Lindsay Wickman, Postdoctoral Scholar, Oregon State University Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

This summer, Rep. Nick Begich of (R-AK), submitted a draft bill that proposes to roll back key features of the 1972 U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA). The MMPA has been the centerpiece legislation protecting whales, dolphins, sea otters, manatees, polar bears and seals for over 50 years, bringing many species back from the brink of extinction and setting a benchmark that has been replicated worldwide. Among the changes proposed, the draft bill explicitly bars the use of the precautionary principle in marine mammal management. For example, the draft bill includes these changes:

- changing wording from “has the potential to injure/disturb” to “injures or disturbs” when considering threats that need to be mitigated.

- instead of managing marine mammal populations to “result in maximum productivity”, the draft bill would manage species at the size “necessary to support the continued survival”.

The draft bill also includes changes to how allowable levels of injury and mortality to marine mammal populations (called a “take”) in the MMPA are calculated. Until now, these take levels were calculated using safety factors that correct for scientific uncertainty and bias. The proposal removes these safety factors, which would essentially increase the number of allowable takes from each population before management intervention is required. The proposed changes also require a much higher burden of proof before populations can be considered “depleted” or “strategic”, which are identifiers that trigger conservation action.

Proponents of the draft bill say the current MMPA has been too precautionary, unnecessarily increasing burdens on fishers and other resource users. Here, I argue that the precautionary principle is not a subjective judgement that favors marine mammals over people’s livelihoods. Instead, it is a rational decision-making tool, essential for making management decisions when information is uncertain.

What is the precautionary principle?

In practice, it means that a lack of data or uncertainty in statistical estimates or trends should not be used as an excuse for inaction in the face of a valid threat (Raffensperger and Tickner, 1999). Instead, decision-makers should incorporate “safety factors” that account for limited knowledge or imperfect science. As said by Holt and Talbot (1978), “the magnitude of the safety factor should be proportional to the magnitude of risk.” So, if the goal is to prevent extinction, severely depleted populations may require bigger safety factors than healthy populations.

How does the U.S. MMPA apply the precautionary principle?

During the first few decades the MMPA, actions to protect marine mammals were primarily reactionary, in response to highly publicized issues like the dolphin-tuna problem (Taylor et al., 2000). Conservation actions were supposed to be triggered when scientists detected a declining trend in a population’s abundance, but obtaining precise estimates of population size is notoriously difficult for marine mammals. The amount of data required to prove a population was declining due to human activities was so high that protection was continually stalled due to uncertainty in statistical trends (e.g., Marine Mammal Commission 1982; Wade 1993; Taylor et al., 2000).

In 1994, the U.S. MMPA was amended, implementing a new way to determine which marine mammal populations were at risk. Instead of requiring a statistical trend in population abundance, the new method calculates the number of sustainable takes without putting the population at risk of decline. The 1994 amendments also explicitly applied the precautionary principle by incorporating safety factors into this calculation of this number of allowable takes, known as the Potential Biological Removal (PBR; Wade 1998), which increases the likelihood that the management goals stated by the MMPA are achieved (Taylor et al., 2000).

Three reasons why the precautionary principle matters:

1. It accounts for uncertainty and potential bias

Consider air travel for a moment: Given the uncertainty in the amount of time it takes to arrive at the airport (e.g., traffic, parking) and the unknown possibilities for extra delays once there (e.g., security), most travelers shoot for airport arrival times significantly earlier than the flight boards. However, what if instead of an exact flight time, you are told the plane leaves sometime between 9 and 11 am? Also, although you have some experience travelling, you have never used this particular airport, and you have no idea how long security and check-in might take. Given these hypothetical circumstances, how would you plan your travel?

