Dr. KC Bierlich, Postdoctoral Scholar, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, & Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna (GEMM) Lab

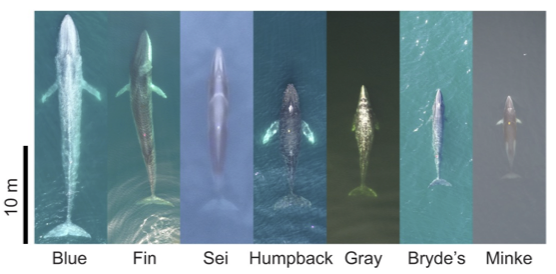

Baleen whales are known for their gigantism and encompass a wide range in body sizes extending from blue whales that are the largest animals to live on earth (max length ~30 m) to minke whales (max length ~10 m) that are the smallest of baleen whales (Fig. 1). While all baleen whales are filter feeders, a group called the rorquals use a feeding strategy known as lunge feeding (or intermittent engulfment filtration), which involves engulfing large volumes of prey-laden water at high speeds and then filtering the water out of their mouth using their baleen as a “sieve”. There is positive allometry associated with this feeding technique and body size, meaning that as whales are larger, this feeding strategy becomes more efficient due to increased engulfment of water volume per each lunge feeding event. In other words, a bigger body size equates to a much larger mouthful of food. For example, a minke whale (body length ~7-10 m) will engulf water volume equivalent to ~42% of its body mass, while a blue whale (~21-24 m) engulfs ~135%. Thus, filter feeding enables gigantism through efficient exploitation of large, dense patches of prey. An interesting question then arises: what is the minimum body size at which filter feeding is still efficient? Or in other words, why are the smallest of the baleen whales, minke whales, not smaller? For this blog, I will highlight a study published today in Nature Ecology and Evolution titled “Minke whale feeding rate limitations suggest constraints on the minimum body size for engulfment filtration feeding” led by friend and collaborator of the GEMM Lab Dr. Dave Cade and included myself and other collaborators as co-authors from Stanford University, UC Santa Cruz, Cascadia Research Collective, Duke University, and University of Queensland.

The largest animals of today are marine filter feeders, such as whale sharks, manta rays, and baleen whales, which all share parallel evolutionary histories in which their large body sizes and filter-feeding morphologies are derived from smaller-bodied ancestors that targeted single prey items. Changes in ocean productivity increased the concentrations of smaller prey in the oceans around 5 million years ago, enabling filter feeding as an efficient feeding strategy through capture of abundant aggregations of prey by filtering large volumes of water. It is interesting to note, that within these filter feeding lineages of animals, there are groups of animals that are single-prey foragers with smaller body sizes. For example, the whale shark is the only filter feeder amongst the carpet sharks and the manta ray is much larger than other rays that feed on single prey items. Amongst cetaceans, the smallest single-prey foragers, dolphins (~2-3 m) and porpoises (~1.4-1.9 m), are much smaller than the smallest of the filter feeding cetaceans, minke whales (~7-10 m). These common differences in body sizes and feeding strategies within lineages suggest that there may be minimum body size requirements for this filter feeding strategy to be efficient.

To investigate the limits on minimum body size for filter feeding, our study explored the foraging behavior of Antarctic minke whales, the smallest of the rorqual baleen whales, along the Western Antarctic Peninsula. Our team tagged a total of 23 individuals using non-invasive suction cup tags, like the ones we use for our tagging component in the GEMM Lab’s GRANITE project (see this blog for more details). One of my roles on the project was to obtain aerial imagery of the minke whales using drones to obtain body length measurements (sound familiar?) (Figs. 2-4). Flying drones in Antarctica over minke whales was an amazing experience. The minke whales were often found deep within the bays amongst ice floes and brash ice where they can be very tricky to spot, as they’ll often surface and then quickly disappear, hence their nickname “sneaky minkes”. They also appear “playful” and “athletic” as they are incredibly quick and maneuverable, doing barrel rolls and quick bank turns while they swim. Check out my past blog to read more on accounts of flying over these amazing whales.

