By: Erin Pickett, M.S. Student, Oregon State University

GEMM lab UPDATE: Amanda Holdman successfully defended her master’s thesis this week!

Amanda wisely planned her defense date for November 7th, 2016, the day before Election Day. As I anxiously watched the New York Times election forecast needle bounce back and forth, from left to right on Election night, I thought to myself, why didn’t I think of that? If you are unfamiliar with what I am talking about, this “forecast needle” was an animated graphic on the NYT website that bounced constantly all night between the two Presidential candidates. It caused a great deal of unease for those of us that found it difficult to look away. The animation sparked some debate online among bloggers and tweeters, my favorite comment being, “it borders on irresponsible data visualization”. I came to the realization pretty quickly on Tuesday night that despite the outcome of the election, I would still need to turn in my thesis the following week.

Personally, I did not feel motivated to get out of bed on Wednesday. I wasn’t feeling inspired, or overcome with positive thoughts about what my day of thesis writing would bring. Thankfully, here at OSU, we graduate students have good leaders to keep us on track. Wednesday afternoon, we received an encouraging email from our Department Head, Dr. Selina Heppell. I took away two important points from this email. The first: stay positive, and remember that we do great work with great people and that our work matters. Secondly, think about the lessons that we have learned from this election. For those of us that were shocked about who our country has chosen as the next President of the United States, one important lesson is that we need to focus more on engaging people who exist outside of the echo chambers of our scientific communities.

The recent election has left many scientists and environmentalists concerned about what the future political climate will bring in terms of research funding, job opportunities, and environmental protection. More so now than ever it is important to remain positive and hopeful, and to reconsider the way we communicate our research and engage outside communities whose views are unlike our own. Both of these tasks are particularly challenging due to the long list of environmental problems we face. As it turns out, having a hopeful outlook is important for tackling seemingly insurmountable conservation issues, and empowering others to want to do the same (Swaisgood & Sheppard 2010, Garnett & Lindenmayer 2011).

The title of this blog comes from an eloquent commencement speech by Paul Hawken about the importance of remaining optimistic when the data tells us otherwise. While the address was given to the University of Portland class of 2009, I think it is worth reading because it is a relevant and moving reminder of why hope is important.

But, before you read that, take a look at what has been done recently to protect biodiversity around the world-

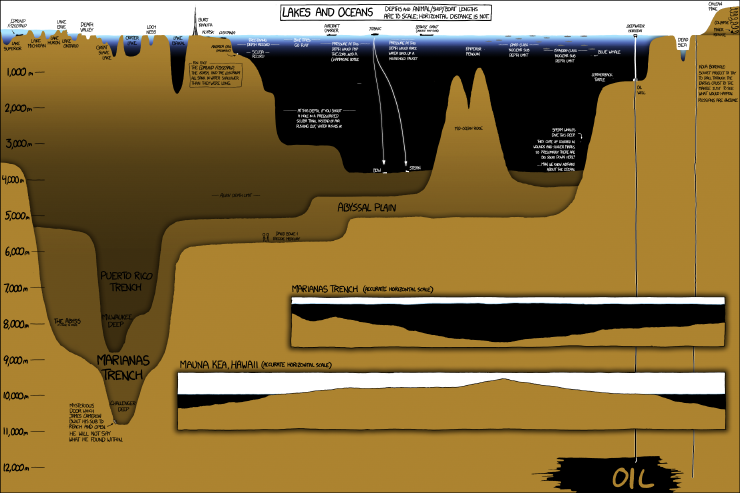

President Obama quadrupled the size of a marine national monument in Hawaii. You can read more about the significance of this monument, called Papahānaumokuākea, in a previous blog of mine.

Soon after announcing the expansion of Papahānaumokuākea, President Obama established the first marine national monument in the Atlantic. You can read more about the aptly named Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument here.

And finally, to top it off, an international body comprised of 24 countries, called the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, recently came to a consensus to designate a vast portion of the Antarctic’s remote Ross Sea as the world’s largest marine reserve.

References

- Garnett, S. T., & Lindenmayer, D. B. (2011). Conservation science must engender hope to succeed. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 26(2), 59-60.

- Swaisgood, R. R., & Sheppard, J. K. (2010). The culture of conservation biologists: Show me the hope!. BioScience, 60(8), 626-630.