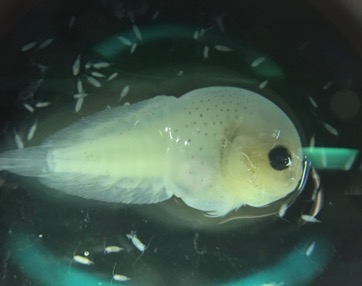

When applying marine mammal science to management goals, decision-makers must contend with a similarly uncertain set of information. Marine mammals are wide-ranging and spend most of their lives underwater, making them particularly challenging to study. It is impossible to get exact estimates of population size for these animals, and even the best designed research produces abundance estimates with significant levels uncertainty (e.g., Taylor et al., 2000; Taylor et al. 2007). After decades of researching marine mammals, we also still have significant knowledge gaps about their population dynamics, space-use, and behaviors.

Currently, the MMPA accounts for scientific uncertainty by using minimum estimated population size (the lower 20th percentile) when calculating sustainable levels of human takes (Wade 1998; Taylor et al. 2000). This safety factor makes it more likely that calculations of allowable takes are at or below safe levels (Wade 1998; Taylor et al. 2000).

Relating back to the airport example, if you were told your flight could leave between 9 and 11 am, using minimum population size (instead of the maximum or center of the estimate) is analogous to planning for the flight to leave closer to 9 am. However, you still need to add in time for extra factors that may cause other possible delays in addition to the uncertain departure time.

So, in addition to minimum population size, the MMPA also uses another safety factor in its calculation of allowable takes, called the recovery factor (FR). FR scales the number of allowable takes relative to the level of risk to the population and the potential for biased or uncertain information (Wade 1998; Taylor et al. 2000). A lower FR is given to depleted, high risk populations, while FR can be increased for well-studied populations at lower risk (Wade 1998; Taylor et al. 2000). In the travel analogy, FR is the amount of padding needed to ensure a passenger makes their flight, accounting for potentially unknown security lines and traffic.

2. It incentivizes the public and industry to collect more data to “fine-tune” management

The more experienced you are with a particular airport and the more certain you are of the departure time, the more confident you can be in your travel plans. If you know the plane leaves at 10 am, and security takes 15 minutes, you don’t need to add nearly as much extra travel time as if your travel details were more uncertain.

Importantly, as the scientific knowledge of a population increases, the magnitude of the safety factors in the calculation of allowable mortalities decreases. For example, as the number of surveys of a population increases and an abundance estimate gets more precise, the range of the abundance estimate gets smaller. So, getting a more precise abundance estimate is like changing your uncertain flight time from being between 9 – 11 am, to being between 9:30 – 10 am. While you still have some uncertainty, you can be confident that leaving a little later than originally planned would be ok.

Since better knowledge results in more targeted management, both the public and industry are motivated to invest in continued research. Fine-tuning management means that necessary precautions can be kept, but unnecessary burdens on industries are removed. Ultimately, the strategy of a precautionary approach is to “act now, fine-tune later,” instead of “delay action until we get detailed information.” In addition to potentially delaying urgent action, the latter approach also disincentivizes industry to invest in research or develop solutions. As explained below, delaying conservation due to uncertainty has led to past pitfalls in marine mammal conservation, necessitating the need for a more proactive approach.

3. It prevents unnecessary delays in conservation action

If you had an important flight to catch on Wednesday, but did not know the departure time, would you decide to not go to the airport at all? Would it be worth it to just get to the airport early, or would you wait at home for more information, but at the risk of missing your flight?

The choice to not act at all in the face of uncertain data is inherently risky. For the first couple of decades of the MMPA, managers attempted to prove a population was declining before conservation action could be taken. The problem is, determining population trends of marine mammals with any certainty can take decades (Taylor and Gerrodette, 1993; Wade 1993; Taylor et al., 2000). In the case of some species, by the time scientists have the statistical power to detect a trend, the population could already be in a catastrophic decline. For example, in the case of eastern tropical Pacific dolphins killed as bycatch by the tuna industry during the 1970s, proving their population decline led to a 14-year protection delay from the first abundance estimate of the population (Wade et al., 1994; Taylor et al., 2000).

