By Lisa Hildebrand, MSc student, OSU Department of Fisheries & Wildlife, Marine Mammal Institute, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

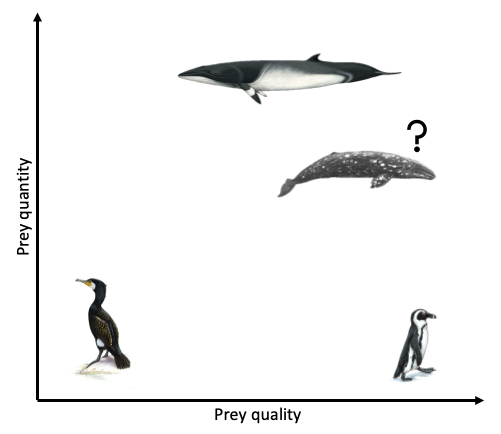

When humans count calories it is typically to regulate and limit calorie intake. What I am wondering about is whether gray whales are aware of caloric differences in the prey that is available to them and whether they make foraging decisions based on those differences. In last week’s post, Dawn discussed what makes a good meal for a hungry blue whale. She discussed that total prey biomass of a patch, as well as how densely aggregated that patch is, are the important factors when a blue whale is picking its next meal. If these factors are important for blue whales, is it same for gray whales? Why even consider the caloric value of their prey?

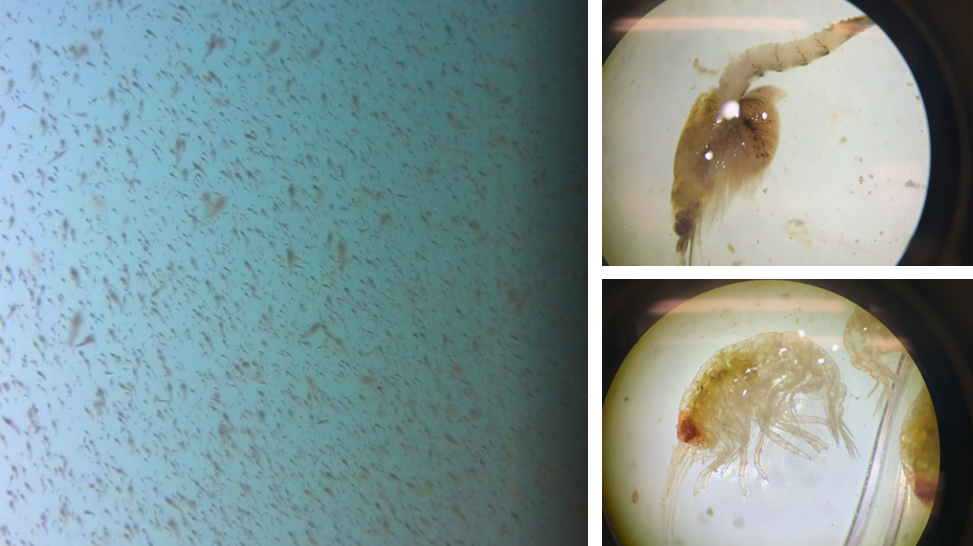

Gray and blue whales are different in many ways; one way is that blue whales are krill specialists whereas gray whales are more flexible foragers. The Pacific Coast Feeding Group (PCFG) of gray whales in particular are known to pursue a more varied menu. Previous studies along the PCFG range have documented gray whales feeding on mysid shrimp (Darling et al. 1998; Newell 2009), amphipods (Oliver et al. 1984; Darling et al. 1998), cumacean shrimp (Jenkinson 2001; Moore et al. 2007; Gosho et al. 2011), and porcelain crab larvae (Dunham and Duffus 2002), to name a few. Based on our observations in the field and from our drone footage, we have observed gray whales feeding on reefs (likely on mysid shrimp), benthically (likely on burrowing amphipods), and at the surface on crab larvae (Fig. 1). Therefore, while both blue and PCFG whales must make decisions about prey patch quality based on biomass and density of the prey, gray whales have an extra decision to make based on prey type since their prey menu items occupy different habitats that require different feeding tactics and amount of energy to acquire them. In light of these reasons, I hypothesize that prey caloric value factors into their decision of prey patch selection.

