By Nicole Principe, first-year PhD student, OSU Dept of Fisheries, Wildlife and Conservation Sciences, GEMM Lab

Humans rely on oceans and coastal ecosystems for a variety of resources, such as tourism and recreation, fishing and aquaculture, transport of goods, and resource extraction. However, each use is contributing to new and cumulative stressors that are impacting marine mammals. The health of marine mammal populations can often serve as indicators of overall environmental health. Therefore, studying the stressors they face can help provide insights into the broader impacts on marine ecosystems and determine if conservation or management measures are necessary. As a master’s student at the College of Charleston in South Carolina and subsequently the stranding and research technician with the Lowcountry Marine Mammal Network (LMMN), I saw first-hand how some of these stressors affect local marine mammal populations.

In my role as the stranding and research technician with LMMN, I led the response and recovery of all deceased marine mammals, mainly bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops erebennus), in South Carolina to determine cause of death and identify main sources of mortality. Threats to these cetaceans can be environmental or anthropogenic in origin. Carefully examining and sampling every individual during a necropsy was critical to determine the presence of infectious disease, the contaminant and microplastic load, and any sign human interaction. While deaths from environmental causes can be more challenging for humans to mitigate, direct threats from human activity can be lessened with conservation actions and increased education to the public. LMMN responds to several strandings of dolphins each year that are the result of entanglement or boat strike. South Carolina has one of the highest rates of crab pot entanglements. In some cases, the call came quick enough that a disentanglement was possible, but in others, we found the animal already deceased with rope and gear still attached. Hundreds, if not thousands, of commercial and recreational crab pots are deployed within South Carolina estuaries, yet there are currently no regulations in place to help mitigate the threat of entanglement.

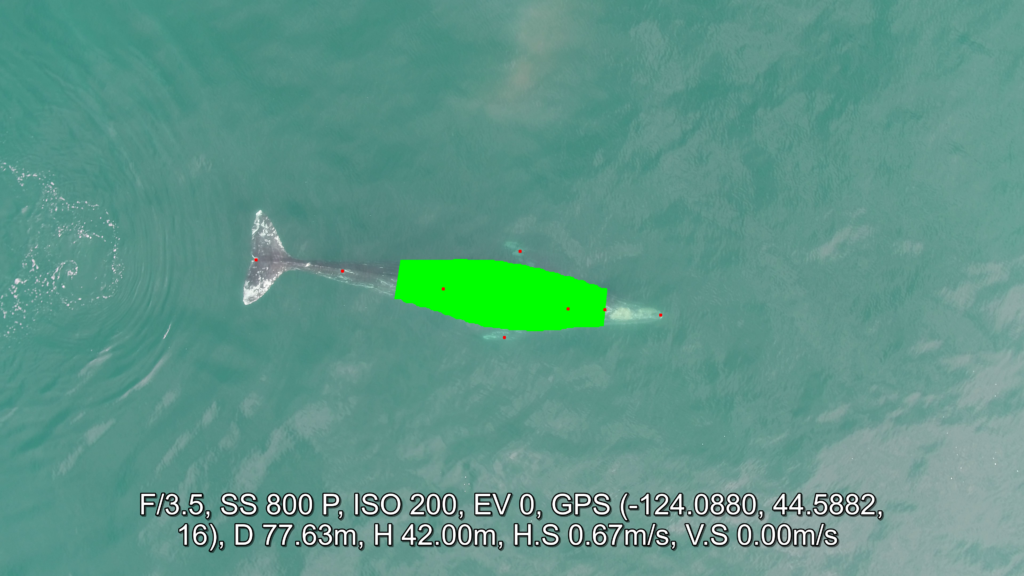

LMMN also conducts land and boat-based surveys to better understand strand feeding, which is a unique foraging strategy utilized by a small number of dolphins in South Carolina. When dolphins strand feed, they herd and trap fish up onto mudbanks or shorelines. The dolphins chase after the fish, briefly stranding themselves as they try to catch them. It is an incredible behavior to witness and because of this, it has become highly publicized as a tourist activity. There are areas where the public can walk right up as dolphins are attempting to hunt and many instances of people trying to touch, feed, or otherwise harass the dolphins have been reported. I also conducted a small study where I used drones to identify human interferences towards dolphins strand feeding and found that boaters and kayakers were often approaching the animals too closely, following them, or speeding through the inlet when animals were present. The write up on that project can be found here. High levels of human disturbance towards dolphins strand feeding could lead individuals to abandon otherwise suitable habitat, causing them to expend more energy to look for food elsewhere.

To help mitigate threats to dolphins from entanglements, boat strikes, and illegal harassment, the LMMN team and I created an educational workshop called W.A.V.E., which stands for Wildlife Awareness and Viewing Etiquette. These half-day workshops are tailored to both recreational boaters/public and commercial tour operators and fishermen and cover topics ranging from the importance of marine mammals in our ecosystem, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, global and local threats, and ways we can view marine wildlife that reduce disturbance. It is my hope that with more education and awareness about how humans use our waterways and interact with wildlife in negative ways, it can lead to positive changes. For more information about LMMN’s W.A.V.E. Workshops, head to their website.

