Clara Bird, PhD Student, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

When I thought about what doing fieldwork would be like, before having done it myself, I imagined that it would be a challenging, but rewarding and fun experience (which it is). However, I underestimated both ends of the spectrum. I simultaneously did not expect just how hard it would be and could not imagine the thrill of working so close to whales in a beautiful place. One part that I really did not consider was the pre-season phase. Before we actually get out on the boats, we spend months preparing for the work. This prep work involves buying gear, revising and developing protocols, hiring new people, equipment maintenance and testing, and training new skills. Regardless of how many successful seasons came before a project, there are always new tasks and challenges in the preparation phase.

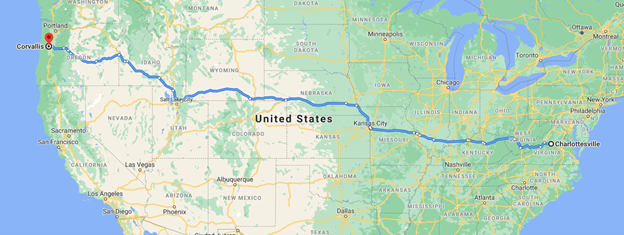

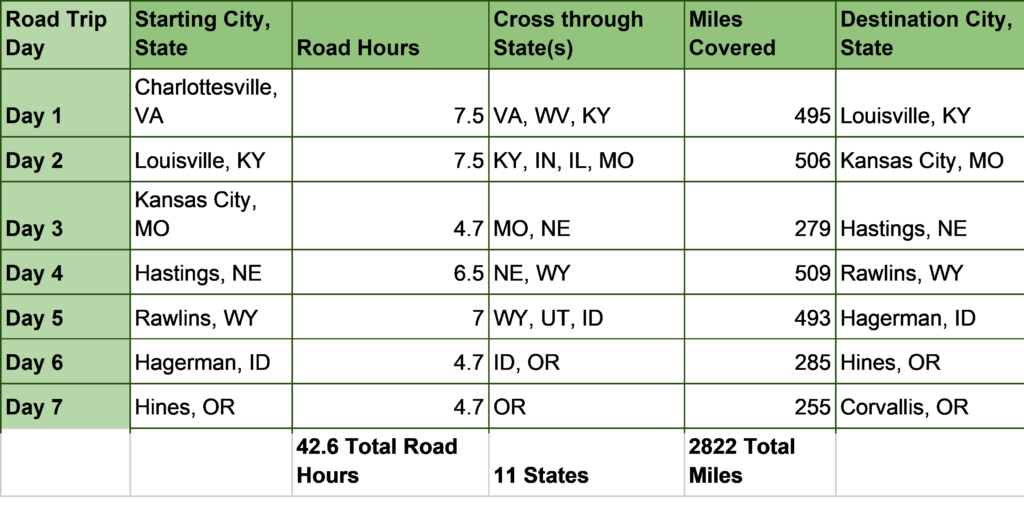

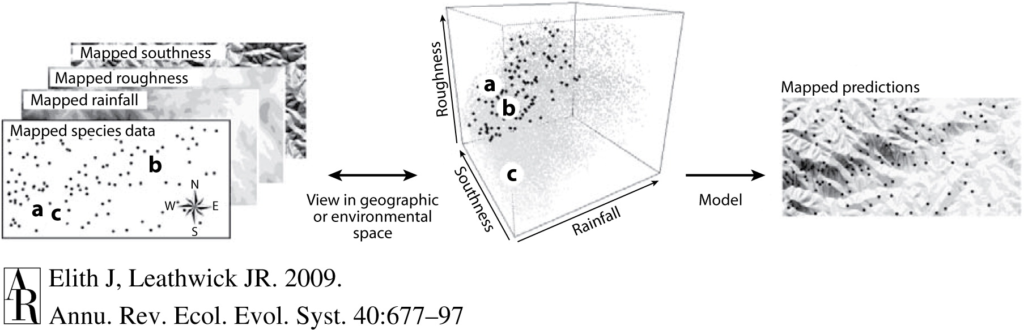

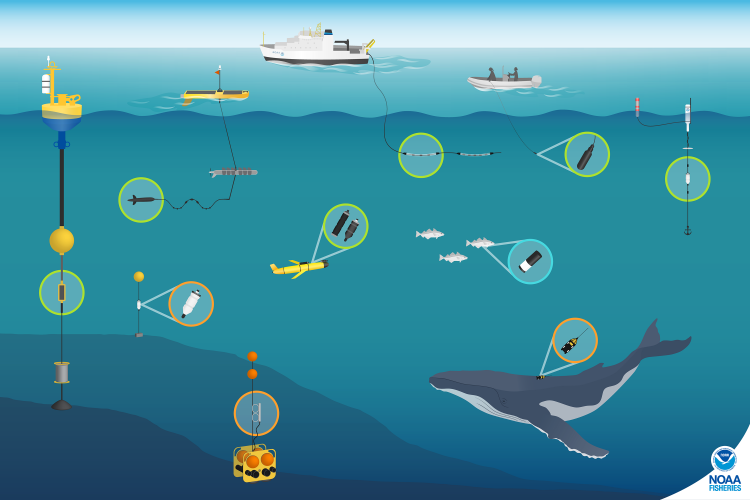

For example, as the GEMM Lab GRANITE project team geared up for its seventh field season, we had a few new components to prepare for. Just to remind you, the GRANITE (Gray whale Response to Ambient Noise Informed by Technology and Ecology) project’s field season typically takes place from June to mid-October of each year. Throughout this time period the field team goes out on a small RHIB (rigid hull inflatable boat), whenever the weather is good enough, to collect photo-ID data, fecal samples, and drone imagery of the Pacific Coast Feeding Group (PCFG) gray whales foraging near Newport, OR, USA. We use the data to assess the health, ecology and population dynamics of these whales, with our ultimate goal being to understand the effect of ambient noise on the population. As previous blogs have described, a typical field day involves long hours on the water looking for whales and collecting data. This year, one of our exciting new updates is that we are going out on two boats for the first part of the field season and starting our season 10 days early (our first day was May 20th). These updates are happening because a National Science Foundation funded seismic survey is being conducted within our study area starting in June. The aim of this survey is to assess geophysical structures but provides us with an opportunity to assess the effect of seismic noise on our study group by collecting data before, during, and after the survey. So, we started our season early in order to capture the “before seismic survey” data and we are using a two-boat approach to maximize our data collection ability.

