Dr. KC Bierlich, Postdoctoral Scholar, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, & Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna (GEMM) Lab

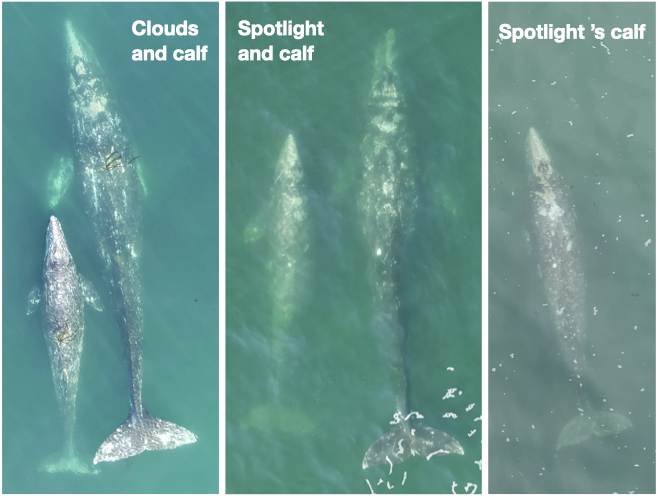

A recent blog post by GEMM Lab’s PhD Candidate Clara Bird gave a recap of our 8th consecutive GRANITEfield season this year. In her blog, Clara highlighted that we saw 71 individual gray whales this season, 61 of which we have seen in previous years and identified as belonging to the Pacific Coast Feeding Group (PCFG). With an estimated population size of around 212 individuals, this means that we saw almost 1/3 of the PCFG population this season alone. Since the GEMM Lab first started collecting data on PCFG gray whales in 2016, we have collected drone imagery on over 120 individuals, which is over half the PCFG population. This dataset provides incredible opportunity to get to know these individuals and observe them from year to year as they grow and mature through different life history stages, such as producing a calf. A question our research team has been interested in is what makes a PCFG whale different from an Eastern North Pacific (ENP) gray whale, which has a population size around 16,000 individuals and feed predominantly in the Arctic during the summer months? For this blog, I will highlight findings from our recent publication in Biology Letters (Bierlich et al., 2023) comparing the morphology (body length, skull, and fluke size) between PCFG and ENP populations.

