By Dawn Barlow1 and Johanna Rayl2

1PhD Candidate, Oregon State University Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

2PhD Student, Northwestern University Department of Economics

The Greek word “oikos” refers to the household and serves as the root of the words ecology and economics. Although perhaps surprising, the common origin reflects a shared set of basic questions and some shared theoretical foundations related to the study of how lifeforms on earth use scarce resources and find equilibrium in their respective “households”. Early ecological and economic theoretical texts drew inspiration from one another in many instances. Paul Samuelson, fondly referred to as “the father of modern economics,” observed in his defining work Foundations of Economic Analysis that the moving equilibrium in a market with supply and demand is “essentially identical with the moving equilibrium of a biological or chemical system undergoing slow change.” Likewise, early theoretical ecologists recognized the strength of drawing on theories previously established in economics (Real et al. 1991). Similar broad questions are central to researchers in both fields; in a large and dynamic system (termed “macro” in economics) scale, ecologists and economists alike work to understand where competitive forces find equilibrium, and an in individual (or micro) scale, they ask how individuals make behavior choices to maximize success given constraints like time, energy, wealth, or physical resources.

The central model economists have in mind when trying to understand human choices involves “constrained optimization”: what decision will maximize a person, family, firm, or other agent’s objectives given their limitations? For example, someone that enjoys relaxing but also seeks a livable income must choose how much time to devote to working versus relaxing, given the constraint of having just 24 hours in the day, and given the wage they receive from working. An economist studying this decision may want to learn about how changes in the wage will affect that person’s choice of working hours, or how much they dislike working relative to relaxing. Along similar lines, early ecologists theorized that organisms could be selected for one of two optimization strategies: minimizing the time spent acquiring a given amount of energy (i.e., calories from food), or maximizing total energy acquisition per unit of time (Real et al. 1991). Foundational work in the field of economics clarified numerous technical details about formulating and solving such optimization problems. Returning to the example of the leisure time decision, economic theory asks: does it matter if we model this decision as maximizing income given wages and limited time, or as minimizing hours spent working given a desired lifetime income?; can we formulate a “utility function” that describes how well-off someone is with a given income and amount of leisure?; can we solve for the optimal amount of leisure with pen and paper? The toolkit arising from this work serves as a jumping off point for all contemporary economic research, and the kinds of choices understood under this framework is vast, from, where should a child attend school?; to, how should a government allocate its budget across public resources?

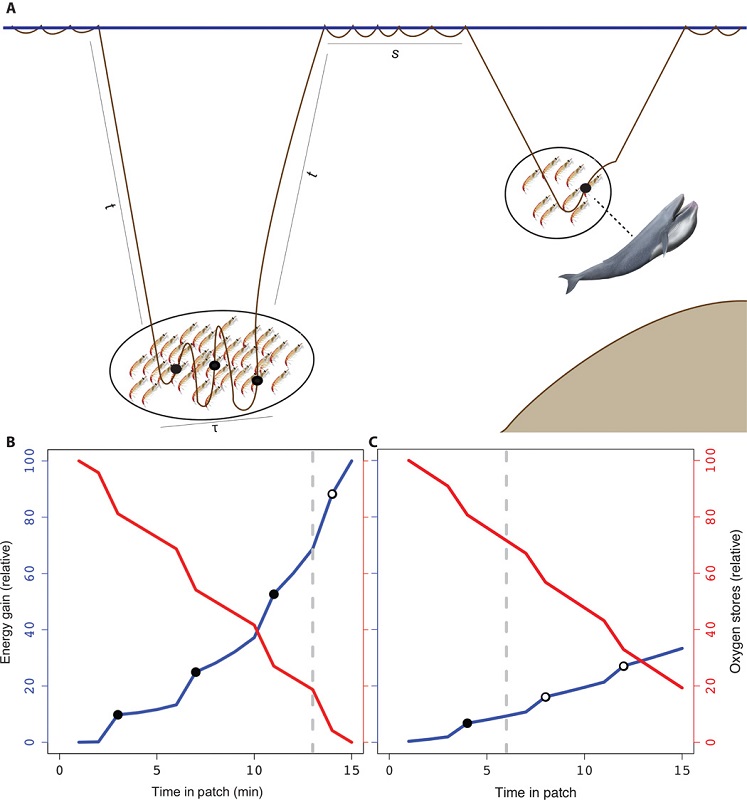

Early work in ecology drew from foundational concepts in economics, following the realization that the strategies by which organisms exploit resources most efficiently also involve optimization. This parallel was articulated by MacArthur and Pianka in their foundational 1966 paper Optimal Use of a Patchy Environment, in which they state: “In this paper we undertake to determine in which patches a species would feed and which items would form its diet if the species acted in the most economical fashion. Hopefully, natural selection will often have achieved such optimal allocation of time and energy expenditures.” Subsequently, this idea was refined into what is known in ecology as the marginal value theorem, which states that an animal should remain in a prey patch until the rate of energy gain drops below the expected energy gain in all remaining available patches (Charnov 1976). In other words, if it is more profitable to switch prey patches than to stay, an animal should move on. These optimization models therefore allow ecologists to pose specific evolutionary and behavioral hypotheses, such as examining energy acquisition over time to understand selective forces on foraging behavior.

