By Solène Derville, Postdoc, OSU Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

Ever since I was a teenager, I have been drawn to both arts and sciences. When I decided to go down the path of marine biology and research, I never thought I would one day be led to exploit my artistic skills as well as my scientific interests.

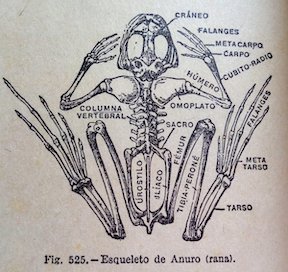

Processing data, coding, analyzing, modeling… these tasks form the core of my everyday work and are what generates my excitement and passion for research. But once a new result has come up, or a new hypothesis has been formed, how boring would it be to keep it for myself? Science is all about communication, exchanges with our peers, with stakeholders, and with the general public. Graphical representations have always been supported in research throughout the history of sciences, and particularly the life sciences (Figure 1).

I have come to realize how much I enjoy this aspect of my work, and also how much I wish I was better prepared for it! In this blogpost I will talk about visual communication in science, and tackle the question of how to make our plots, diagrams, powerpoints, figures, maps, etc. convey information that goes beyond any spoken language? I have compiled a few tips from the design and infographics fields that I think could be reinvested in our scientific communication material.

Plan, order, design

This suggestion may appear like a rather simplistic piece of advice, but any form of communication should start with a plan. What is the name of my project, the goal, and the audience? A scientific conference poster will not be created with the same design as a flyer aimed at the general public, nor will the same tools be used. Libre office powerpoint, canva, inkscape, scribus, R, plotly, GIMP… these are the open-source software I use on a regular basis but there so many more possibilities!

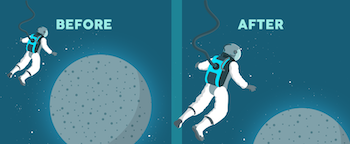

For whatever the type of visual you want to create, there are two major rules that need to be considered. First, embrace the empty space! You may think that you are wasting space that could be filled by all sorts of extremely valuable pieces of information… but this empty space has a purpose all by itself. The empty space brings forward the central elements of your design and will help focus the attention of the viewer toward them (top panel of Figure 2). Second, keep it neat and aligned. Whether you choose to anchor elements to each other or to an invisible grid, pay attention to details so that all images and text in the design from a harmonious whole (bottom panel in Figure 2).

