENOPTERA BOREALIS OFF THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS. Bioacoustics, 16(2), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/09524622.2007.9753572

Burnham, R. E., Duffus, D. A., & Mouy, X. (2019). The presence of large whale species in Clayoquot Sound and its offshore waters. Continental Shelf Research, 177, 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2019.03.004