By Dawn Barlow, PhD Candidate, OSU Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

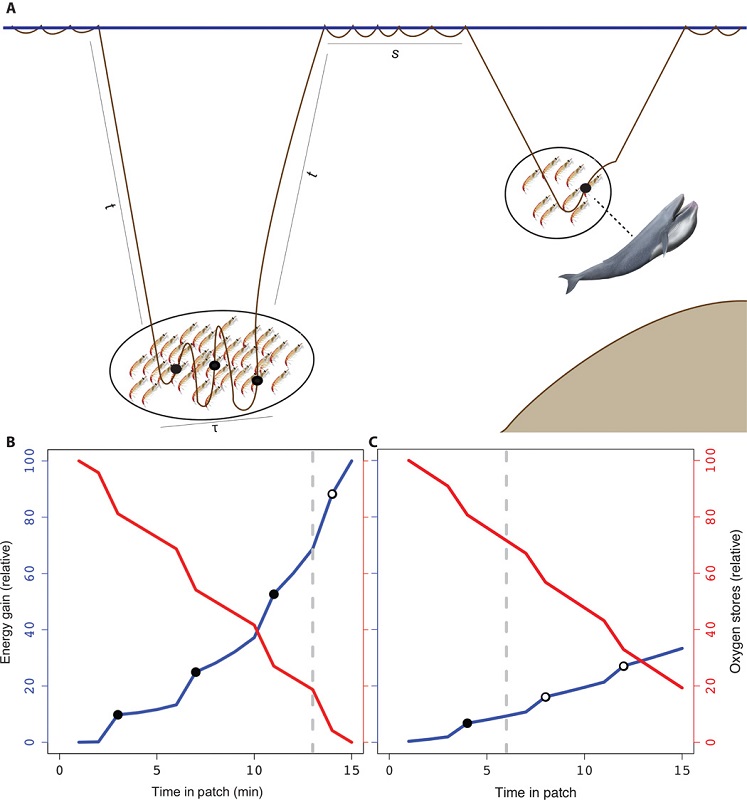

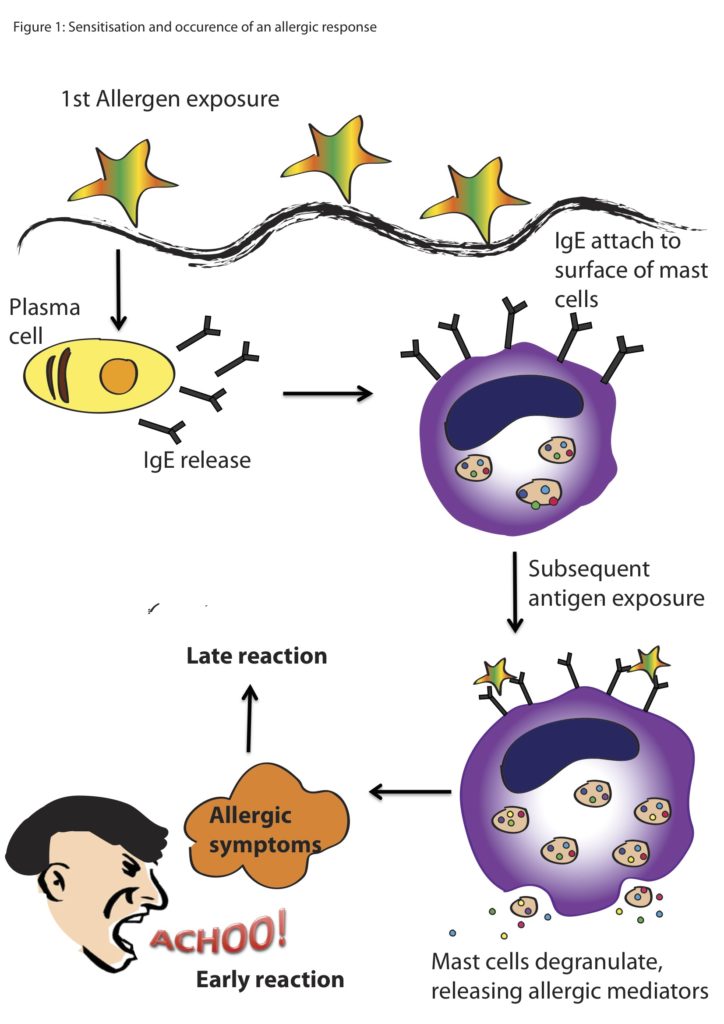

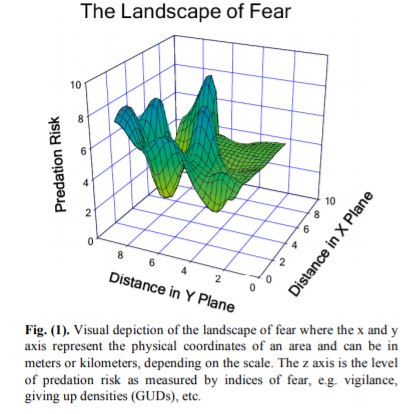

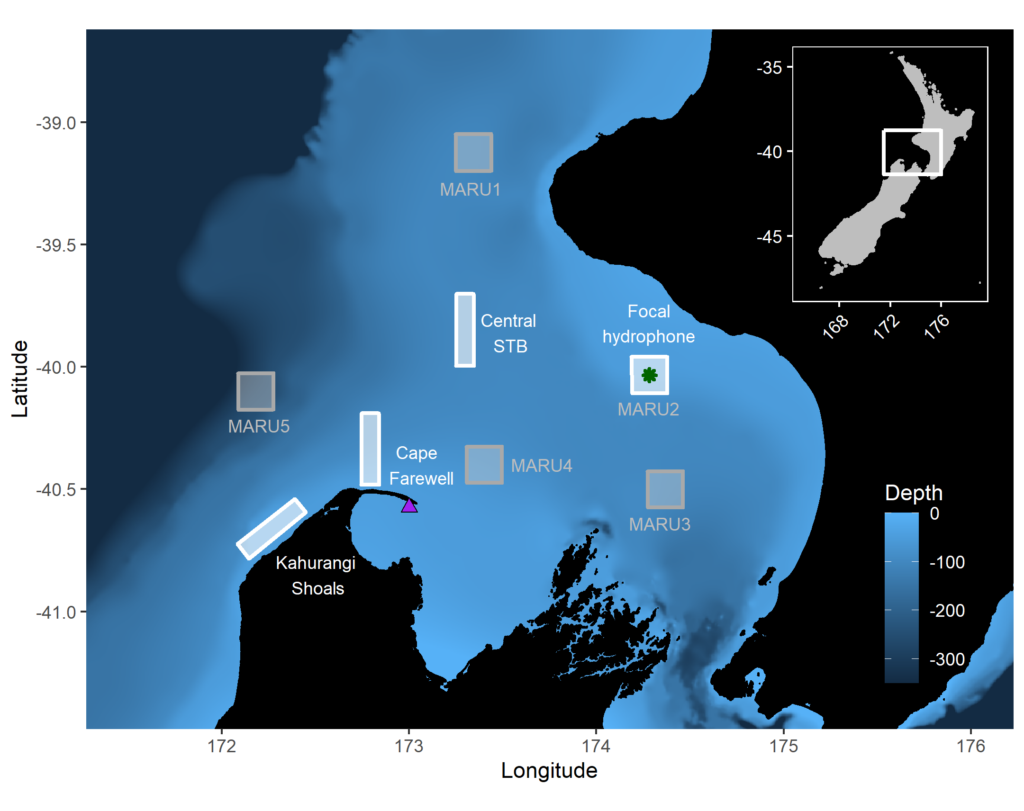

To understand the complex dynamics of an ecosystem, we need to examine how physical forcing drives biological response, and how organisms interact with their environment and one another. The largest animal on the planet relies on the wind. Throughout the world, blue whales feed areas where winds bring cold water to the surface and spur productivity—a process known as upwelling. In New Zealand’s South Taranaki Bight region (STB), westerly winds instigate a plume of cold, nutrient-rich waters that support aggregations of krill, and ultimately lead to foraging opportunities for blue whales. This pathway, beginning with wind input and culminating in blue whale occurrence, does not take place instantaneously, however. Along each link in this chain of events, there is some lag time.

