By Lindsay Wickman, Postdoctoral Scholar, Oregon State University Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

Previously on our blog, we mentioned the concerning rise of humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) entanglement in fishing gear on the US West Coast (see here and here). Gaining an improved understanding of the rate of entanglement and risk factors of humpback whales in Oregon are primary aims of the GEMM Lab’s SLATE and OPAL projects. In this post, I will discuss some reasons why whales get entangled. With whales generally regarded as intelligent, it is understandable to wonder why whales are unable to avoid these underwater obstacles.

Fishing lines are hard to detect underwater

Water clarity, depth, and time of day can all influence how visible a fishing line is underwater. Since baleen whales lack the ability to discriminate color (Levenson et al., 2000; Peichl et al. 2001), the brightly colored yellow and red ropes that make it easier for fishermen to find their gear make it harder for whales to see it underwater. White or black ropes may stand out better for whales (Kot et al., 2012), but there’s not enough evidence yet to suggest they reduce entanglement rates.

Whales have excellent hearing, but this may still not be enough to ensure detection of underwater ropes. Even if whales can hear water currents flowing over the rope, this noise can easily be masked by other sounds like weather, surf, and passing boats. Fishing gear also has a weak acoustic signature (Leatherwood et al., 1977), or it may be at a frequency not heard by whales. So even though whales produce and listen for sounds to help locate prey (Stimpert et al., 2007) and communicate, any sound produced by fishing lines may not be sufficient to alert whales to its presence.

There are very few studies that examine the behavior of whales around fishing gear, but a study of minke whales (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) by Kot et al. (2017) provides an exception. Researchers observed whales slowing down as they approached their test gear, and speeding up once they were past it (Kot et al., 2017). While the scope of the study was too small to generalize about whales’ ability to detect fishing gear, it does suggest whales can detect fishing gear, at least some of the time. There is also likely some individual variation in this skillset. Less experienced, juvenile humpback whales, for example, may be at a higher risk of entanglement than adults (Robbins, 2012).

Distracted driving?

Just like distracted drivers are more likely to crash when texting or eating, whales may be more likely to get entangled when they are preoccupied with behaviors like feeding or socializing.

Evidence suggests feeding is especially risky for entanglement. An analysis of entanglements in the North Atlantic found that almost half (43%) of the humpback whales were entangled at the mouth, and the mouth was also the most common attachment point for North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis, 77%; Johnson et al., 2005). In a study of minke whales in the East Sea of Korea, 80% of entangled whales had recently fed (Song et al, 2010). In many cases, entanglement at the mouth can severely restrict feeding ability, resulting in emaciation and/or death (Moore and van der Hoop, 2012).

More whales, more heat waves, and more entanglements

On the US West Coast, the number of humpback whales has been increasing since the end of whaling (e.g., Barlow et al, 2011). With more whales in our waters, it makes sense that the number of entanglements will increase. Still, a larger population size is probably not the only reason for increasing entanglements.