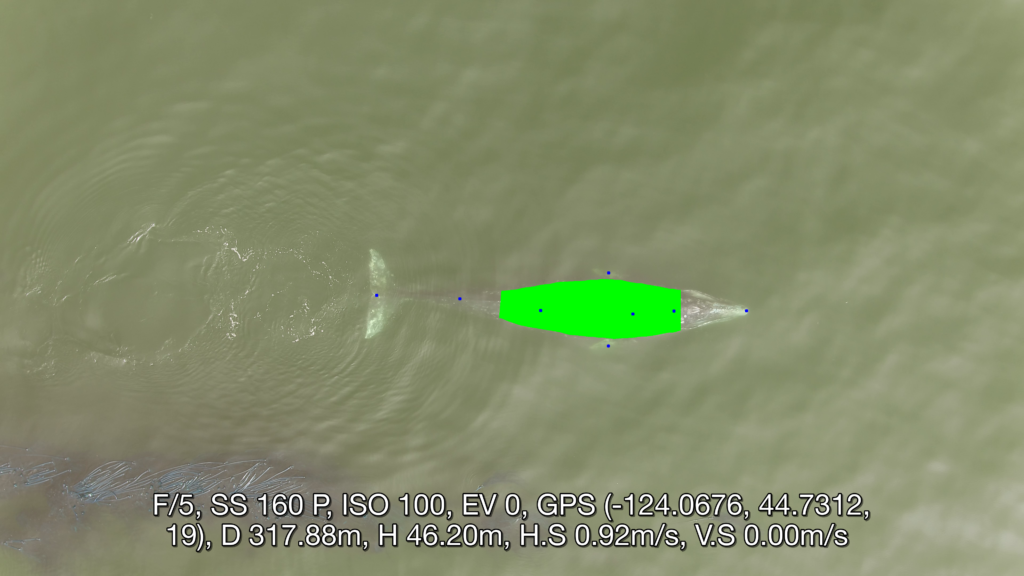

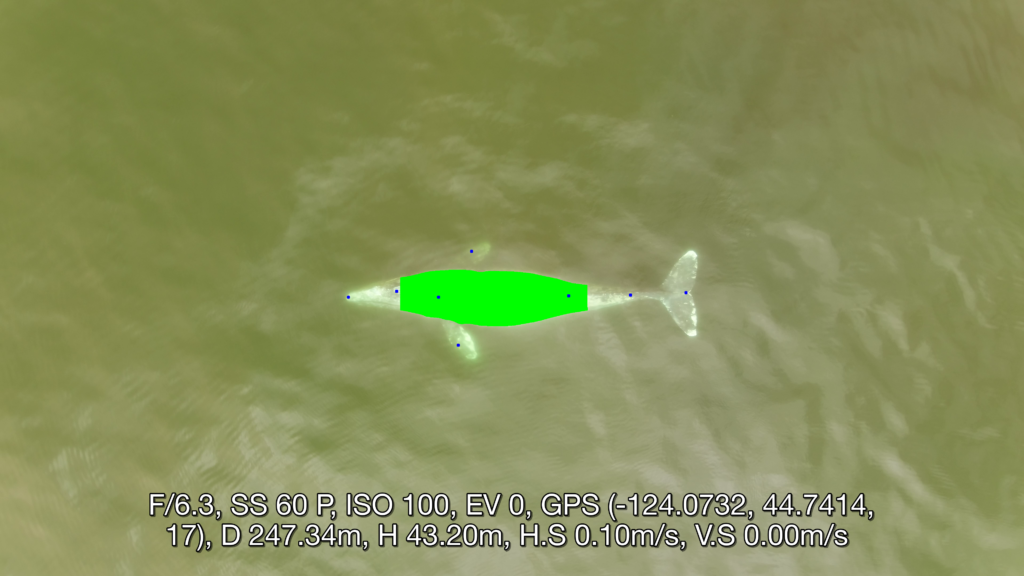

Body size and shape reflect how an animal functions in their environment and can provide details on an individual’s current health, reproductive status, and energetic requirements. Understanding how animals grow is a key component for monitoring the health of populations and their vulnerability to climate change and other stressors in their environment. As such, collecting accurate morphological measurements of individuals is essential to model growth and infer their health. Collecting such morphological measurements of whales is challenging, as you cannot ask a whale to hold still while you prepare the tape measure, but as discussed in a previous blog, drones provide a non-invasive method to collect body size measurements of whales. Photogrammetry is a non-invasive technique used to obtain morphological measurements of animals from photographs. The GEMM Lab uses drone-based photogrammetry to obtain morphological measurements of PCFG gray whales, such as their body length, skull length (as snout-to-blowhole), and fluke span (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Morphological measurements obtained via photogrammetry of a Pacific Coast Feeding Group (PCFG) gray whale. These measurements were used to compare to individuals from the Eastern North Pacific (ENP) population.

As mentioned in this previous blog, we use photo-identification to identify unique individual gray whales based on markings on their body. This method is helpful for linking all the data we are collecting (morphology, hormones, behavior, new scarring and skin conditions, etc.) to each individual whale. An individual’s sightings history can also be used to estimate their age, either as a ‘minimum age’ based on the date of first sighting or a ‘known age’ if the individual was seen as a calf. By combining the length measurements from drone-based photogrammetry and age estimates from photo-identification history, we can construct length-at-age growth models to examine how PCFG gray whales grow. While no study has previously examined length-at-age growth models specifically for PCFG gray whales, another study constructed growth curves for ENP gray whales using body length and age estimates obtained from whaling, strandings, and aerial photogrammetry (Agbayani et al., 2020). For our study, we utilized these datasets and compared length-at-age growth, snout-to-blowhole length, and fluke span between PCFG and ENP whales. We used Bayesian statistics to account and incorporate the various levels of uncertainty associated with data collected (i.e., measurements from whaling vs. drone, ‘minimum age’ vs. ‘known age’).

