By: Marissa Garcia, PhD Student, Cornell University, Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, K. Lisa Yang Center for Conservation Bioacoustics

Predator-Prey Inference: A Tale as Old as Time

It’s a tale as old as time: where there’s prey, there’ll be predators.

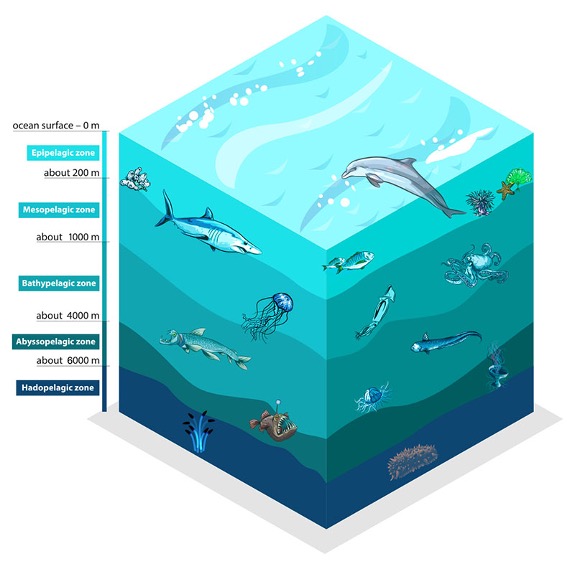

As apex predators, cetaceans act as top-down regulators of ecosystem function. While baleen whales act as “ecosystem engineers,” facilitating nutrient cycling in the ocean (Roman et al., 2014), toothed whales, or “odontocetes,” can impart keystone-level effects — that is, they disproportionately control the marine community’s food-web structure (Valls, Coll, & Christensen, 2015). The menus of prey vary widely by species — ranging from mircronekton to fish to squid – and by extension, vary widely across trophic levels.

So, it naturally follows the old adage: where there’s an abundance of prey, there’ll be an abundance of cetaceans. Yet, creating models that accurately depict this predator-prey relationship is, perhaps unsurprisingly, not as straightforward.

Detecting the ‘Predator’ Half of the Equation

Scientists have successfully documented cetacean presence drawing upon a myriad of methods, each bearing its unique advantages and limitations.

Visual surveys — spanning viewpoints from land, boats, and air — can attain precise spatial data and species ID. However, this data can be constrained by “availability bias” — that is, scientists can only observe cetaceans visible at the surface, not those obscured by the ocean’s depths. Species that spend less time near the surface are more likely to elude the observer’s line of sight, thereby being missed in the data. Consequently, visual surveys have historically undersampled deep-diving species. For instance, since its discovery by western science in 1945, the Hubb’s beaked whale (Mesoplodon carlshubbi) has only been observed alive twice by OSU MMI’s very own Bob Pitman, once in 1994 and another time in 2021.

Scientists have also been increasingly conducting acoustic surveys to document cetacean presence. Acoustic recorders can “hear” each cetacean species at different ranges. Baleen whales, which bellow low-frequency calls, can be heard as far as across ocean basins (Munk et al., 1994). Toothed whales whistle, echolocate, and buzz at frequencies so high they’re considered ultrasonic. But it comes at a trade-off: high-frequency sounds have shorter wavelengths, meaning they are heard across smaller ranges. This high variability, which scientists refer to as “detection range,” translates to not always knowing where the vocalizing cetacean that was recorded is: as such, acoustic data can lack the high-resolution spatial precision often achieved by visual surveys. Nevertheless, acoustic data triumphs in temporal extent, sometimes managing to record continuously at six months at a time. Additionally, animals can elude visual detection in poor weather conditions or if they have a cryptic surface expression, but detected in acoustic surveys (e.g., North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) (Ganley, Brault, & Mayo, 2019; Clark et. al, 2010). Thus, acoustic surveys may be especially optimal for recording elusive deep-dwellers that occupy the often rough Oregon waters, such as beaked whales, the focus of my research in collaboration with the GEMM Lab.

Detecting the ‘Prey’ Half of the Equation

Prey can be measured by numerous methods. Most directly, prey can be measured “in-situ” — that is, prey is collected directly from the site where the cetaceans are detected or observed. A 2020 study combined fish trawls with a towed hydrophone array to identify which fish species odontocetes along the continental shelf of West Ireland (e.g., pilot whales, sperm whales, and Sowerby’s beaked whales) were feasting; the results found that odontocetes primarily fed upon mesopelagic fish and cephalopods (Breen et al., 2020). While trawls can glean species ID of prey, associating this prey data with depth and biomass can prove challenging.

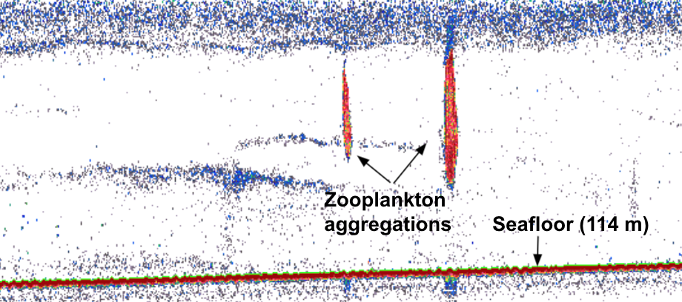

Alternatively, prey can be detected via active acoustics. Echosounders release an acoustic signal that descends through the water column and then echoes back once it hits a sound-scattering organism. Beaked whales forage within deep scattering layers typically composed of myctophid fish and squid, both of which can echo back echosounder pings (Hazen et al., 2011). Thus, echosounder data can map prey density through the water column. When mapping prey density of beaked whales, Hazen et al. 2011 found a strong positive correlation among prey density, ocean vertical structure, and clicks primarily produced while foraging – suggesting beaked whales forage at depth when encountering large, multi-species aggregations of prey.