The purpose of the 1994 MMPA amendments was to correct for these unnecessary delays that required extensive amounts of data (Taylor et al. 2000). Instead of requiring population trend data, the MMPA now uses values that are much easier to obtain — population size and maximum population growth rates (Wade 1998). From these, the number of individuals that can sustainably be removed from the population (PBR) can be calculated. This approach is a much faster and simpler method, allowing for quick action if estimated mortality (e.g., numbers of animals killed or injured) is higher than this calculated threshold (PBR).

Lastly, the precautionary principle assumes that if a threat is valid, it should be considered, even if the effects are not 100% proven yet. This approach is essential for marine mammals, where anthropogenic injuries and mortality are not always easily detected or recorded. In the case of ship strikes and fisheries entanglement, many individuals disappear before their deaths or injuries are recorded (e.g., Cassoff et al., 2011; Pace et al. 2021). Other threats, like the effects of sound and chemical pollution, may require long-term monitoring to fully understand their population-level impacts. By using language like “has the potential to injure,” management can be implemented more proactively, allowing for research to continue, but not at the detriment of population health during the lengthy time it can take to establish statistical certainty.

Final thoughts

The precautionary principle is a way of dealing with the fact that good science can cost precious time. Results rarely give “yes or no” answers and clear-cut solutions. Instead, decision-makers must weigh study design, statistical power, and the precision (i.e., uncertainty) of scientific findings. The precautionary principle provides a framework for how to effectively use science to make decisions, increasing the likelihood that management plans meet their goals.

If this blog makes you concerned about the future of the precautionary principle in the U.S. MMPA:

- Write to your congressional representatives letting them know you oppose the draft bill.

- You can find contact information for your Congressional representatives here: https://www.congress.gov/members/find-your-member

Did you enjoy this blog? Want to learn more about marine life, research, and conservation? Subscribe to our blog and get a monthly message when we post a new blog. Just add your name and email into the subscribe box below.

References

Cassoff, R.M., Moore, K.M., McLellan, W.A., Barco, S.G., Rotstein, D.S., Moore, M.J. (2011). Lethal entanglement in baleen whales. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 96: 175– 185.

Holt, S. J., and L. M. Talbot. (1978). New principles for the conservation of wild living resources. Wildlife Monographs, 59.

Marine Mammal Commission. (1982). Marine Mammal Commission annual report to Congress. Bethesda, Maryland.

Pace, R.M., Williams, R., Kraus, S.D., Knowlton, A.R., Pettis, H.M. (2021). Cryptic mortality of North Atlantic right whales. Conservation Science and Practice, 3: e346.

Raffensperger C, Tickner J, eds. (1999). Protecting Public Health and the Environment: Implementing the Precautionary Principle. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Taylor, B. L., & Gerrodette, T. (1993). The Uses of Statistical Power in Conservation Biology: The Vaquita and Northern Spotted Owl. Conservation Biology, 7(3), 489–500.

Taylor, B. L., Wade, P. R., de Master, D. P., & Barlow, J. (2000). Incorporating uncertainty into management models for marine mammals. Conservation Biology, 14(5), 1243–1252.

Taylor, B. L., Martinez, M., Gerrodette, T., Barlow, J., & Hrovat, Y. N. (2007). Lessons From Monitoring Trends in Abundance of Marine Mammals. Marine Mammal Science, 23(1), 157–175.

Wade, P. R. (1993). Estimation of historical population size of the eastern spinner dolphin (Stenella longirostris orientalis). Fishery Bulletin, United States 91:775–787.

Wade, P. R. (1994). Abundance and population dynamics of two eastern Pacific dolphins, Stenella attenuata and Stenella longirostris orientalis. Ph.D. dissertation. Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego.

Wade, P. R. (1998). Calculating limits to the allowable human-caused mortality of cetaceans and pinnipeds. Marine Mammal Science, 14(1), 1–37.