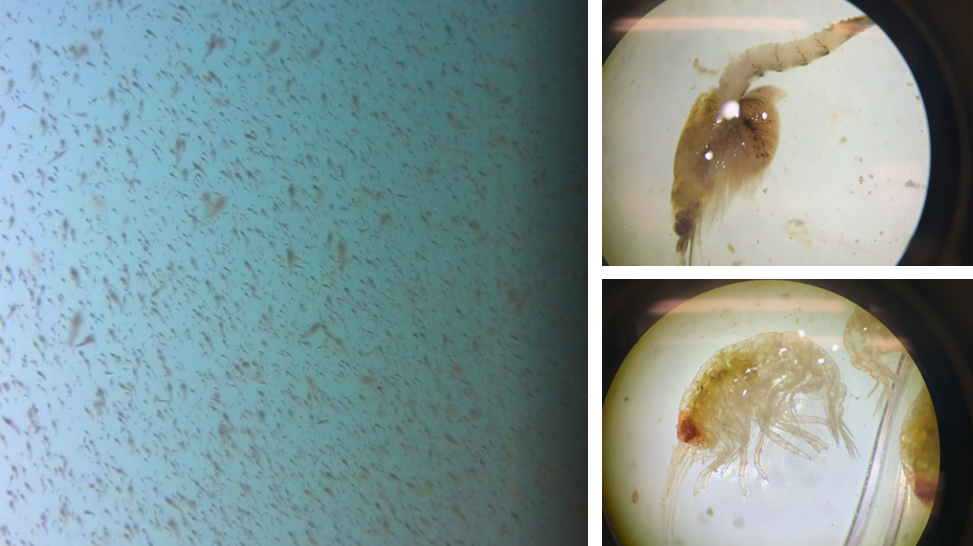

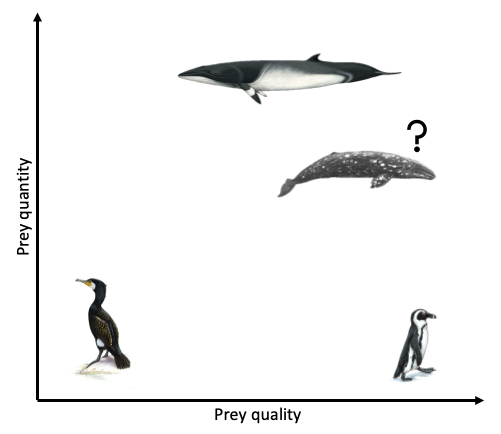

As the largest animals on the planet, blue whales have massive prey requirements to meet energy demands. However, they must balance their need to feed with costs such as oxygen consumption during breath-holding, the travel time it takes to reach prey patches at depth, the physiological constraints of diving, and the necessary recuperation time at the surface. It has been demonstrated that blue whales forage selectively to optimize this energetic budget. Therefore, blue whales should only feed on krill aggregations when the energetic gain outweighs the cost (Fig. 1), and this pattern has been empirically demonstrated for blue whale populations in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Canada (Doniol-Valcroze et al. 2011), in the California Current, (Hazen et al. 2015) and in New Zealand (Torres et al. 2020).

The notion of the marginal value theorem is likewise at work in countless economic settings. Economic theory predicts that a farmer cultivating two crops would allocate resources into each crop such that the returns to adding more resources into each crop are the same. If not, she should move resources from the less productive crop to the one where marginal gains are larger. A fisherman, according to this notion, continues to fish longer into the season until the marginal value of one additional day at sea equals the marginal cost of their time, effort, and expenses. These predictions are intuitive by the same logic as the blue whale choosing where to forage, and derive from the mathematics of constrained and unconstrained optimization. Reassuringly, empirical work finds evidence of such profit-maximizing behavior in many settings. In a recent working paper, Burlig, Preonas, and Woerman explore how farmers’ water use in California responds to changes in the price of electricity, which effectively makes groundwater irrigation more expensive due to electric pumping. They find that farmers are very responsive to these changes in marginal cost. Farmers achieve this reduction in water use predominantly by switching to less water-intensive crops and fallowing their land (Burlig, Preonas, and Woerman 2020).

Undoubtedly there are fundamental differences between an ecosystem with interacting biotic and abiotic components and the human-economic environment with its many social and political structures. But for certain types of questions, the parallels across the shared optimization problems are striking. The foundational theories discussed here have paved the way for subsequent advances in both disciplines. For example, the field of behavioral ecology explores how competition and cooperation between and within species affects fitness of populations. Reflecting on early seminal work lends some perspective on how an area of research has evolved. Likewise, exploring parallels between disciplines sheds light on common threads, in turn revealing insights into each discipline individually.

References:

Burlig, Fiona, Louis Preonas, and Matt Woerman (2020). Groundwater, energy, and crop choice. Working Paper.

Charnov EL (1976) Optimal foraging: The marginal value theorem. Theoretical Population Biology 9:129–136.

Doniol-Valcroze T, Lesage V, Giard J, Michaud R (2011) Optimal foraging theory predicts diving and feeding strategies of the largest marine predator. Behavioral Ecology 22:880–888.

Hazen EL, Friedlaender AS, Goldbogen JA (2015) Blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) optimize foraging efficiency by balancing oxygen use and energy gain as a function of prey density. Science Advces 1:e1500469–e1500469.

MacArthur RH, Pianka ER (1966) On optimal use of a patchy environment. The American Naturalist 100:603–609.

Real LA, Levin SA, Brown JH (1991) Part 2: Theoretical advances: the role of theory in the rise of modern ecology. In: Foundations of ecology: classic papers with commentaries.

Samuelson, Paul (1947). Foundations of Economic Analysis. Harvard University Press.

Torres LG, Barlow DR, Chandler TE, Burnett JD (2020) Insight into the kinematics of blue whale surface foraging through drone observations and prey data. PeerJ 8:e8906.