Most relevant to the HALO Project, prey is measured using proximate indices, which are more easily quantifiable metrics of ocean conditions, such as collected from ships via CTD casts or via satellite imagery, that are indirectly related to prey abundance. CTD data can provide information related to the water column structure, including depth and strength of the thermocline, depth of the mixed layer, depth of the euphotic zone, and total chlorophyll concentration in the euphotic zone (Redfern et al. 2006). Satellite imagery can characterize the dynamic patterns of the surface later, including sea surface temperature (SST), salinity, surface chlorophyll a, sea surface height (SSH), and sea surface currents (Virgili et al., 2022; Redfern et al., 2006). Ocean model data products can, such as the Regional Ocean Modeling System (ROMS) which models how an oceanic region of interest responds to physical processes, can provide water column variables related to eddy kinetic energy (EKE) and average temperature gradients (Virgili et al., 2022). In the case of my research with the HALO Project, we will be using oceanographic data collected through the Ocean Observatories Initiative to inform odontocete species distribution models.

Connecting the Dots: Linking Deep-Dwelling Top Predators and Prey

While scientists have made significant advances with collecting both cetacean and prey data, connecting the dots between the ecology of deep-dwelling odontocetes and the oceanographic parameters indicative of their prey still remains a challenge.

In the absence of in situ sampling, species distribution models of marine top predators often derive proxies for “prey data” from static bathymetric and dynamic surface water variables (Virgili et al., 2022). However, surface variables may be irrelevant to toothed whale prey inhabiting great depths (Virgili et al., 2022). Within the HALO Project, the deepest Rockhopper acoustic recording unit is recording odontocetes at nearly 3,000 m below the surface, putting into question the relevance of oceanographic parameters collected at the surface.

In my research, I am setting out to estimate which oceanographic variables are optimal for explaining deep-dwelling odontocete presence. A 2022 study using visual survey data found that surface, subsurface, and static variables best explained beaked whale presence, whereas only surface and deep-water variables – not static – best explained sperm whale presence (Virgili et al., 2022). These results are associated with each species’ distinct foraging ecologies; beaked whales may truly only rely on organisms that live near the seabed, whereas sperm whales also feast upon meso-to-bathypelagic organisms, so they may be more sensitive to changes in water column conditions (Virgili et al., 2022). This study expanded the narrative: deep-water variables can also be key to predicting deep-dwelling odontocete presence. The oceanographic variables must be tailored to the ecology of each species of interest.

In the months ahead, I seek to build on this study by investigating which parameters best predict odontocete presence using an acoustic approach instead — I am looking forward to the results to come!

References

Breen, P., Pirotta, E., Allcock, L., Bennison, A., Boisseau, O., Bouch, P., Hearty, A., Jessopp, M., Kavanagh, A., Taite, M., & Rogan, E. (2020). Insights into the habitat of deep diving odontocetes around a canyon system in the northeast Atlantic ocean from a short multidisciplinary survey. Deep-Sea Research. Part I, Oceanographic Research Papers, 159, 103236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2020.103236

Clark, C.W., Brown, M.W., & Corkeron, P. (2010). Visual and acoustic surveys

for North Atlantic right whales, Eubalaena glacialis, in Cape Cod Bay, Massachusetts, 2001–2005: Management implications. Marine Mammal Science, 26(4), 837-854.

Ganley, L.C., Brault, S., & Mayo, C.A. (2019). What we see is not what there is: Estimating North Atlantic right whale Eubalaena glacialis local abundance. Endangered Species Research, 38, 101-113.

Hazen, E. L., Nowacek, D. P., St Laurent, L., Halpin, P. N., & Moretti, D. J. (2011). The relationship among oceanography, prey fields, and beaked whale foraging habitat in the Tongue of the Ocean. PloS One, 6(4), e19269–e19269.

Munk, W. H., Spindel, R. C., Baggeroer, A., & Birdsall, T. G. (1994). The Heard Island Feasibility Test. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 96(4), 2330–2342. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.410105

Redfern, J. V., Ferguson, M. C., Becker, E. A., Hyrenbach, K. D., Good, C., Barlow, J., Kaschner, K., Baumgartner, M. F., Forney, K. A., Ballance, L. T., Fauchald, P., Halpin, P., Hamazaki, T., Pershing, A. J., Qian, S. S., Read, A., Reilly, S. B., Torres, L., & Werner, F. (2006). Techniques for cetacean–habitat modeling. Marine Ecology. Progress Series (Halstenbek), 310, 271–295.

Roman, J., Estes, J. A., Morissette, L., Smith, C., Costa, D., McCarthy, J., Nation, J., Nicol, S., Pershing, A., & Smetacek, V. (2014). Whales as marine ecosystem engineers. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 12(7), 377–385.

Valls, A., Coll, M., & Christensen, V. (2015). Keystone species: toward an operational concept for marine biodiversity conservation. Ecological Monographs, 85(1), 29–47.

Virgili, A., Teillard, V., Dorémus, G., Dunn, T. E., Laran, S., Lewis, M., Louzao, M., Martínez-Cedeira, J., Pettex, E., Ruiz, L., Saavedra, C., Santos, M. B., Van Canneyt, O., Vázquez Bonales, J. A., & Ridoux, V. (2022). Deep ocean drivers better explain habitat preferences of sperm whales Physeter macrocephalus than beaked whales in the Bay of Biscay. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 9620–9620.