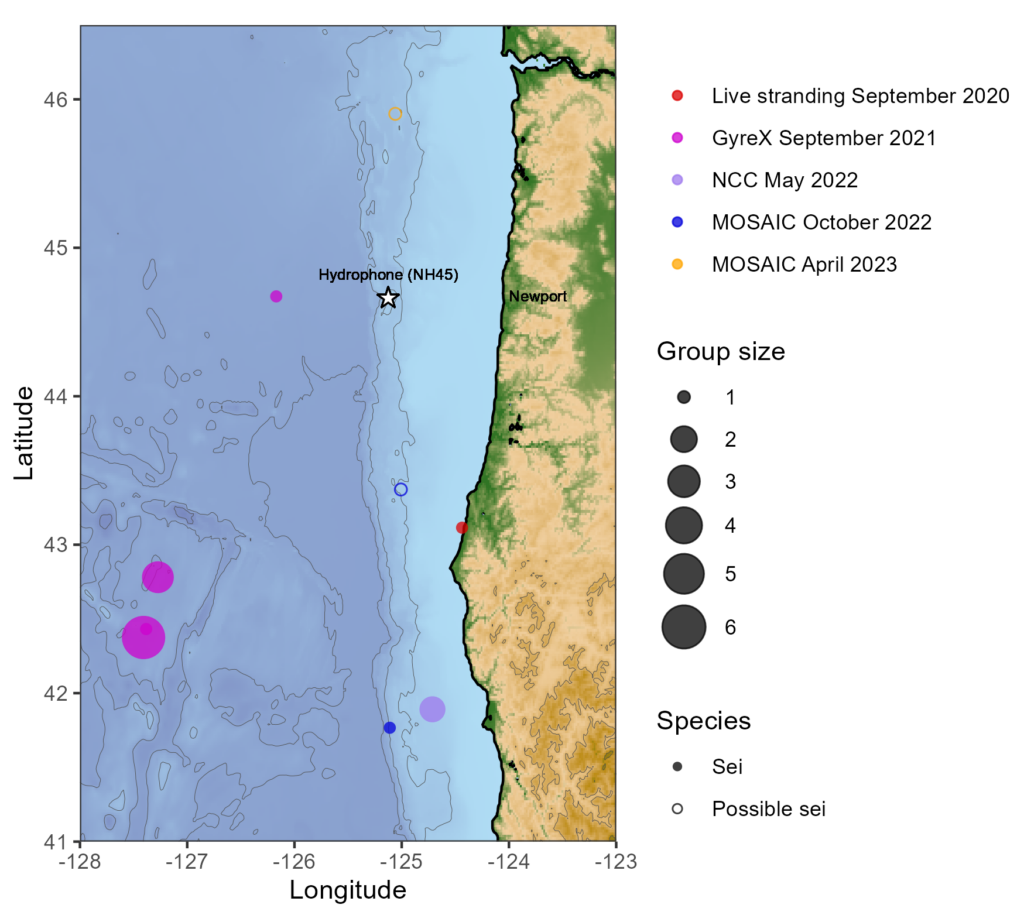

We found that while both populations grow at similar rates, PCFG gray whales reach smaller adult lengths than ENP. This difference was more extreme for females, where PCFG females were ~1 m (~3 ft) shorter than ENP females and PCFG males were ~0.5 m (1.5 ft) shorter than ENP males (Figure 2, Figure 3). We also found that ENP males and females have slightly larger skulls and flukes than PCFG male and females, respectively. Our results suggest PCFG whales are shaped differently than ENP whales (Figure 3)! These results are also interesting in light of our previous published study that found PCFG whales are skinnier than ENP whales (see this previous blog post).

Figure 2. Growth curves (von Bertalanffy–Putter) for length-at-age comparing male and female ENP and PCFG gray whales (shading represents 95% highest posterior density intervals). Points represent mean length and median age. Vertical bars represent photogrammetric uncertainty. Dashed horizontal lines represent uncertainty in age estimates.

Figure 3. Schematic highlighting the differences in body size between Pacific Coast Feeding Group (PCFG) and Eastern North Pacific (ENP) gray whales.

