By Dawn Barlow1 and Will Kennerley2

1PhD Candidate, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

2MS Student, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences, Seabird Oceanography Lab

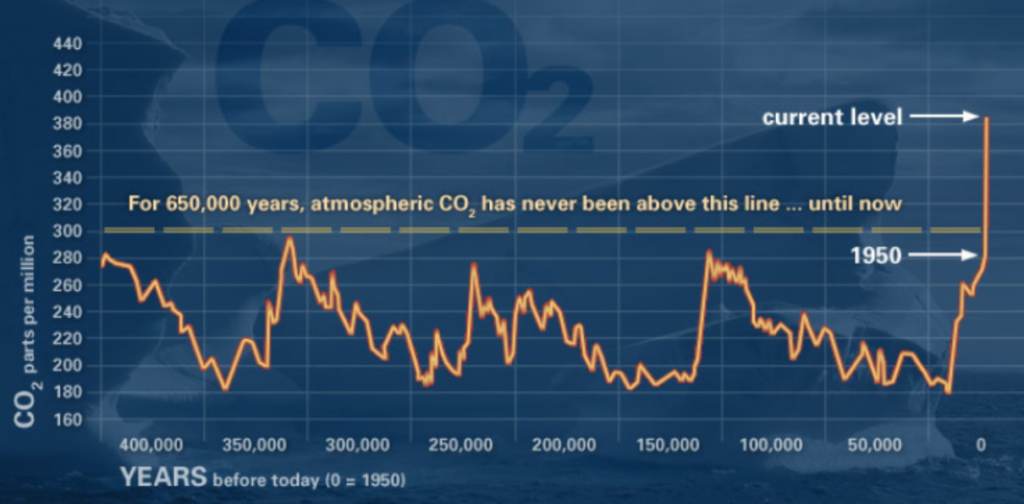

The marine environment is dynamic, and mobile animals must respond to the patchy and ephemeral availability of resource in order to make a living (Hyrenbach et al. 2000). Climate change is making ocean ecosystems increasingly unstable, yet these novel conditions can be difficult to document given the vast depth and remoteness of most ocean locations. Marine megafauna species such as marine mammals and seabirds integrate ecological processes that are often difficult to observe directly, by shifting patterns in their distribution, behavior, physiology, and life history in response to changes in their environment (Croll et al. 1998, Hazen et al. 2019). These mobile marine animals now face additional challenges as rising temperatures due to global climate change impact marine ecosystems worldwide (Hazen et al. 2013, Sydeman et al. 2015, Silber et al. 2017, Becker et al. 2019). Given their mobility, visibility, and integration of ocean processes across spatial and temporal scales, these marine predator species have earned the reputation as effective ecosystem sentinels. As sentinels, they have the capacity to shed light on ecosystem function, identify risks to human health, and even predict future changes (Hazen et al. 2019). So, let’s explore a few examples of how studying marine megafauna has revealed important new insights, pointing toward the importance of monitoring these sentinels in a rapidly changing ocean.

Cairns (1988) is often credited as first promoting seabirds as ecosystem sentinels and noted several key reasons why they were perfect for this role: (1) Seabirds are abundant, wide-ranging, and conspicuous, (2) although they feed at sea, they must return to land to nest, allowing easier observation and quantification of demographic responses, often at a fraction of the cost of traditional, ship-based oceanographic surveys, and therefore (3) parameters such as seabird reproductive success or activity budgets may respond to changing environmental conditions and provide researchers with metrics by which to assess the current state of that ecosystem.

The unprecedented 2014-2016 North Pacific marine heatwave (“the Blob”) caused extreme ecosystem disruption over an immense swath of the ocean (Cavole et al. 2016). Seabirds offered an effective and morbid indication of the scale of this disruption: Common murres (Uria aalge), an abundant and widespread fish-eating seabird, experienced widespread breeding failure across the North Pacific. Poor reproductive performance suggested that there may have been fewer small forage fish around and that these changes occurred at a large geographic scale. The Blob reached such an extreme as to kill immense numbers of adult birds, which professional and community scientists found washed up on beach-surveys; researchers estimate that an incredible 1,200,000 murres may have died from starvation during this period (Piatt et al. 2020). While the average person along the Northeast Pacific Coast during this time likely didn’t notice any dramatic difference in the ocean, seabirds were shouting at us that something was terribly wrong.

