The GEMM Lab

Alexa Kownacki first contacted me in October 2016 to enquire about being my PhD student and joining the GEMM Lab. She spoke with passion, intellect, curiosity and honesty, to which I was immediately drawn. Over the next four years, we were privileged to have her brilliance, kindness, wit and effervescence in our world. I am devastated to communicate here – on the GEMM Lab blog that Alexa frequently contributed to with enthusiasm and talent – that Alexa Kownacki passed away on Tuesday, November 17, 2020. The GEMM Lab has been shocked and deeply saddened by losing Alexa from our lives. She embodied joy, and recognized and relished beauty everywhere, and in each of us. Her ability to give support, love, and understanding was limitless, as was her passion for marine conservation and education. Our sorrow is profound, but we want to remember Alexa’s life with the brightness, color and laughter it deserves, for that’s how she lived. Below are memories of Alexa from each of us in the GEMM Lab who knew and loved Alexa, followed by a video montage of Alexa in life. Please visit this memorial website to contribute your stories of Alexa, as well as read other tributes and post photos.

Leigh

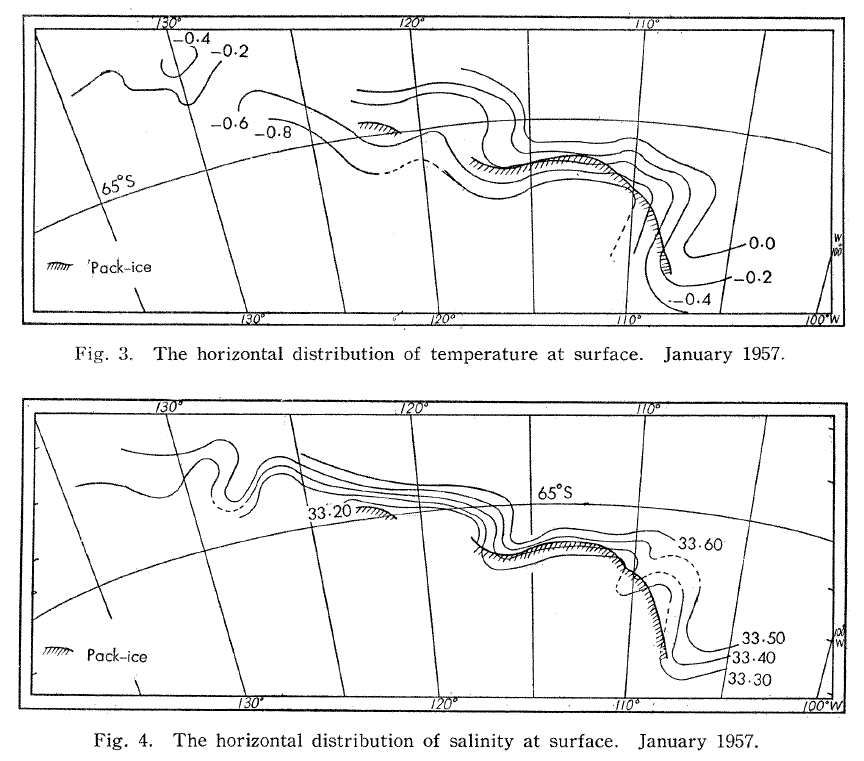

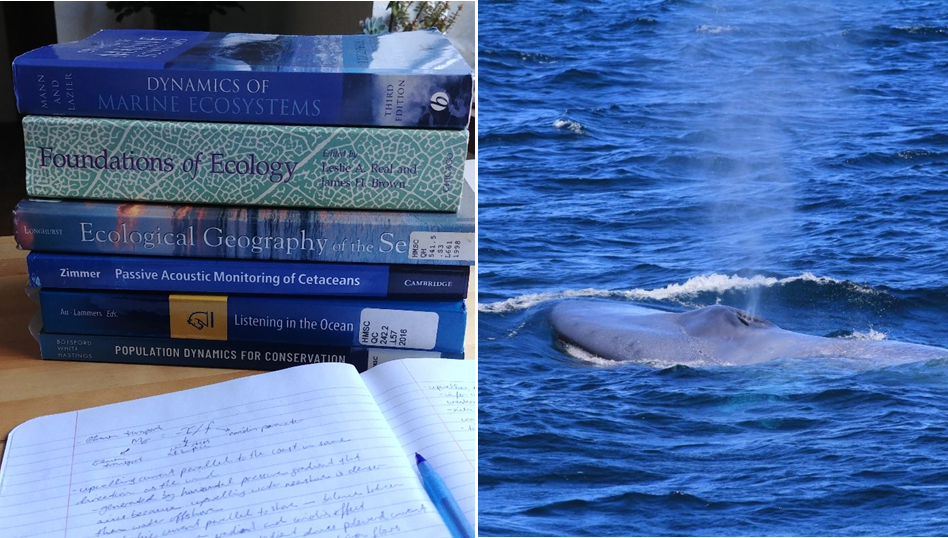

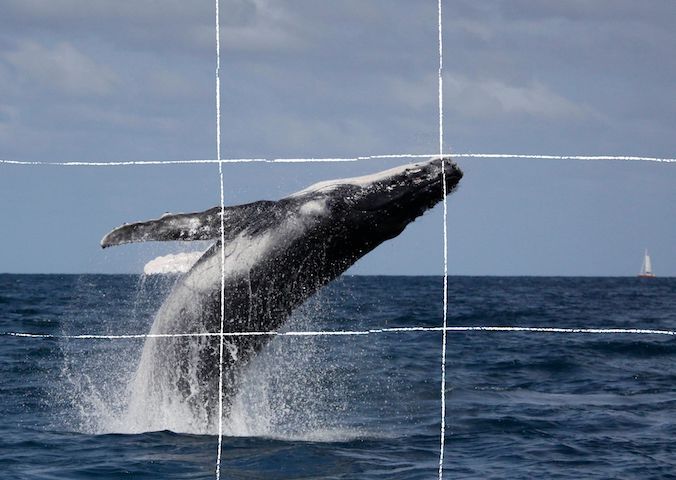

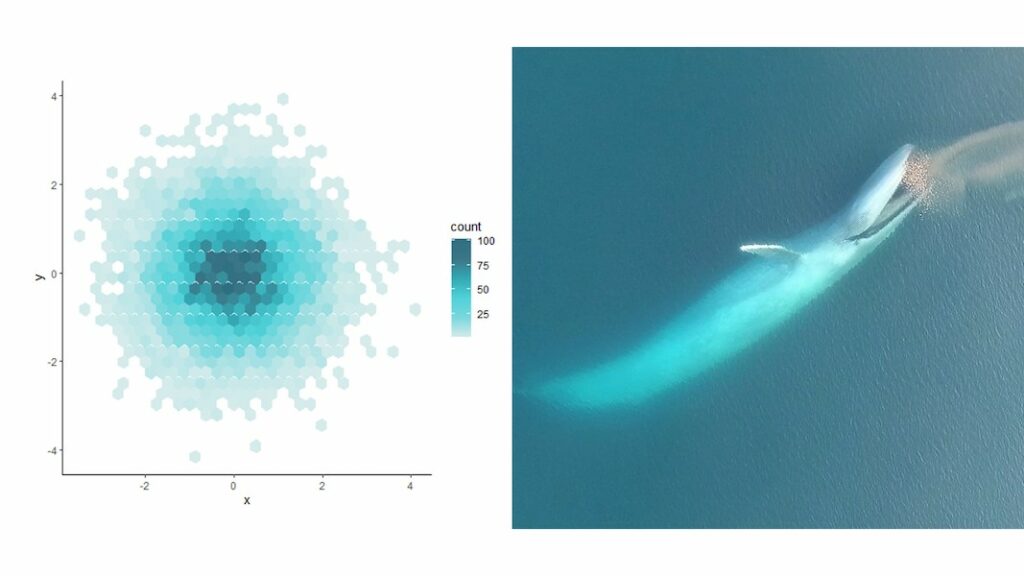

Alexa loved the ocean and seemed more at-home while at-sea than almost anyone I know. I asked Alexa to join me aboard the RV Oceanus for a STEM research cruise in September 2018 where we took high school students and teachers to sea to teach them how we collect marine mammal and oceanographic data. (Alexa wrote a lovely blog about this cruise.) I was not surprised by her enthusiasm – that was her nature – but I was utterly amazed at how easily Alexa mentored the students, communicated with the crew, balanced teaching with humor and humility, created learning moments everywhere, and supported everyone on-board so they felt welcomed and comfortable. During this cruise, Alexa was my partner, my teammate. We were both in our element and shared so much joy with the privilege to be at-sea, laughter at the excitement and adventure, inspiration at watching the next generation of marine scientists learn, and awe for the beauty that the ocean holds. This is how I will remember you, Alexa. Your free, beautiful, kind, joyous spirit will always be with me.