This prey selection process is crucial since PCFG gray whales only have about 6 months to consume all the food they need to migrate and reproduce (even less for the Eastern North Pacific (ENP) gray whales since their journey to their Arctic feeding grounds is much longer). You may be asking, well if feeding is so important to gray whales, then why not eat everything they come across? Surely, if they ate every prey item they swam by, then they would be fine. The reason it isn’t quite this simple is because there are energetic costs to travel to, search for, and consume food. If an individual whale simply eats what is closest (a small, poor-quality prey patch) and uses up more energy than it gains, it may be missing out on a much more beneficial and rewarding prey patch that is a little further away (that patch may disperse or another whale may eat it by the time this whale gets there). Scientists have pondered this decision-making process in predators for a long time. These ponderances are best summed up by two central theories: the optimal foraging theory (MacArthur & Pianka 1966) and the marginal value theorem (Charnov 1976). If you are a frequent reader of the blog, you have probably heard these terms once or twice before as a lot of the questions we ask in the GEMM Lab can be traced back to these concepts.

Optimal foraging theory (OFT) states that a predator should pick the most beneficial resource for the lowest cost, thereby maximizing the net energy gained. So, a gray whale should pick a prey patch where it knows that it will gain more energy from consuming the prey in the patch than it will lose energy in the process of searching for and feeding on it. Marginal value theorem elaborates on this OFT concept by adding that the predator also needs to consider the cost of giving up a prey patch to search for a new one, which may or may not end up being more profitable or which may take a very long time to find (and therefore cost more energy).