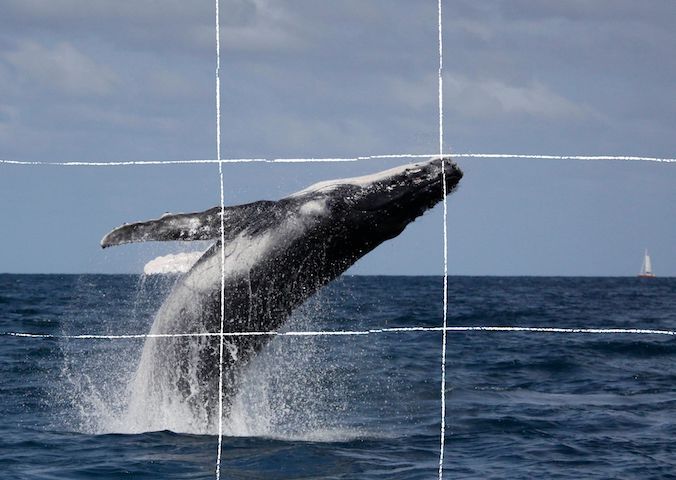

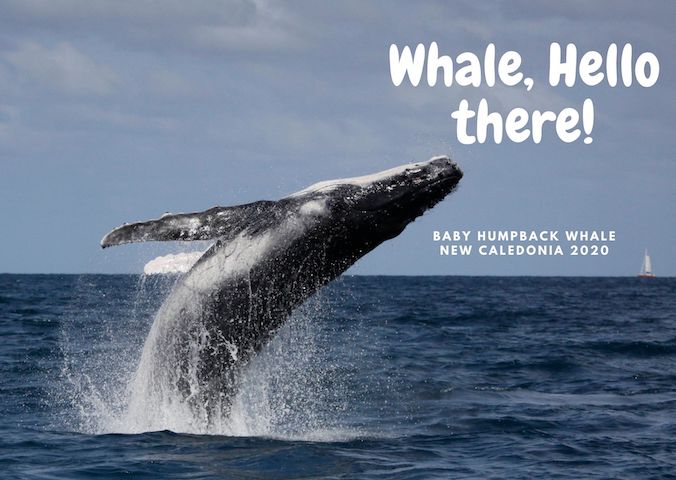

Alignment is also an essential aspect to consider when editing images. More than any text, images will provide the first impression to the viewer and may subjectively communicate ideas in an instant. To make them most effective, images may follow the ‘rule of thirds’. Imagine breaking the image down into thirds, hence creating four directive lines over it (Figure 3). Placing the points of interest of the image at the intersections or along the lines will provide balance and attract the viewer’s attention. In marine mammal science where we often use pictures of animals with the ocean as a background, aligning the horizon along one of these horizontal lines may be a good technique (which I have not followed in Figure 3 though!).

When adding text to images, it is important to not overwhelm illustrations with text by trying to use extensive written material (which happens much too often). I try to keep the text to the strict minimum and let the visuals speak for themselves. When including text over or next to an image, I place the text in the empty spaces, where the eye is drawn to (Figure 4). When using dark or contrasted images, I add a semi-transparent layer in between the text and the image to make my text pop out.

Fonts

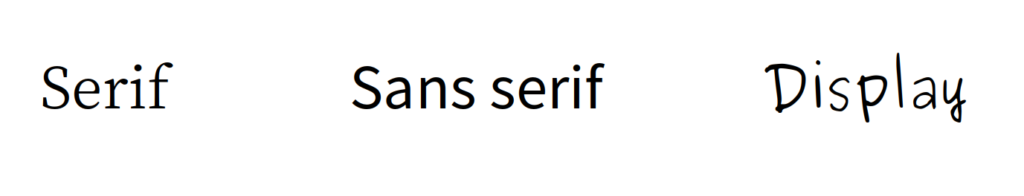

Tired of using Arial, Times and Calibri but don’t know which other font to pick? One good piece of advice I found online was to choose a font that complements the purpose of the design. To do so, it is necessary to choose the message before picking the font. There are three categories of fonts (show in Image 1):

– Serif (classic style designed for books as the little feet at the extremities of the letters guide the eye along the lines of text)

– Sans serif (designed to look clean on digital screen)

– Display (more personality, but to be used in small doses!)

I have also learned that pairing fonts together is often about using opposites (Figure 5). Contrasting fonts are complementary. For instance, it is visually appealing to combine a very bold font with a very light font, or a round font with something tall. And if you need more font choices than the ones provided by your usual software, here is a web repository to freely download thousands of different fonts: https://www.dafont.com

Colors

Colors have inherent meaning that depends on individual cultures. Whether we want it or not, any plot, photo, or diagram that we present to an audience will carry a subliminal message depending on its color palette. So better make it fit with the message!

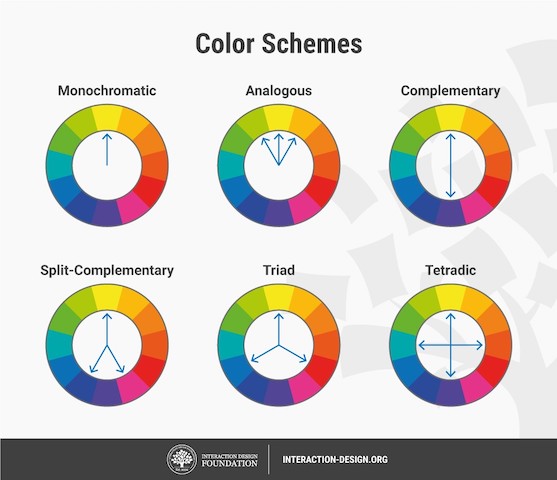

Let us go passed the boring blue shades we have used for all of our marine science presentations so far, and instead open ourselves up to an infinite choice of colors! Color nuances are defined by three things: hue (the color itself), saturation (intensity, whether the color looks more subtle or more vibrant), and value (how dark or light a color is, ranging from white to black). The color wheel helps us visualize the relationships between hues and pick the best associations (Figure 6).