Dom

For anyone who knew Alexa, you knew she had an uncanny ability to connect with others on such a personal level that made you feel truly valued and loved. No matter the circumstances, she made it a point to always show up for those she cared about, which makes it extremely difficult to choose just one memory to remember her by. Instead, I’m choosing to remember her by the way she made me feel, as a human and a friend. Even during the most challenging of times, Alexa always wanted to know how I was doing and what I was doing outside of school to take care of myself. I can’t count the number of times she pulled me away from my work to go out dancing at the Peacock or drag shows, hiking on our weekends, or even making short donut runs to Benny’s Donuts. She understood that even scientists have basic needs for personal connection, fun and enjoyment, and love. If there’s anything Alexa’s passing has taught me, it is this: always show up for your fellow scientists and colleagues as people and friends first, because our support for one another will no doubt leave a longer-standing and greater impact on this world than our achievements and discoveries. Her passing will be my constant reminder that we all deserve to be treated and valued with love and dignity. Alexa, thank you for teaching me this valuable lesson, and I hope I get the chance to impact someone else’s life, as much as you have mine. I love you, and I promise I’ll visit San Diego soon.

Lisa

Alexa, there are so many memories, experiences, and moments we had together that I will never forget, least of all the very first day I met you (fasten your seatbelts everyone, this story is a wildly unbelievable, yet very true, roller coaster ride). Summers were always extremely busy for you in San Diego. Yet, despite that, you didn’t hesitate when Leigh asked you to come up to Oregon in July 2018 to teach me, the newest GEMM Lab member, all there was to know about the Port Orford gray whale project. You had never met me before and you had only participated in the Port Orford project for a week the previous summer, but none of that stopped you. You flew to Portland from San Diego and made your way to Newport. We loaded up the MMI truck with all the gear and headed south towards Port Orford. So far, so good. Great, even! You pulled off the highway any chance we got so I could marvel at the beauty of the Oregon coast. But that all changed when we got to Coos Bay where we planned to stock up on groceries. You, ever so organized & thoughtful, had already compiled a grocery list but as we were going up and down the aisle, adding things to our cart, you suddenly realized that your phone was missing. We retraced our steps. Nothing. As always, you were quick on your feet, and connected to the Safeway wifi on your tablet to use the ‘Find My iPhone’ app to help solve the mystery. Lo-and-behold, your phone was no longer in the store…We drove to the location and arrived at what we always describe as a “creepy-looking motel” (although under any other circumstance the motel would have probably looked totally normal). We surveyed our surroundings and made notes (I still have that note on my phone) about all the people and vehicles we saw. One person in particular drew our attention because out of the back of his car he pulled out several…Safeway grocery bags!!! Feeling giddy about our amateur-sleuthing but also nervous because we were sitting in a pretty conspicuous white government truck in a motel parking lot, you decided that it was probably time to call the police. Two officers arrived and it soon was revealed that the man we had seen with Safeway bags had indeed just been at Safeway with his daughter. Apparently, his daughter had a habit of stealing and he told the officers he was confident that his daughter had stolen the phone and that he would call them as soon as he found it. There wasn’t much for us to do so you decided it would be best to drive to Port Orford, get settled in and once we heard from the police, we could drive back to Coos Bay. We did eventually hear from the police and drove all the way back to Coos Bay in the dark, only to find that your phone was completely destroyed. The night involved more adventures (including sleeping on the floor but that’s a whole other story), yet, the next day (the 4th of July), you let none of these events stop us from making s’mores (my first ones ever!) and watching the dinghy race & fireworks from the field station. You blazed on, with your unparalleled optimism and determination, to ensure that I not only learned everything that I needed to know to be able to run the project, but that we also had a great time while learning. Alexa, I will cherish the time we had together forever and I miss you so incredibly much.