In total, our team collected 437 hours of tag data consisting of day- and night-time foraging behaviors. While the proportion of time spent foraging and the number of lunges per dive (~3-4) was similar between day- and night-time foraging, daytime foraging was much deeper (~72 m) compared to nighttime foraging (~28 m) due to vertical migration of Antarctic krill, their main food source. Overall, nighttime foraging was much more intense than daytime foraging, with an average of 165 lunges per hour during the night compared to 53 lunges per hour during the day. These shallower nighttime dives enabled quicker surface sequences for replenishing oxygen reserves to then return to foraging, whereas the deeper dives during the day required longer surface recovery times before beginning another foraging dive. Thus, nighttime dives are a more efficient and critical component of minke whale foraging.

When it comes to body size, there was no relationship between dive depth and dive duration with body length, except for daytime deep dives, where longer minke whales dove for longer periods than smaller whales. These longer dive times also require longer surface times to replenish oxygen reserves. Longer minke whales can gulp larger amounts of food and thus need longer filtration times to process water from each engulfment. For example, a 9 m minke whale will take 50% longer to filter water through its baleen compared to a 5 m minke whale. In turn, smaller minke whales would need to feed more frequently than larger minke whales in order to maintain efficient foraging. This decreasing efficiency with smaller body size shines light on a broader trend for filter feeders that we refer to in our study as the minimum-size constraint (MSC) hypothesis: “while the maximum size of a filter-feeding body plan will be restricted by physical properties, the minimum size is restricted by the energetic efficiency of filter feeding and the time required to extract sufficient particles from the water” (Cade et al. 2023). When we examined the scaling of maximum feeding rates of minke whales, we found evidence of a minimum size constraint on efficiency at lengths around 5 m. Interestingly, the weaning length of minke whales is reported to be 4.5 – 5.5 m. Before weaning, newborn/yearling minke whales that are smaller than 4.5 – 5.5 m have a different foraging strategy where they are dependent on maternal milk. Thus, it is likely that the body size at weaning is influenced by the minimum size at which this specialized foraging technique of lunge feeding becomes efficient.

This study helps inform the evolutionary pathway for filter feeding whales and suggests that efficient filter feeding and gigantism likely co-evolved within the last 5 million years when ocean conditions changed to support larger prey patches suitable for lunge feeding. It is interesting to think about the MSC hypothesis for other baleen whale species that employ alternative filter feeding techniques, such as gray whales that generally use a form of filter feeding called suction feeding. Gray whales are estimated to have a birth length of ~4.6 m (Agbayani et al., 2020), and the body length of newly weaned calves that we have observed along the Oregon Coast from drone imagery seem to be ~8 – 9 m. Perhaps this is the minimum size of when suction feeding becomes efficient for a gray whale? This is something the GEMM Lab hopes to further explore as we continue to collect foraging data from suction cup tags and behavior and body size measurements from drone imagery.

References

Agbayani, S., Fortune, S. M., & Trites, A. W. (2020). Growth and development of North Pacific gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus). Journal of Mammalogy, 101(3), 742-754.

Cade, D.E., Kahane-Rapport, S.R., Gough, W.T., Bierlich, K.C., Linksy, J.M.J., Johnston, D.W., Goldbogen, J.A., Friedlaender, A.S. (2023). Ultra-high feeding rates of Antarctic minke whales imply a lower limit for body size in engulfment filtration feeders. Nature Ecology and Evolution. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-023-01993-2

Paolo S. Segre, William T. Gough, Edward A. Roualdes, David E. Cade, Max F. Czapanskiy, James Fahlbusch, Shirel R. Kahane-Rapport, William K. Oestreich, Lars Bejder, K. C. Bierlich, Julia A. Burrows, John Calambokidis, Ellen M. Chenoweth, Jacopo di Clemente, John W. Durban, Holly Fearnbach, Frank E. Fish, Ari S. Friedlaender, Peter Hegelund, David W. Johnston, Douglas P. Nowacek, Machiel G. Oudejans, Gwenith S. Penry, Jean Potvin, Malene Simon, Andrew Stanworth, Janice M. Straley, Andrew Szabo, Simone K. A. Videsen, Fleur Visser, Caroline R. Weir, David N. Wiley, Jeremy A. Goldbogen; Scaling of maneuvering performance in baleen whales: larger whales outperform expectations. J Exp Biol 1 March 2022; 225 (5): jeb243224. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.243224