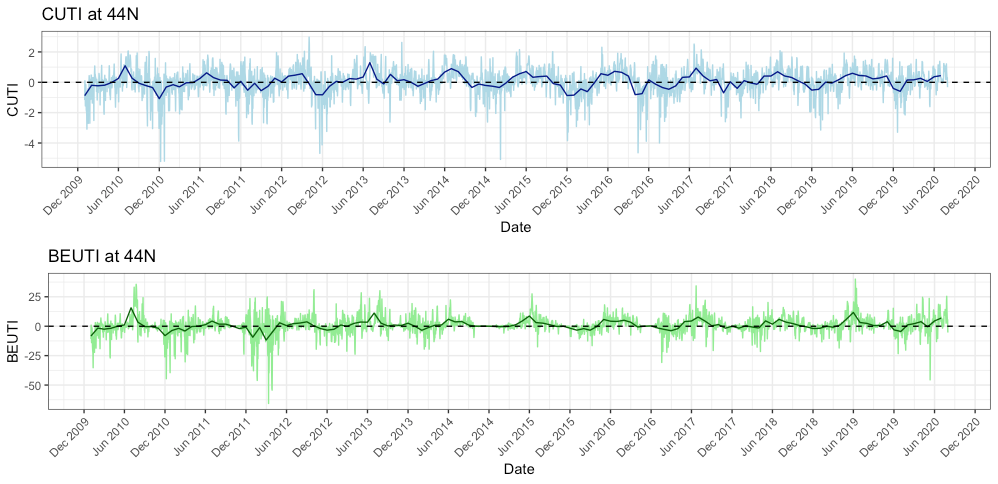

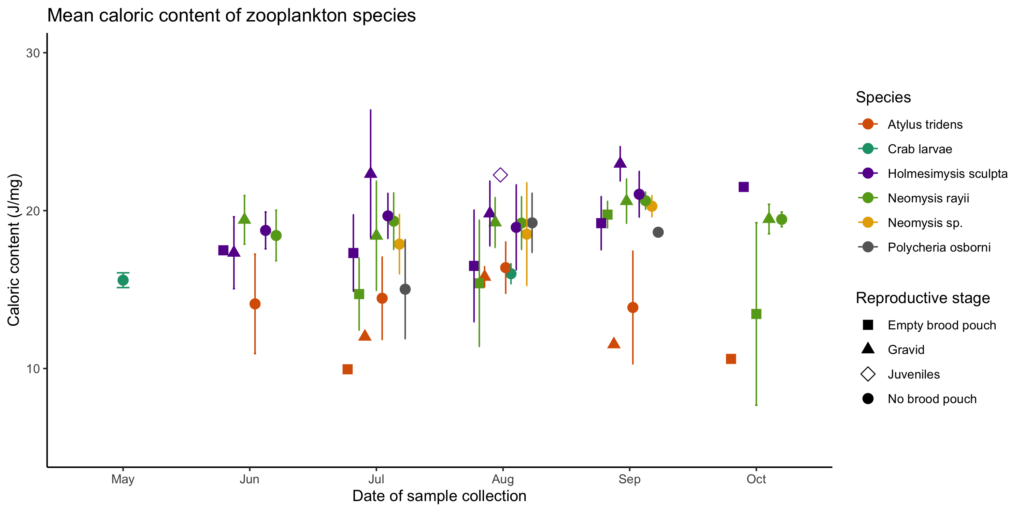

The second chapter of my thesis will investigate whether individual gray whales have foraging preferences by relating feeding location to prey quality (community composition) and quantity (relative density). However, in order to do that, I first must know about the quality of the individual prey species, which is why my first chapter explores the caloric content of common coastal zooplankton species in Oregon that may serve as gray whale prey. The lab work and analysis for that chapter are completed and I am in the process of writing it up for publication. Preliminary results (Fig. 2) show variation in caloric content between species (represented by different colors) and reproductive stages (represented by different shapes), with a potential increasing trend throughout the summer. These results suggest that some species and reproductive stages may be less profitable than others based solely on caloric content.

Now that we have established that there may be bigger benefits to feeding on some species over others, we have to consider the availability of these zooplankton species to PCFG whales. Availability can be thought of in two ways: 1) is the prey species present and at high enough densities to make searching and foraging profitable, and 2) is the prey species in a habitat or depth that is accessible to the whale at a reasonable energetic cost? Some prey species, such as crab larvae, are not available at all times of the summer. Their reproductive cycles are pulsed (Roegner et al. 2007) and therefore these prey species are less available than species, such as mysid shrimp, that have more continuous reproduction (Mauchline 1980). Mysid shrimp appear to seek refuge on reefs in rock crevices and among kelp, whereas amphipods often burrow in soft sediment. Both of these habitat types present different challenges and energetic costs to a foraging gray whale; it may take more time and energy to dislodge mysids from a reef, but the payout will be bigger in terms of caloric gain than if the whale decides to sift through soft sediment on the seafloor to feed on amphipods. This benthic feeding tactic may potentially be a less costly foraging tactic for PCFG whales, but the reward is a less profitable prey item.

My first chapter will extend our findings on the caloric content of Oregon coastal zooplankton to facilitate a comparison to the caloric values of the main ampeliscid amphipod prey of ENP gray whales feeding in the Arctic. Through this comparison I hope to assess the trade-offs of being a PCFG whale rather than an ENP whale that completes the full migration cycle to the primary summer feeding grounds in the Arctic.

References

Charnov, E. L. 1976. Optimal foraging: the marginal value theorem. Theoretical Population Biology 9:129-136.

Darling, J. D., Keogh, K. E. and T. E. Steeves. 1998. Gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) habitat utilization and prey species off Vancouver Island, B.C. Marine Mammal Science 14(4):692-720.

Dunham, J. S. and D. A. Duffus. 2002. Diet of gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) in Clayoquot Sound, British Columbia, Canada. Marine Mammal Science 18(2):419-437.

Gosho, M., Gearin, P. J., Jenkinson, R. S., Laake, J. L., Mazzuca, L., Kubiak, D., Calambokidis, J. C., Megill, W. M., Gisborne, B., Goley, D., Tombach, C., Darling, J. D. and V. Deecke. 2011. SC/M11/AWMP2 submitted to International Whaling Commission Scientific Committee.

Jenkinson, R. S. 2001. Gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) prey availability and feeding ecology in Northern California, 1999-2000. Master’s thesis, Humboldt State University.

MacArthur, R. H., and E. R. Pianka. 1966. On optimal use of a patchy environment. American Naturalist 100:603-609.

Mauchline, J. 1980. The larvae and reproduction in Blaxter, J. H. S., Russell, F. S., and M. Yonge, eds. Advances in Marine Biology vol. 18. Academic Press, London.

Moore, S. E., Wynne, K. M., Kinney, J. C., and C. M. Grebmeier. 2007. Gray whale occurrence and forage southeast of Kodiak Island, Alaska. Marine Mammal Science 23(2)419-428.

Newell, C. L. 2009. Ecological interrelationships between summer resident gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) and their prey, mysid shrimp (Holmesimysis sculpta and Neomysis rayii) along the central Oregon coast. Master’s thesis, Oregon State University.

Oliver, J. S., Slattery, P. N., Silberstein, M. A., and E. F. O’Connor. 1984. Gray whale feeding on dense ampeliscid amphipod communities near Bamfield, British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Zoology 62:41-49.

Roegner, G. C., Armstrong, D. A., and A. L. Shanks. 2007. Wind and tidal influences on larval crab recruitment to an Oregon estuary. Marine Ecology Progress Series 351:177-188.