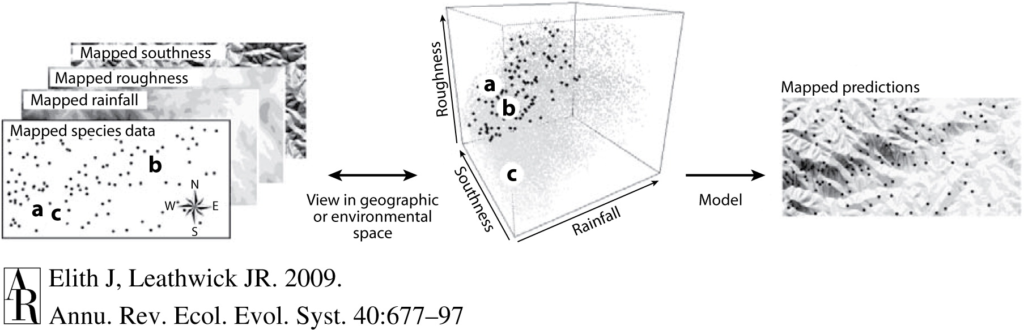

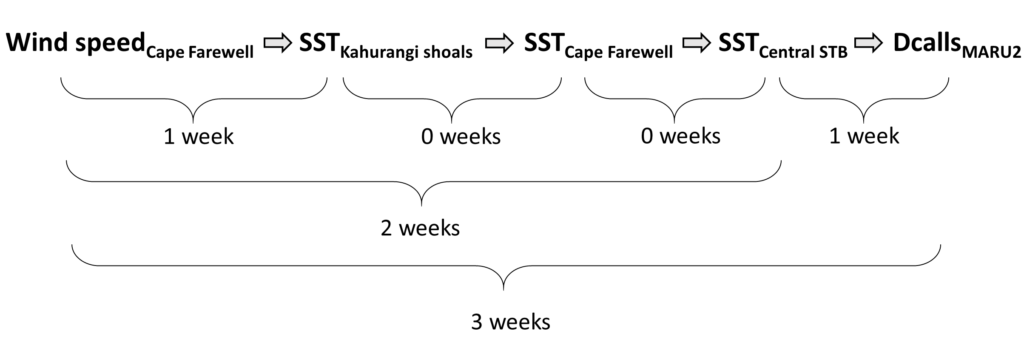

Our recent paper published in Scientific Reports examines the lags between wind, upwelling, and blue whale occurrence patterns. While marine ecologists have long acknowledged that lag plays a role in what drives species distribution patterns, lags are rarely measured, tested, and incorporated into studies of marine predators such as whales. Understanding lags has the potential to greatly improve our ability to predict when and where animals will be under variable environmental conditions. In our study, we used timeseries analysis to quantify lag between different metrics (wind speed, sea surface temperature, blue whale vocalizations) at different locations. While our methods are developed and implemented for the STB ecosystem, they are transferable to other upwelling systems to inform, assess, and improve predictions of marine predator distributions by incorporating lag into our understanding of dynamic marine ecosystems.

So, what did we find? It all starts with the wind. Wind instigates upwelling over an area off the northwest coast of the South Island of New Zealand called Kahurangi Shoals. This wind forcing spurs upwelling, leading to the formation of a cold water plume that propagates into the STB region, between the North and South Islands, with a lag of 1-2 weeks. Finally, we measured the density of blue whale vocalizations—sounds known as D calls, which are produced in a social context, and associated with foraging behavior—recorded at a hydrophone downstream along the upwelling plume’s path. D call density increased 3 weeks after increased wind speeds near the upwelling source. Furthermore, we looked at the lag time between wind events and aggregations in blue whale sightings. Blue whale aggregations followed wind events with a mean lag of 2.09 ± 0.43 weeks, which fits within our findings from the timeseries analysis. However, lag time between wind and whales is variable. Sometimes it takes many weeks following a wind event for an aggregation to form, other times mere days. The variability in lag can be explained by the amount of prior wind input in the system. If it has recently been windy, the water column is more likely to already be well-mixed and productive, and so whale aggregations will follow wind events with a shorter lag time than if there has been a long period without wind and the water column is stratified.

This publication forms the second chapter of my PhD dissertation. However, in reality it is the culmination of a team effort. Just as whale aggregations lag wind events, publications lag years of hard work. The GEMM Lab has been studying New Zealand blue whales since Leigh first hypothesized that the STB was an undocumented foraging ground in 2013. I was fortunate enough to join the research effort in 2016, first as a Masters student and now as a PhD Candidate. I remember standing on the flying bridge of R/V Star Keys in New Zealand in 2017, when early in our field season we saw very few blue whales. Leigh and I were discussing this, with some frustration. Exclamations of “This is cold, upwelled water! Where are the whales?!” were followed by musings of “There must be a lag… It has to take some time for the whales to respond.” In summer 2019, Christina Garvey came to the GEMM Lab as an intern through the NSF Research Experience for Undergraduates program. She did an outstanding job of wrangling remote sensing and blue whale sighting data, and together we took on learning and understanding timeseries analysis to quantify lag. In a meeting with my PhD committee last spring where I presented preliminary results, Holger Klinck chimed in with “These results are interesting, but why haven’t you incorporated the acoustic data? That is a whale timeseries right there and would really add to your analysis”. Dimitri Ponirakis expertly computed the detection area of our hydrophone so we could adequately estimate the density of blue whale calls. Piecing everything together, and with advice and feedback from my PhD committee and many others, we now have a compelling and quantitative understanding of the upwelling dynamics in the STB ecosystem, and have thoroughly described the pathway from wind to whales in the region.

Our findings are exciting, and perhaps even more exciting are the implications. Understanding the typical patterns that follow a wind event and how the upwelling plume propagates enables us to anticipate what will happen one, two, or up to three weeks in the future based on current conditions. These spatial and temporal lags between wind, upwelling, productivity, and blue whale foraging opportunities can be harnessed to generate informed forecasts of blue whale distribution in the region. I am thrilled to see this work in print, and equally thrilled to build on these findings to predict blue whale occurrence patterns.

Reference: Barlow, D.R., Klinck, H., Ponirakis, D., Garvey, C., Torres, L.G. Temporal and spatial lags between wind, coastal upwelling, and blue whale occurrence. Sci Rep 11, 6915 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86403-y