In addition to cumulative stressors from human interactions, I also began to contemplate the role of climate change as a threat to the lives of marine mammals during my master’s research on dolphin distribution within the Charleston Estuary System (CES). A main question I was investigating was if and why some dolphins travel into low salinity waters high in the estuarine system. Bottlenose dolphins have evolved in marine and estuarine environments where salinity levels are typically ~30 parts per thousand (ppt). While dolphins can withstand short durations of exposure to low salinity (defined as 15 ppt), prolonged exposure to freshwater can result in negative health consequences, such as sloughing of skin and ulcerative lesions, changes in pathophysiology, and eventual mortality (Ewing et al., 2017). Over the past 20 years, many intermittent dolphin sightings and strandings occurred in riverine areas of the CES where salinity levels were below 10 ppt. To better understand how and why dolphins use this risky habitat, I conducted drone surveys across the CES for a year. I did find dolphin groups traveling and feeding in low salinity waters, however, the encounters were only during months with warmer water temperatures (Principe et al., 2023). We hypothesize that environmental conditions during those months may lead to decreased prey availability in the lower, more suitable parts of the estuary, forcing dolphins to travel further up the rivers to access higher abundances of prey (especially mullet). Other studies in different regions have found similar results of dolphins traveling into low salinity water during warmer months potentially in response to prey (Mintzer and Fazioli, 2021; Takeshita et al., 2021).

These results lead to questions as to how prey and dolphin movements will shift under future climate change scenarios. Increasing warm water temperatures may lead to further shifts in prey distribution, potentially driving more estuarine dolphins to utilize upper riverine habitats to find food. Just since 2022, four dolphins were observed in freshwater habitat for several weeks. Two were eventually found and confirmed deceased and two went missing and are presumed deceased. If more dolphins use and remain in these low salinity habitats for extended periods, negative health consequences could lead to population impacts and signal a need for more conservation and management actions.

It is quickly becoming evident that climate change is threatening marine mammals, at both local and global scales. More research is needed to better understand how changing environmental conditions is impacting the availability and quality of prey and how large marine predators are shifting in response. For my PhD, I am working with the GEMM Lab on the SAPPHIRE (Synthesis of Acoustics, Physiology, Prey, and Habitat in a Rapidly changing Environment) project, where we are researching how changing ocean conditions affect the availability of krill, and blue whale behavior, health, and reproduction in New Zealand. The South Taranaki Bight (STB) region experiences a productive coastal upwelling system that supports enhanced primary productivity (Chiswell et al. 2017) and dense aggregations of prey (Bradford-Grieve et al., 1993). Pygmy blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus brevicauda) in this region are not known to migrate and instead use the STB region year-round for foraging and reproduction (Torres, 2013; Barlow et al., 2022). After a marine heatwave in the Tasman Sea in 2015-2016, there were less krill aggregations due to lessened upwelling (Barlow et al., 2020), which caused reduced foraging effort, and subsequently reduced reproductive activity by blue whales (Barlow et al. 2023). Continued field work and data analysis will help us to develop Species Health Models that will predict how these prey and predator populations will respond to future environmental change.

Overall, it is clear that human activity is leading to direct and indirect impacts on marine mammal populations at many different scales, from an individual human harassing a foraging dolphin to global climate change impacts on blue whale population dynamics. Ongoing research is essential in understanding these impacts better and thus inform development of effective conservation strategies to protect both marine mammals and the environment.

References

Barlow DR, Bernard KS, Escobar-Flores P, Palacios DM, Torres LG (2020) Links in the trophic chain: Modeling functional relationships between in situ oceanography, krill, and blue whale distribution under different oceanographic regimes. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 642:207–225.

Barlow DR, Klinck H, Ponirakis D, Branch TA, Torres LG (2023) Environmental conditions and marine heatwaves influence blue whale foraging and reproductive effort. Ecol Evol 13:e9770.

Barlow DR, Klinck H, Ponirakis D, Holt Colberg M, Torres LG (2022) Temporal occurrence of three blue whale populations in New Zealand waters from passive acoustic monitoring. J Mammal 104(1): 29–38.

Bradford-Grieve JM, Murdoch RC, Chapman BE (1993) Composition of macrozooplankton assemblages associated with the formation and decay of pulses within an upwelling plume in greater cook strait, New Zealand. New Zeal J Mar Freshw Res 27(1): 1–22.

Chiswell SM, Zeldis JR, Hadfield MG, Pinkerton MH (2017) Wind-driven upwelling and surface chlorophyll blooms in greater Cook Strait. New Zeal J Mar Fresw Res 51(4): 465–489.

Ewing RY, Mase-Guthrie B, McFee W, Townsend F, Manire CA, Walsh M,

Borkowski R, Bossart GD, Schaefer AM (2017). Evaluation of serum for pathophysiological effects of prolonged low salinity water exposure in displaced bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). Front Vet Sci 4

Hornsby F, McDonald T, Balmer BC, Speakman T, Mullin K, Rosel P, Wells R, Telander A, Marcy P, Schwacke L (2017) Using salinity to identify common bottlenose dolphin habitat in Barataria Bay, Louisiana, USA. Endanger Species Res 33: 833–192.

Mintzer VJ, Fazioli KL (2021) Salinity and water temperature as predictors of bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) encounter rates in upper Galveston Bay, Texas. Front Mar Sci 8

Principe N, McFee W, Levine N, Balmer B, Ballenger J (2023). Using Unoccupied Aerial Systems (UAS) to Determine the Distribution Patterns of Tamanend’s Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops erebennus) across Varying Salinities in Charleston, South Carolina. Drones 7(12): 10.3390/drones7120689.

Takeshita R, Balmer BC, Messina F, Zolman ES, Thomas L, Wells RS, Smith CR, Rowles TK, Schwacke LH (2021). High site-fidelity in common bottlenose dolphins despite low salinity exposure and associated indicators of compromised health. PLoS ONE, 16(9), e0258031.

Torres LG (2013) Evidence for an unrecognised blue whale foraging ground in New Zealand. New Zeal J Mar Freshw Res 47:235–248.