First, pick the main color, the hero color for your design. Choose a cool color (blues and greens) if you want to provide a calming impression or a warm color (reds and yellows) for something more energizing. This basic principle of color theory made me think back on the black/blue dark shaded presentations that I might have attended in the past and had trouble staying awake!

Now, create your color palette, which are the three to four colors that will compose your design, ideally combining some vibrant and some more neutral colors for contrast. For instance, in a publication, a color palette may be used consistently in all plots or figures to represent a set of variables, study areas, or species . Now how do you pick the right complementary colors? The color wheel provides you with a few basic principles that should help you choose a palette (Figure 6). From monochromatic to tetradic schemes, the choice is up to you:

– monochromatic colors: varying values or saturation of a given color picked in the wheel

– analogous colors: colors sitting next to each other in the wheel

– complementary color: colors sitting opposite to each other

If you are an R user, there are a myriad of color palettes available to produce your visuals. One of the most comprehensive list I have found was compiled by Emil Hvitfeldt in github (https://github.com/EmilHvitfeldt/r-color-palettes). For discrete color palettes, I enjoy using the Canva palettes, which are available both in the Canva designs and in R using the ‘canva’ library in combination with the ‘ggplot2’ library (https://www.canva.com/learn/100-color-combinations/).

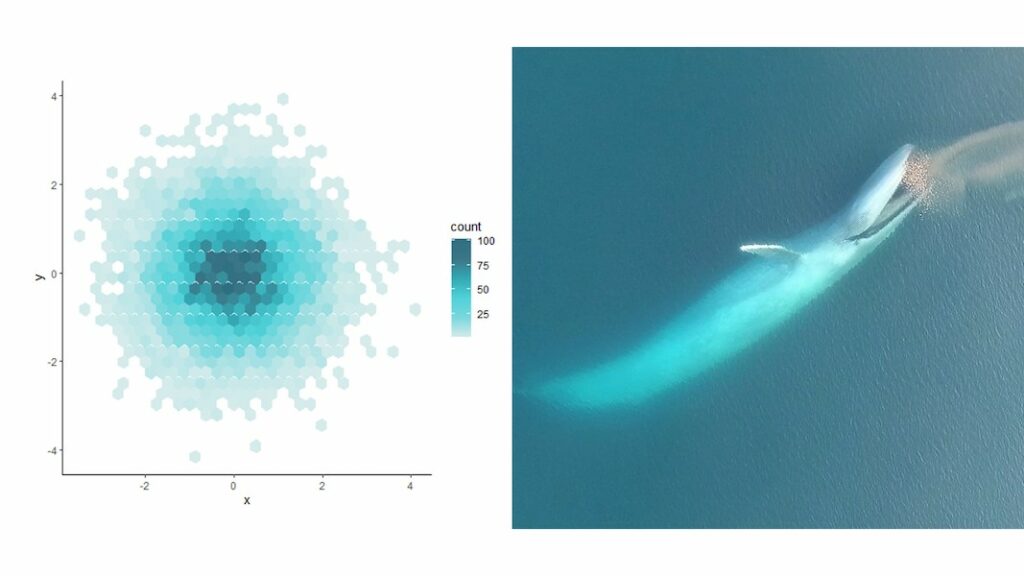

In practice, this means I can produce R plots or maps with color codes that match those I use in my canva presentations or posters. And finally, thumbs up to Dawn and Clara for creating our very own GEMM lab color palette based on whale photos collected in the field (Figure 7: https://github.com/dawnbarlow/musculusColors)!

I hope these few tips help you make your science as look as pretty as it is in your mind!

Sources:

A lot of the material in this blog post was inspired by the free tutorials provided by Canva: https://designschool.canva.com/courses/graphic-design-basics/?lesson=design-to-communicate

About the rule of thirds: https://digital-photography-school.com/rule-of-thirds/

About alignment: https://blog.thepapermillstore.com/design-principles-alignment/