Happily, living seabirds also act as superb ecosystem sentinels. Long-term research in the Gulf of Maine by U.S. and Canadian scientists monitors the prey species provisioned by adult seabirds to their chicks. Will has spent countless hours over five summers helping to conduct this research by watching terns (Sterna spp.) and Atlantic puffins (Fratercula arctica) bring food to their young on small islands off the Maine coast. After doing this work for multiple years, it’s easy to notice that what adults feed their chicks varies from year to year. It was soon realized that these data could offer insight into oceanographic conditions and could even help managers assess the size of regional fish stocks. One of the dominant prey species in this region is Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus), which also happens to be the focus of an economically important fishery. While the fishery targets four or five-year-old adult herring, the seabirds target smaller, younger herring. By looking at the relative amounts and sizes of young herring collected by these seabirds in the Gulf of Maine, these data can help predict herring recruitment and the relative number of adult herring that may be available to fishers several years in the future (Scopel et al. 2018). With some continued modelling, the work that we do on a seabird colony in Maine with just a pair of binoculars can support or maybe even replace at least some of the expensive ship-based trawl surveys that are now a popular means of assessing fish stocks.

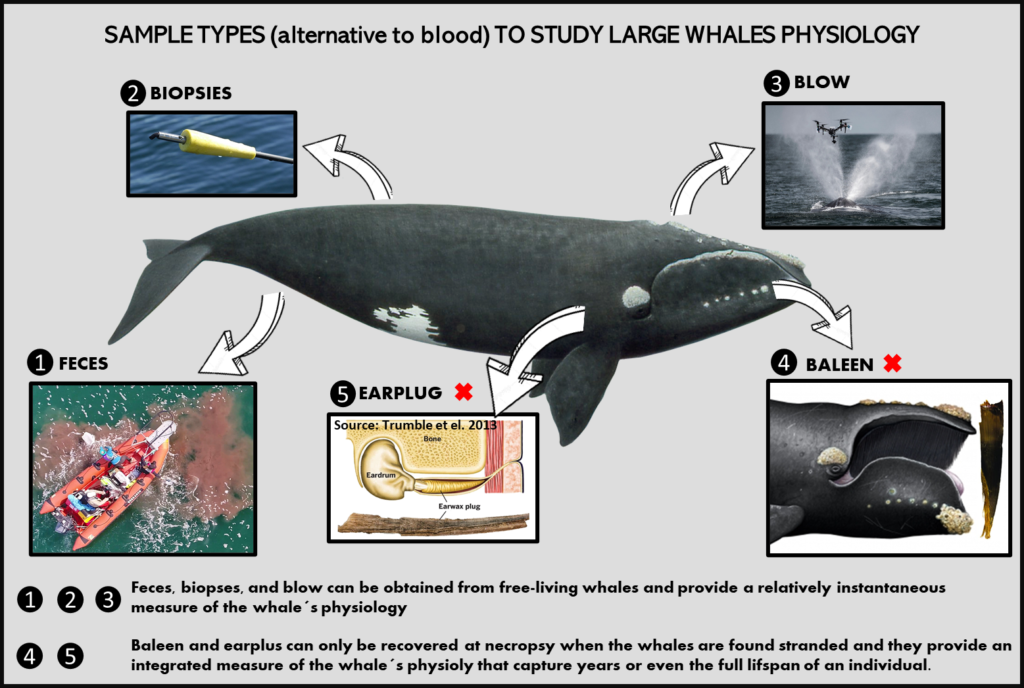

For more far-ranging and inaccessible marine predators such as whales, measuring things such as dietary shifts can be more challenging than it is for seabirds. Nevertheless, whales are valuable ecosystem sentinels as well. Changes in the distribution and migration phenology of specialist foragers such as blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) and North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) can indicate relative changes in the distribution and abundance of their zooplankton prey and underlying ocean conditions (Hazen et al. 2019). In the case of the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale, their recent declines in reproductive success reflect a broader regime shift in climate and ocean conditions. Reduced copepod prey has resulted in fewer foraging opportunities and changing foraging grounds, which may be insufficient for whales to obtain necessary energetic stores to support calving (Gavrilchuk et al. 2021, Meyer-Gutbrod et al. 2021). These whales assimilate and showcase the broad-scale impacts of climate change on the ecosystem they inhabit.

