Clara Bird, Masters Student, OSU Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

The GEMM Lab gray whale team is in the midst of preparing for our fifth field season studying the Pacific Coast Foraging Group (PCFG): whales that forage off the coast of Newport, OR, USA each summer. On any given good weather day from June to October, our team is out on the water in a small zodiac looking for gray whales (Figure 1). When we find a gray whale, we try to collect photo ID data, fecal samples, drone data, and behavioral data. We use the drone data to study both the whale’s body condition and their behavior. In a previous blog, I described ethograms and how I would like to use the behavior data from drone videos to classify behaviors, with the ultimate goal of understanding how gray whale behavior varies across space, time, and by individual. However, this explanation of studying whale behavior is actually a bit incomplete. Before we start fieldwork, we first need to decide how to collect that data.

As observers, we are far from omnipresent and there is no way to know what the animals are doing all of the time. In any environment, scientists have to decide when and where to observe their animals and what behaviors they are interested in recording. In many studies, behavior is recorded live by an observer. In those studies, other limitations need to be taken into account, such as human error and observer fatigue. Collecting behavioral data is particularly challenging in the marine environment. Cetaceans spend most of their lives out of sight from humans, their time at the surface is brief, and when they appear together in large groups it can be very difficult to keep track of who is doing what when. Imagine being in a boat trying to keep track of what three different whales are doing without a pre-determined method – the task could quickly become overwhelming and biased. This is why we need a methodology for collecting and classifying behavior. We cannot study behavior without acknowledging these limitations and the potential biases that come with the methods we choose. Different data collection methods are better suited to address different questions.

The use of drones gives us the ability to record cetacean behavior non-invasively, from a perspective that allows greater observation (Figure 2, Torres et al. 2018), and for later review, which is a significant improvement. However, as we prepare to collect more behavior data, we need to study the methods and understand the benefits and disadvantages of each approach so that we capture the information we need without bias. Altmann (1974) provides a thorough overview of behavioral sampling methods.

Ad libitum behavioral sampling has no structure and occurs when we find a group of whales and just write down everything they are doing. This method is a good first step, however it comes with bias. Without structure, we cannot be sure that there was an equal probability of detecting each kind of behavior; this problem is called detectability bias. This type of bias is an issue if we are trying to answer questions about how often a behavior occurs, or what percent of time is spent in each behavior state. This is a bias to be especially concerned about when it comes to cetaceans because there are many examples of behaviors with different levels of detectability. An extreme example would be the detectability of breaching versus a behavior that takes place under the surface. A breaching whale is easier to spot and more exciting, which could lead to results suggesting that whales breach more often than they do relative to underwater behaviors. While it’s impossible to eliminate detectability bias, other sampling methods employ decision rules to try and reduce its effect. Many decision rules revolve around time, such as setting a minimum or maximum observation time interval. Other time rules involve recording the behavior state at set intervals of time (e.g., every 5 minutes). Setting observation boundaries helps standardize the methods and the data being collected.

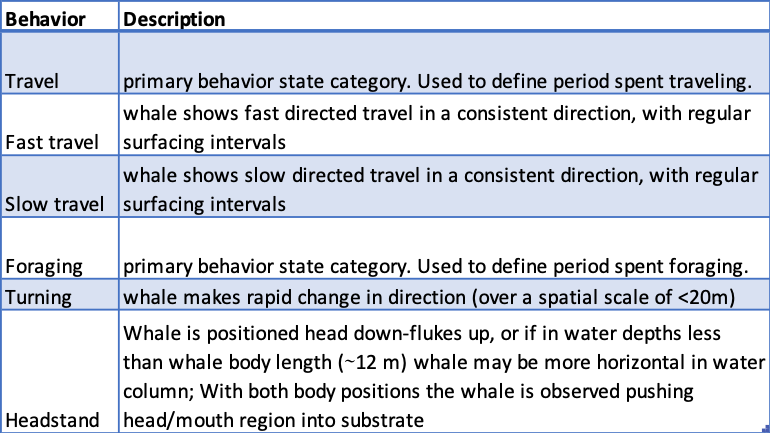

In a structured sampling plan, the first big decision that needs to be addressed is the need to know the duration of behaviors. Point events do not include duration data but can be used to study the frequencies of behaviors. For example, if my research question was “Do whales perform “headstands” in a specific habitat type?”, then I would need point events of headstanding behavior. But, if I wanted to ask, “Do whales spend more time spent headstanding in a specific habitat type than in other habitat types?”, I would need headstanding to be a state event. State events are events with associated duration information and can be used for activity budgets. Activity budgets show how much time an animal spends in each behavior state. Some sampling methods focus on collecting only point events. However, to get the most complete understanding of behavior I think it’s important to collect both. Focal animal follows are another method of collecting more detailed data and is commonly used in cetacean studies.

The explanation of a focal follow method is in the name. We focus on one individual, follow it, and record all of its behaviors. When employing this method, decisions are made about how an individual is chosen and how long it is followed. In some cases, the behavior of this animal is used as a proxy for the behavior of an entire group. I essentially use the focal follow method in my research. While I review drone footage to record behavioral data instead of recording behaviors live in the field, I focus on one individual a time as I go through the videos. To do this I use a software called BORIS (Friard and Gamba 2016) to mark the time of each behavior per individual (Figure 3). If there are three individuals in a video, I’ll review the footage three times to record behaviors once per individual, focusing on each in turn.

While the drone footage brings the advantages of time to review and a better view of the whale, we are constrained by the duration of a flight. Focal follows would ideally last longer than the ~15 minutes of battery life per drone flight. Our previously collected footage gives us snapshots of behavior, and this makes it challenging to compare and analyze durations of behaviors. Therefore, I am excited that we are going to try conducting drone focal follows this summer by swapping out drones when power runs low to achieve longer periods of video coverage of whale behavior. I’ll be able to use these data to move from snapshots to analyzing longer clips and better understanding the behavioral ecology of gray whales. As exciting as this opportunity is, it also presents the challenge of method development. So, I now need to develop decision rules and data collection methods to answer the questions that I have been eagerly asking.

References

Altmann, Jeanne. 1974. “Observational Study of Behavior: Sampling Methods.” Behaviour 49 (3–4): 227–66. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853974X00534.

Friard, Olivier, and Marco Gamba. 2016. “BORIS: A Free, Versatile Open-Source Event-Logging Software for Video/Audio Coding and Live Observations.” Methods in Ecology and Evolution 7 (11): 1325–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12584.

Torres, Leigh G., Sharon L. Nieukirk, Leila Lemos, and Todd E. Chandler. 2018. “Drone up! Quantifying Whale Behavior from a New Perspective Improves Observational Capacity.” Frontiers in Marine Science 5 (SEP). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00319.