Our results raise some interesting questions regarding why PCFG are smaller: Is this difference in size and shape normal for this population and are they healthy? Or is this difference a sign that they are stressed, unhealthy and/or not getting enough to eat? Larger individuals are typically found at higher latitudes (this pattern is called Bergmann’s Rule), which could explain why ENP whales are larger since they feed in the Arctic. Yet many species, including fish, birds, reptiles, and mammals, have experienced reductions in body size due to changes in habitat and anthropogenic stressors (Gardner et al., 2011). The PCFG range is within closer proximity to major population centers compared to the ENP foraging grounds in the Arctic, which could plausibly cause increased stress levels, leading to decreased growth.

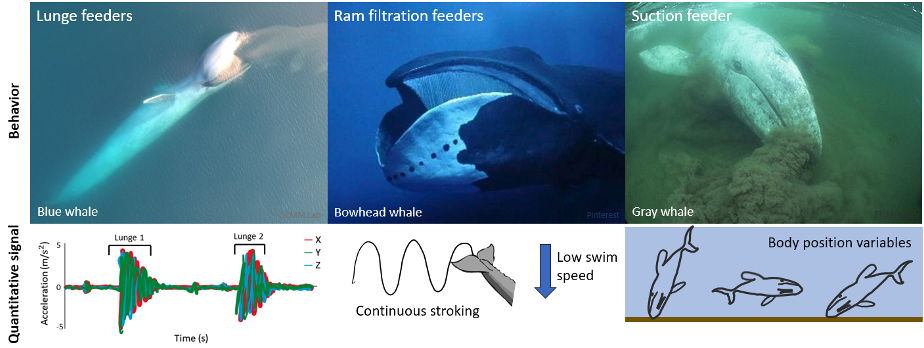

The smaller morphology of PCFG may also be related to the different foraging tactics they employ on different prey and habitat types than ENP whales. Animal morphology is linked to behavior and habitat (see this blogpost). ENP whales feeding in the Arctic generally forage on benthic amphipods, while PCFG whales switch between benthic, epibenthic and planktonic prey, but mostly target epibenthic mysids. Within the PCFG range, gray whales often forage in rocky kelp beds close to shore in shallow water depths (approx. 10 m) that are on average four times shallower than whales feeding in the Arctic. The prey in the PCFG range is also found to be of equal or higher caloric value than prey in the Arctic range (see this blog), which is interesting since PCFG were found to be skinnier.

It is also unclear when the PCFG formed? ENP and PCFG whales are genetically similar, but photo-identification history reveals that calves born into the PCFG usually return to forage in this PCFG range, suggesting matrilineal site fidelity that contributes to the population structure. PCFG whales were first documented off our Oregon Coast in the 1970s (Figure 4). Though, from examining old whaling records, there may have been PCFG gray whales foraging off the coasts of Northern California to British Columbia since the 1920s.

Figure 4. First reports of summer-resident gray whales along the Oregon coast, likely part of the Pacific Coast Feeding Group. Capital Journal, August 9, 1976, pg. 2.

Altogether, our finding led us to two hypotheses: 1) the PCFG range provides an ecological opportunity for smaller whales to feed on a different prey type in a shallow environment, or 2) the PCFG range is an ecological trap, where individuals gain less energy due to energetically costly feeding behaviors in complex habitat while potentially targeting lower density prey, causing them to be skinnier and have decreased growth. Key questions remain for our research team regarding potential consequences of the smaller sized PCFG whales, such as does the smaller body size equate to reduced resilience to environmental and anthropogenic stressors? Does smaller size effect fecundity and population fitness? Stay tuned as we learn more about this unique and fascinating smaller sized gray whale.

References

Agbayani, S., Fortune, S. M. E., & Trites, A. W. (2020). Growth and development of North Pacific gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus). Journal of Mammalogy, 101(3), 742–754. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyaa028

Bierlich, K. C., Kane, A., Hildebrand, L., Bird, C. N., Fernandez Ajo, A., Stewart, J. D., Hewitt, J., Hildebrand, I., Sumich, J., & Torres, L. G. (2023). Downsized: gray whales using an alternative foraging ground have smaller morphology. Biology Letters, 19(8). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2023.0043

Gardner, J. L., Peters, A., Kearney, M. R., Joseph, L., & Heinsohn, R. (2011). Declining body size: A third universal response to warming? Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 26(6), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2011.03.005