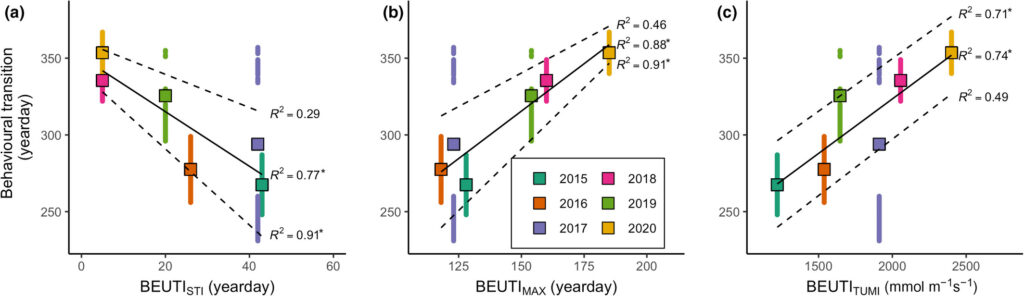

Blue whales that feed in the rich upwelling system off the coast of California rely on the availability of their krill prey to support the population (Croll et al. 2005). A recent study used acoustic monitoring of blue whale song to examine the timing of annual population-level transition from foraging to breeding migration compared to oceanographic variation, and found that flexibility in timing may be a key adaptation to persistence of this endangered population facing pressures of rapid environmental change (Oestreich et al. 2022). Specifically, blue whales delayed the transition from foraging to breeding migration in years of the highest and most persistent biological productivity from upwelling, and therefore listening to the vocalizations of these whales may be valuable indicator of the state of productivity in the ecosystem.

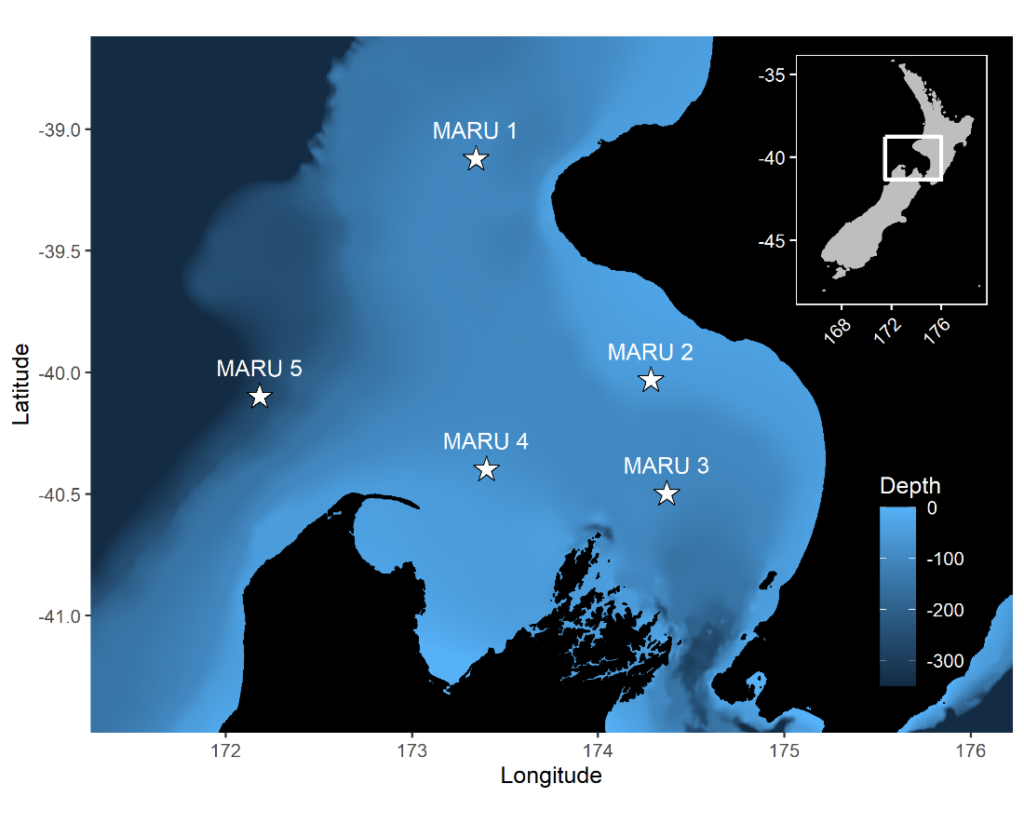

In a similar vein, research by the GEMM Lab on blue whale ecology in New Zealand has linked their vocalizations known as D calls to upwelling conditions, demonstrating that these calls likely reflect blue whale foraging opportunities (Barlow et al. 2021). In ongoing analyses, we are finding that these foraging-related calls were drastically reduced during marine heatwave conditions, which we know altered blue whale distribution in the region (Barlow et al. 2020). Now, for the final component of Dawn’s PhD, she is linking year-round environmental conditions to the occurrence patterns of different blue whale vocalization types, hoping to shed light on ecosystem processes by listening to the signals of these ecosystem sentinels.

It is important to understand the widespread implications of the rapidly warming climate and changing ocean conditions on valuable and vulnerable marine ecosystems. The cases explored here in this blog exemplify the importance of monitoring these marine megafauna sentinel species, both now and into the future, as they reflect the health of the ecosystems they inhabit.