Dawn

The day Alexa moved to Oregon to start graduate school, she learned that we were sailing here in Newport as part of Yaquina Bay Yacht Club’s Wednesday night race series. She had yet to move into her apartment, but she hopped on a sailboat that very evening. Alexa was in her element, with wind in her hair and salt spray on her face. She smiled through it all as her signature laughter rang out across the bay, and by the end of the evening she had easily become friends with the entire community. This was Alexa’s way of life. She leapt at opportunities, she poured her whole self into everything she did, and she connected with everyone immediately, deeply, and genuinely. Her optimism was unending. After long, stormy weather days at sea she would enthusiastically send a sunset photo with the caption “Red sky at night, sailors delight!” She lived every moment to the fullest, and she helped all of us see beauty, humor, and joy through her eyes. “Let’s document this, I’m taking a picture!” she’d say. Oftentimes, I’d roll my eyes. “Hey, Dawn you’re not in the picture. Lean in!” she’d insist. Now I have so many photos and memories to cherish. What a constant joy it was, dear Alexa, to be your labmate and your friend. What a heartbreaking reminder your sudden departure is to take nothing for granted, to live life to the absolute fullest, to dance often and sing loudly, and to hold nothing back. Fair winds and following seas, you beautiful, bright spirit. We love and miss you dearly. Thank you for sharing your time on earth with all of us.

Leila

Alexa was a light in my life since I met her in Oregon. I first met Alexa while living in the dorms in Newport and got to be her roommate for that summer. She would always wake up in the morning and head to the basketball court with her laptop to do some exercises, always so energetic and enthusiastic! I also shared rooms with her on multiple other occasions, including my house when she needed a place and at all of the conferences we went to together. While I was pretty much dead after an entire day of talks and was ready to go to bed, she was getting ready to go dancing. She was always SO full of energy and life. Alexa indeed knew how to enjoy life, and did it graciously.

She easily became one of my greatest friends in Oregon. She was my confidant during the struggles of grad life and was always supportive no matter what happened. Last year we were in Barcelona for a conference and my passport got lost in the mail system. She saw how nervous I was and made sure to accompany me to the other side of the city to go check if my passport had arrived, even if she already had plans for that night. Also, when I was about to defend my Ph.D. she would go do groceries for me to make sure I had enough ice cream while struggling with my presentation practice. Alexa had problems, many problems, but still went above and beyond to make sure all of her friends were taken care of.

We both loved dancing and were taking dance classes in grad school. We tried to find a dance style that we both liked so we could go to dance together, but I was already taking hip hop classes and loved it. Alexa would not accept going to hip hop as she thought it was not an inclusive and diverse space and she wanted to spend her time meeting and cherishing diverse people. She was always so thoughtful and probably one of the most inclusive people I have ever met.

Alexa’s contagious laugh, caring and optimism left me a deep mark that I am going to carry close to my heart throughout my life. She is such a great inspiration for how we should live our lives. I love you Alexa and miss you dearly. Thank you for everything. Rest in peace and keep shining wherever you are. I am sure this is just a “see you later”.

Alejandro

I had the joy to meet Alexa when I first visited the GEMM Lab in 2018, I will always remember her for her vibrant smile, her friendly kind, and for making me feel so welcomed when I arrived in Newport, she instantly made me feel among friends. I meet her so briefly because she was heading to San Diego for the summer to work on her research, she let me borrow her desk for me to work on while she was away and she left me a note written in Spanish, my native language, which meant a lot to me, and speaks about the kind of person she was, someone who would make you feel welcomed and would try finding things in common to engage and connect. We kept connected ever since, exchanging emails about work, whales, dolphins, or just to know about how we were doing, hoping to reunite again but, unfortunately, last summer due to COVID we could not meet again. The news about her leaving us just left me shocked, although I met her briefly she really impacted me, I want to be a bit like her, and be able to share the things I love in the way she did, with passion and vibrant enthusiasm. She will be missed.

Rachael

Alexa and I haven’t been in the same place at the same time for a while. On the top of my list for next time we crossed paths was to catch-up with her about her trip through the Northwest Passage and quiz her about the seabirds, the islands, and the polar bears. In September 2018, I agreed to join the R/V Oceanus on a STEM outreach cruise as a seabird observer. It was my first time as a seabird observer as I typically do better on land. I spent most of the first day in my bunk (I have queasy memories of making it up to the flying bridge, seeing the ocean, and quickly retreating). Luckily the cruise was long enough for me to gain my sea legs. I didn’t take any photos, but Alexa did and I can look back on those days through her eyes and remember the wonderful calm beautiful evening we spent on the back deck, her excitement and skill when we encountered whales, and her kind laughter when we spotted an albatross through the portal (and I wasn’t quite ready to go up to the flying bridge). I admired her outgoing confidence and enthusiasm and I will miss her presence in the GEMM lab family. In our field, people have the habit of coming round full circle and I also miss the future: reuniting with Alexa 10 years from now on a research cruise somewhere. Alexa – thank you for those moments we shared, your vision of life, and your efforts to make the ‘world a better place for all living creatures’.

