By Lisa Hildebrand, PhD student, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, & Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

If you are an avid reader of our blog, you probably know quite a bit about gray whales, specifically the Pacific Coast Feeding Group (PCFG) of gray whales. Of the just over 50 GEMM Lab blogs written in 2021, 43% of them were about PCFG gray whales (or at least mentioned gray whales in some way). I guess this statistic is not too surprising when you consider that six of the 10 GEMM Lab members conduct gray whale-related research. You might think that we would have reached our annual limit of online gray whale content with that many blogs featuring these gentle giants, but you would in fact be wrong…

At the end of 2021, we launched a brand new website all about gray whales called IndividuWhale! It features stories of some of the Oregon coast’s most iconic gray whales, as well as information about how we study them, stressors they experience in our waters, and even a game to test your gray whale identification skills. IndividuWhale is a true labor of love that took over a year to create and that we are extremely proud to share with you today. Before I tell you more about the website, I want to take a moment to give a huge shout out to Erik Urdahl who was instrumental in getting this website off the ground and making it as interactive and beautiful as it is – hurrah Erik!

Like us humans, gray whales have individual personalities and stories. They experience life-altering events, go through periods of stress, must provide for their offspring, and can behave differently to one another. Since Leigh & co. have been conducting in-depth research about PCFG gray whales in Oregon waters since 2016, we have been able to document several fascinating stories and events that these individuals have experienced. Take Equal, for example, a male whale that is at least 7 years old. The GEMM Lab observed Equal on consecutive days in June 2018, where on the first day he looked healthy and normal, but on the second day had fresh boat propeller-like scars on his back. Not only did we document these scars in photographs, but we were also able to collect a fecal sample from Equal the day we observed him with these scars. After analyzing his fecal sample for stress hormones, we discovered that Equal had very high stress levels compared to previous samples collected – unsurprising seeing as he had been hit by a boat! While this event was certainly sad for Equal (although don’t worry – we have seen him many times again in the years after this event looking healthy & normal once again), it was a very fortuitous occurrence for us since we were able to “validate” our stress hormone data relative to the value from Equal when he was clearly stressed out. Find out more about Equal as well as seven other gray whales here!

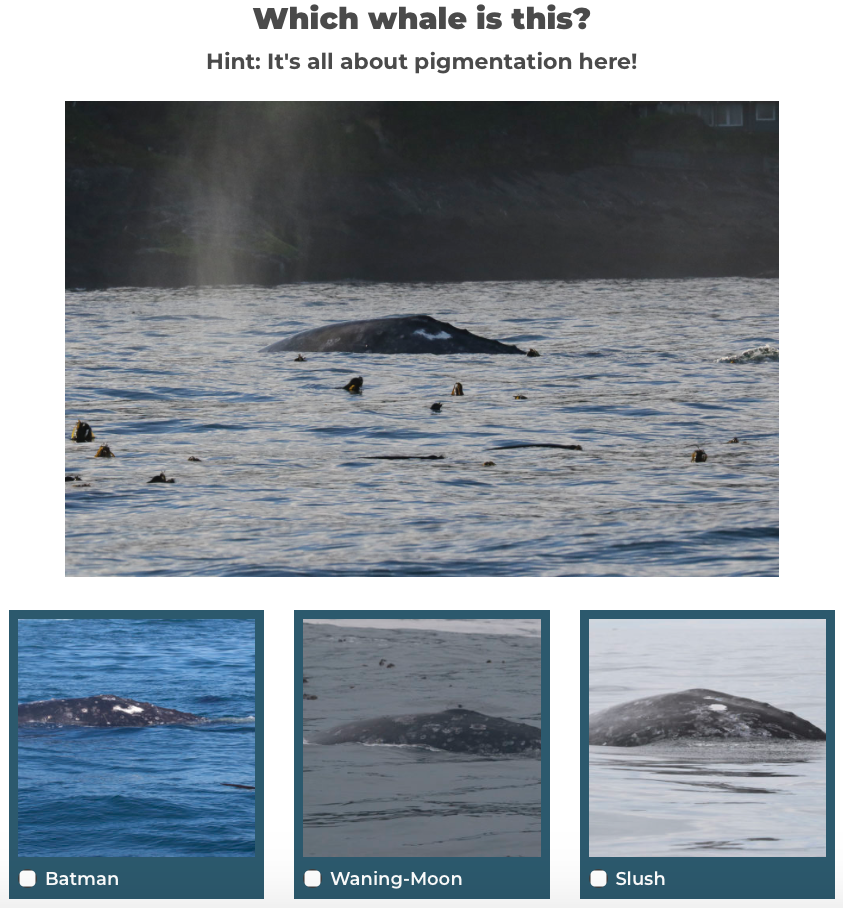

You might be wondering, how we knew that the whale with the boat propeller scar was Equal and how we recognize him again years after the incident. Gray whales have unique pigmentation patterns on their bodies and flukes that allow us to re-identify individuals between years and distinguish them from one another. Additionally, scars, such as those that Equal now carries on his back, can also be useful in telling whales apart. Therefore, we take photographs of every whale we see to match markings and identify whales. This process is called photo ID. Some individuals can have very distinctive markings, such as Roller Skate who has two big white dots on her right side, while others can look more inconspicuous, like Clouds. Therefore, conducting photo ID requires a lot of attention to detail and perseverance. To learn more about the different features we use to identify individuals, check out the “Studying Whales With Photographs” page. Do you think you have what it takes to tell individuals apart? Then try your luck at our photo ID game after!

Unfortunately, these whales do not live in a pristine environment, as is evidenced by Equal’s story. Their main objective during the summer when in Oregon waters is to gain weight (energy stores) by consuming large amounts of prey, which is made more difficult by a number of stressors, including potential fishery entanglements, ocean noise, vessel traffic, and habitat changes. We describe these four stressors on the IndividuWhale website since we are trying to assess the impacts of them on gray whales through our research, however they are certainly not the only stressors that these whales experience. Little is known about the level at which these stressors may have a negative impact on the whales, and how whales react when they experience some of these stressors in concert. The answers to these questions are difficult to tease apart but the GRANITE project is aiming to do so through a framework called Population Consequences of Multiple Stressors (read more about it here). This approach requires a lot of data on a lot of individuals in a population and as you can see from the IndividuWhale website, we are slowly starting to get there! 2022 will certainly bring many more gray whale-themed blogs to this website, and you can share in our journey of learning about the lives of PCFG gray whales by exploring the IndividuWhale website (https://www.individuwhale.com).