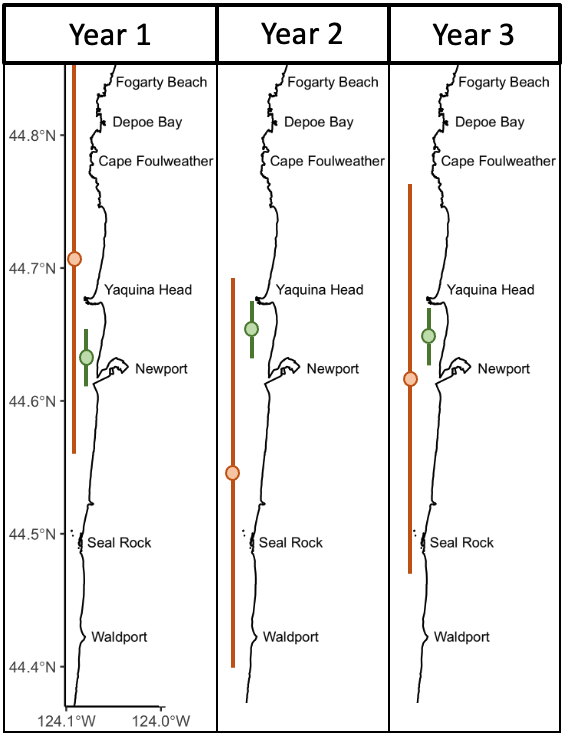

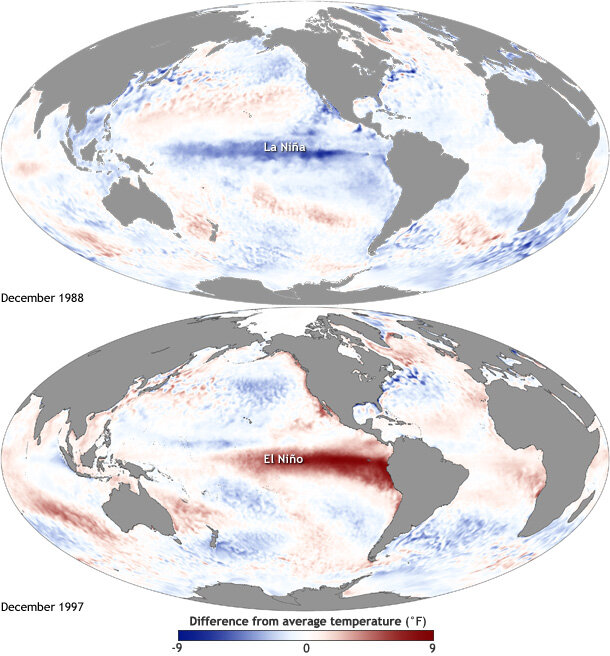

Climate change, for example, may place whales in the areas with dense fishing gear much more often. A recent example of this was during 2014–2016, when a heatwave on the US West Coast led to a cascade of events that increased the likelihood of whale entanglements in California waters (Santora et al., 2020).

The increased temperatures led to a bloom of toxic diatoms, which delayed the commercial fishing season for Dungeness crabs in California. Unfortunately, the delay caused fishing to resume right as high numbers of whales were arriving from their annual migration from their breeding grounds. The wider ecosystem effects of the heat wave also meant humpback whales were feeding closer to shore — right where most crab pots are set. The combination of both the fisheries’ timing and the altered distribution of whales contributed to an unprecedented number of entanglements (Santora et al., 2020).

Whale entanglement is a concerning issue for fishermen, conservationists, and wildlife managers. By disentangling some of the whys of entanglement for humpback whales in Oregon, we hope our research can contribute to improved management plans that benefit both whales and the continuity of the Dungeness crab fishery. To learn more about these projects, visit the SLATE and OPAL pages, and subscribe to the blog for more updates.

Did you enjoy this blog? Want to learn more about marine life, research, and conservation? Subscribe to our blog and get a weekly message when we post a new blog. Just add your name and email into the subscribe box below.

References

Barlow, J., Calambokidis, J., Falcone, E.A., Baker, C.S., Burdin, A.M., Clapham, P.J., Ford, J.K., Gabriele, C.M., LeDuc, R., Mattila, D.K. and Quinn, T.J. (2011). Humpback whale abundance in the North Pacific estimated by photographic capture‐recapture with bias correction from simulation studies. Marine Mammal Science, 27(4), 793-818.

Johnson, A., Salvador, G., Kenney, J., Robbins, J., Kraus, S., Landry, S., and Clapham, P. (2005). Fishing gear involved in entanglements of right and humpback whales. Marine Mammal Science, 21, 635–645.

Kot, B.W., Sears, R., Anis, A., Nowacek, D.P., Gedamke, J. and Marshall, C.D. (2012). Behavioral responses of minke whales (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) to experimental fishing gear in a coastal environment. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 413, pp.13-20.

Leatherwood, J.S., Johnson, R.A., Ljungblad, D.K., and Evans, W.E. (1977). Broadband Measurements of Underwater Acoustic Target Strengths of Panels of Tuna Nets. Naval Oceans Systems Center, San Diego, CA Tech, Rep. 126.

Levenson, D.H., Dizon, A., and Ponganis, P.J. (2000). Identification of loss-of-function mutations within the short wave-length sensitive cone opsin genes of baleen and odontocete cetaceans. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 41, S610.

Moore, M. J., and van der Hoop, J. M. (2012). The painful side of trap and fixed net fisheries: chronic entanglement of large whales. Journal of Marine Sciences, 2012.

Peichl, L., Behrmann, and G., Kröger, R.H.H. (2001). For whales and seals the ocean is not blue: a visual pigment loss in marine mammals. European Journal of Neuroscience, 13, 1520–1528.

Robbins J. (2012). Scar-based inference Into Gulf of Maine humpback whale entanglement: 2010. Report EA133F0 9CN0253 to the Northeast Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service. Center for Coastal Studies, Provincetown, MA.

Santora, J. A., Mantua, N. J., Schroeder, I. D., Field, J. C., Hazen, E. L., Bograd, S. J., Sydeman, W. J., Wells, B. K., Calambokidis, J., Saez, L., Lawson, D., and Forney, K. A. (2020). Habitat compression and ecosystem shifts as potential links between marine heatwave and record whale entanglements. Nature Communications, 11(1).

Song, K.-J., Kim, Z.G., Zhang, C.I., Kim, Y.H. (2010). Fishing gears involved in entanglements of minke whales (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) in the east sea of Korea. Marine Mammal Science, 26, 282–295.

Stimpert, A.K., Wiley, D.N., Au, W.W.L., Johnson, M.P., Arsenault, R. (2007). “Megapclicks”: acoustic click trains and buzzes produced during night-time foraging of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae). Biology Letters, 3, 467–470.