Karen

Alexa threw kindness around like it was confetti and life was one big dance party. She freely gave of her time and energy and sought to raise those near her to her own level of excellence. Through her own example, she constantly reminded me, and many others, that being a kind, welcoming, and goodhearted person was just as important as academic or scientific success. Alexa always made me feel welcome in the GEMM lab (even though I’m adopted) for which I will always be grateful. What I admire most about Alexa is her strength and perseverance, and stubborn refusal to let anything life threw at her knock her off the course she chose for herself. Knowing Alexa was truly a gift. After receiving such a gift in my life, more than anything I want to say thank you to her. And so, to Alexa:Thank you for the beach breaks and the lunch dates and the ‘oh look, the sun’s out we gotta run out’ breaks. Thank you for the light and laughter you brought with you everywhere. Thank you for continually reminding me to find the joy in hard times and sitting with me in difficult moments until I could. Thank you for being goofy enough to stomp on seaweed or play on the swings with me. Thank you for keeping me entertained with silly jokes in Zoom meetings gone on too long. Thank you for being a cheerleader when I needed it, and for being so willing to share your positivity in the many pep talks you gave me. And most of all, thank you for the epic dance parties. I know you’re dancing wherever you are.

One example of Alexa’s endless determination – continuing to insist on taking selfies to document her friendships even in the age of social distancing.

Clara

I first met Alexa in Barcelona when I arrived at the apartment the GEMM lab was sharing for the conference. My first memory is that she greeted me like an old friend and made me feel instantaneously welcome. There was no awkward initial phase, we met and were friends. I adored every time we got a chance to catch up and chat. This past spring I had regular “zoom GIS dates” with Alexa to help her with GIS, but I have to admit these were 50% catch up time, and I’ve never been happier to be unproductive. She was never bothered by GIS crashing for the tenth time, something that would have most people banging their head on a desk, instead she would just say “ah well, ok so back to [whatever we were talking about]”. We bonded over field work and travel stories (she had the best travel stories). Whenever we spoke she was always supportive and kind, she truly believed in you and made sure you knew it.

Alexa, your welcoming, enthusiastic, and encouraging spirit has been an inspiration that I will carry with me always. Thank you for everything, your warm, vibrant, and brilliant presence is deeply missed.

Alexa offered to take care of some of the library plants when it was preparing to close in March. We had to buckle the plants into the backseat of my car to transport them back to Corvallis, we both found this highly amusing and naturally, Alexa wanted to document it, I am so glad she did.

Florence

Alexa was one of those rare people who is genuinely, unapologetically excited about the universe and everything in it. Like others have mentioned, if you weren’t her friend, it was only because you hadn’t met her yet. When you met her, she would quickly dig past traditional I-have-just-met-you small talk until she found a common passion or something to connect about. Our self evident enthusiasm for marine mammals and baking provided ample opportunities for geeking out together, but the ‘oh-wow-small-world’ moment that still makes me laugh is when we realised that her great uncle is the priest who celebrated my wedding!

I will remember the dedication she had to maintaining the bonds of our GEMM Lab family, regularly driving across the coastal mountains for potlucks and boardgame nights (a 2 hr round trip most folks were reluctant to make!). I will remember her laughter whether she won or lost those games, and the way she insisted we make time to set aside our work and just exist as friends. I will remember her delight when I asked her to participate in a group weaving project, and the joy in her smile at learning a new skill. Alexa is inextricably woven into the tapestry of so many lives. The fabric of the community she helped build will hold her memory, and keep us warm with the blessing of her laughter.

–Like a Sailboat–

I am standing at the edge of the shore

A ship sails in the morning breeze

And heads for the open ocean

She is beauty, She is life.

I watch her ’til she disappears over the horizon.

Someone near me says << She is Gone >>

Gone where? Gone from my sight, that’s all.

Her mast is still as tall,

Her hull still holds the strength to carry

Her cargo of humanity

Her diminishment and loss from sight is in me, not in her.

And in the moment when someone near me say:

<< She is Gone >>

There are others who, seeing a sail on the horizon,

coming towards them,

exclaim with joy: << There She Is >>

This is death.

There are no dead,

Only people on both shores.

-Author unknown

To view a video montage put together by the GEMM lab click here.

Thank you for everything Alexa, we love and miss you, may your memory be a blessing.