Did you enjoy this blog? Want to learn more about marine life, research and conservation? Subscribe to our blog and get a weekly email when we make a new post! Just add your name into the subscribe box on the left panel.

References:

Barlow DR, Bernard KS, Escobar-Flores P, Palacios DM, Torres LG (2020) Links in the trophic chain: Modeling functional relationships between in situ oceanography, krill, and blue whale distribution under different oceanographic regimes. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 642:207–225.

Barlow DR, Klinck H, Ponirakis D, Garvey C, Torres LG (2021) Temporal and spatial lags between wind, coastal upwelling, and blue whale occurrence. Sci Rep 11:1–10.

Becker EA, Forney KA, Redfern J V., Barlow J, Jacox MG, Roberts JJ, Palacios DM (2019) Predicting cetacean abundance and distribution in a changing climate. Divers Distrib 25:626–643.

Cairns DK (1988) Seabirds as indicators of marine food supplies. Biol Oceanogr 5:261–271.

Cavole LM, Demko AM, Diner RE, Giddings A, Koester I, Pagniello CMLS, Paulsen ML, Ramirez-Valdez A, Schwenck SM, Yen NK, Zill ME, Franks PJS (2016) Biological impacts of the 2013–2015 warm-water anomaly in the northeast Pacific: Winners, losers, and the future. Oceanography 29:273–285.

Croll DA, Marinovic B, Benson S, Chavez FP, Black N, Ternullo R, Tershy BR (2005) From wind to whales: Trophic links in a coastal upwelling system. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 289:117–130.

Croll DA, Tershy BR, Hewitt RP, Demer DA, Fiedler PC, Smith SE, Armstrong W, Popp JM, Kiekhefer T, Lopez VR, Urban J, Gendron D (1998) An integrated approch to the foraging ecology of marine birds and mammals. Deep Res Part II Top Stud Oceanogr.

Gavrilchuk K, Lesage V, Fortune SME, Trites AW, Plourde S (2021) Foraging habitat of North Atlantic right whales has declined in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Canada, and may be insufficient for successful reproduction. Endanger Species Res 44:113–136.

Hazen EL, Abrahms B, Brodie S, Carroll G, Jacox MG, Savoca MS, Scales KL, Sydeman WJ, Bograd SJ (2019) Marine top predators as climate and ecosystem sentinels. Front Ecol Environ 17:565–574.

Hazen EL, Jorgensen S, Rykaczewski RR, Bograd SJ, Foley DG, Jonsen ID, Shaffer SA, Dunne JP, Costa DP, Crowder LB, Block BA (2013) Predicted habitat shifts of Pacific top predators in a changing climate. Nat Clim Chang 3:234–238.

Hyrenbach KD, Forney KA, Dayton PK (2000) Marine protected areas and ocean basin management. Aquat Conserv Mar Freshw Ecosyst 10:437–458.

Meyer-Gutbrod EL, Greene CH, Davies KTA, Johns DG (2021) Ocean regime shift is driving collapse of the north atlantic right whale population. Oceanography 34:22–31.

Oestreich WK, Abrahms B, Mckenna MF, Goldbogen JA, Crowder LB, Ryan JP (2022) Acoustic signature reveals blue whales tune life history transitions to oceanographic conditions. Funct Ecol.

Piatt JF, Parrish JK, Renner HM, Schoen SK, Jones TT, Arimitsu ML, Kuletz KJ, Bodenstein B, Garcia-Reyes M, Duerr RS, Corcoran RM, Kaler RSA, McChesney J, Golightly RT, Coletti HA, Suryan RM, Burgess HK, Lindsey J, Lindquist K, Warzybok PM, Jahncke J, Roletto J, Sydeman WJ (2020) Extreme mortality and reproductive failure of common murres resulting from the northeast Pacific marine heatwave of 2014-2016. PLoS One 15:e0226087.

Scopel LC, Diamond AW, Kress SW, Hards AR, Shannon P (2018) Seabird diets as bioindicators of atlantic herring recruitment and stock size: A new tool for ecosystem-based fisheries management. Can J Fish Aquat Sci.

Silber GK, Lettrich MD, Thomas PO, Baker JD, Baumgartner M, Becker EA, Boveng P, Dick DM, Fiechter J, Forcada J, Forney KA, Griffis RB, Hare JA, Hobday AJ, Howell D, Laidre KL, Mantua N, Quakenbush L, Santora JA, Stafford KM, Spencer P, Stock C, Sydeman W, Van Houtan K, Waples RS (2017) Projecting marine mammal distribution in a changing climate. Front Mar Sci 4:413.

Sydeman WJ, Poloczanska E, Reed TE, Thompson SA (2015) Climate change and marine vertebrates. Science 350:772–777.