While this is a cool opportunistic project, implementing the two-boat approach came with a new set of challenges. We had to find a second boat to use, buy a new set of gear for the second boat, figure out the best way to set up our gear on a boat we had not used before, and update our data processing protocols to include data collected from two boats on the same day. Using two boats also means that everyone on the core field team works every day. This core team includes Leigh (lab director/fearless leader), Todd (research assistant), Lisa (PhD student), Ale (new post-doc), and me (Clara, PhD student). Leigh and Todd are our experts in boat driving and working with whales, Todd is our experienced drone pilot, I am our newly certified drone pilot, and Lisa, Ale, and myself are boat drivers. Something I am particularly excited about this season is that Lisa, Ale, and I all have at least one field season under our belts, which means that we get to become more involved in the process. We are learning how to trailer and drive the boats, fly the drones, and handling more of the post-field work data processing. We are becoming more involved in every step of a field day from start to finish, and while it means taking on more responsibility, it feels really exciting. Throughout most of graduate school, we grow as researchers as we develop our analytical and writing skills. But it’s just as valuable to build our skillset for field work. The ocean conditions were not ideal on the first day of the field season, so we spent our first day practicing our field skills.

For our “dry run” of a field day, we went through the process of a typical day, which mostly involved a lot of learning from Leigh and Todd. Lisa practiced her trailering and launching of the boat (figure 1), Ale and Lisa practiced driving the boat, and I practiced flying the drone (figure 2). Even though we never left the bay or saw any whales, I thoroughly enjoyed our dry run. It was useful to run through our routine, without rushing, to get all the kinks out, and it also felt wonderful to be learning in a supportive environment. Practicing new skills is stressful to say the least, especially when there is expensive equipment involved, and no one wants to mess up when they’re being watched. But our group was full of support and appreciation for the challenges of learning. We cheered for successful boat launchings and dockings, and drone landings. I left that day feeling good about practicing and improving my drone piloting skills, full of gratitude for our team and excited for the season ahead.

All the diligent prep work paid off on Saturday with a great first day (figure 3). We conducted five GoPro drops (figure 4), collected seven fecal samples from four different whales (figure 5), and flew four drone flights over three individuals including our star from last season, Sole. Combined, we collected two trifectas (photo-ID images, fecal samples, and drone footage)! Our goal is to get as many trifectas as possible because we use them to study the relationship between the drone data (body condition and behavior) and the fecal sample data (hormones). We were all exhausted after 10 hours on the water, but we were all very excited to kick-start our field season with a great day.

On Sunday, just one boat went out to collect more data from Sole after a rainy morning and I successfully flew over her from launching to landing! We have a long season ahead, but I am excited to learn and see what data we collect. Stay tuned for more updates from team GRANITE as our season progresses!