By Lisa Hildebrand, MSc student, OSU Department of Fisheries & Wildlife, Marine Mammal Institute, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

Yodel-Ay-Ee-Ooooo! Hello from the Theyodelers, this year’s Port Orford gray whale foraging ecology field team. In case you were wondering, no, we aren’t hobby yodelers and we don’t plan on becoming them. The team name this year actually has to be attributed to a parent of one of my interns. Shout out to Scott Holt who during the first week of the field season asked his daughter Mattea (our OSU undergraduate intern) whether using a theodolite (the instrument we use to track gray whales from our cliff site) is anything like yodeling. The name was an immediate hit with the team and so the team name discussion was closed fairly early on in the season. Now that I have explained our slightly unconventional team name, let me tell you a little about this year’s team and what has been going on down here on the Oregon south coast so far.

As you can tell from the byline, I (Lisa) am back as the project’s team lead in this, the 6th year of the Port Orford gray whale research and internship project. Going into this year’s field season with two years of experience under my belt has made me feel more confident and comfortable with diving straight back into our fine-scale research with a new team of interns. Yet, I am beginning to realize that no matter how much experience I have, there will always be unforeseeable curve balls thrown at me that I can’t anticipate no matter how prepared or experienced I am. However, my knowledge and experience now certainly inform how I tackle these curve balls and hopefully allow my problem-solving to be better and quicker. I am so thrilled that Leigh and I were able to get the field season approved here in Port Orford despite the ongoing pandemic. There were many steps we had to take and protocols to write and get approved, but it was worth the work. It certainly is strange living in a place that is meant to be your home for six weeks but having to wear a face covering everywhere except your own bedroom. However, mask wearing, frequent hand washing, and disinfecting is a very small price to pay to avoid having a lapse in our gray whale data collected here in Port Orford (and minimize transmission). Doing field research amidst COVID has certainly been a big curve ball this year but, so far, I have been able to handle these added challenges pretty well, especially with a lot of help from my team. Speaking of which, time to introduce the other Theyodelers…

First up, we have Noah Dolinajec. Noah is a fellow graduate student who is currently doing a Master’s in Marine & Lacustrine Science and Management at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel in Brussels, Belgium. While he is attending graduate school in Belgium, Noah is not actually from this European country. In fact, he is a Portlandian! As an Oregonian with a passion for the marine environment, Noah is no stranger to the Oregon coast and has spent quite some time exploring it in the past. Some other things about Noah: before going to college he played semi-professional ice hockey, he is a bit of a birder, and he likes to cook (he and I have been tag-teaming the team cooking this year).

Next, we have Mattea Holt Colberg. As I mentioned before, Mattea is the team’s OSU undergraduate intern this year. By participating in a running-start program at her high school where she took two years of college classes, Mattea entered OSU as a junior at just 18 years old! However, she has decided to somewhat extend her undergraduate career at OSU by completing a dual major in Biology and Music. She plays the piano and the violin (which she brought to Port Orford, but we have yet to be serenaded by her). Mattea has previously conducted field research on killer whales in the Salish Sea and I can tell that she is hoping for killer whales to show up in Port Orford (while not entirely ludicrous, the chance of this happening is probably very, very slim).

Last but certainly not least, is Liz Kelly, our Pacific High School intern from Port Orford. Liz has lived in several different states across the country (I’m talking Kentucky to Florida) and so I am really excited that she currently lives here in Oregon because she has been an absolute joy to have on the team so far. Liz brings a lot of energy and humor to the team, which we have certainly needed whenever those curve balls come flying. Besides her positivity, Liz brings a lot of determination and perseverance and seeing her work through tough situations here already has made me very proud. I really hope this internship provides Liz with the life, STEM, and communication skills she needs to help her succeed in pursuing her goals of doing wildlife research after college. As you may have read in my last blog, our previous high school interns have had successes in being admitted to various colleges to follow their goals, and I feel confident that Liz will be no different. When she is not here at the field station, she can probably be found taking care of and riding one of her four horses (Millie, Maricja, Miera, and Jeanie).

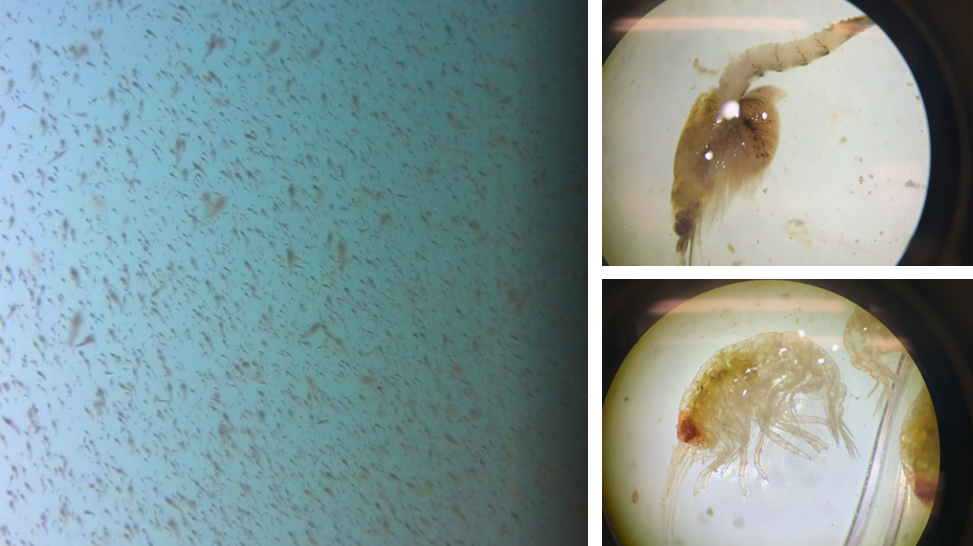

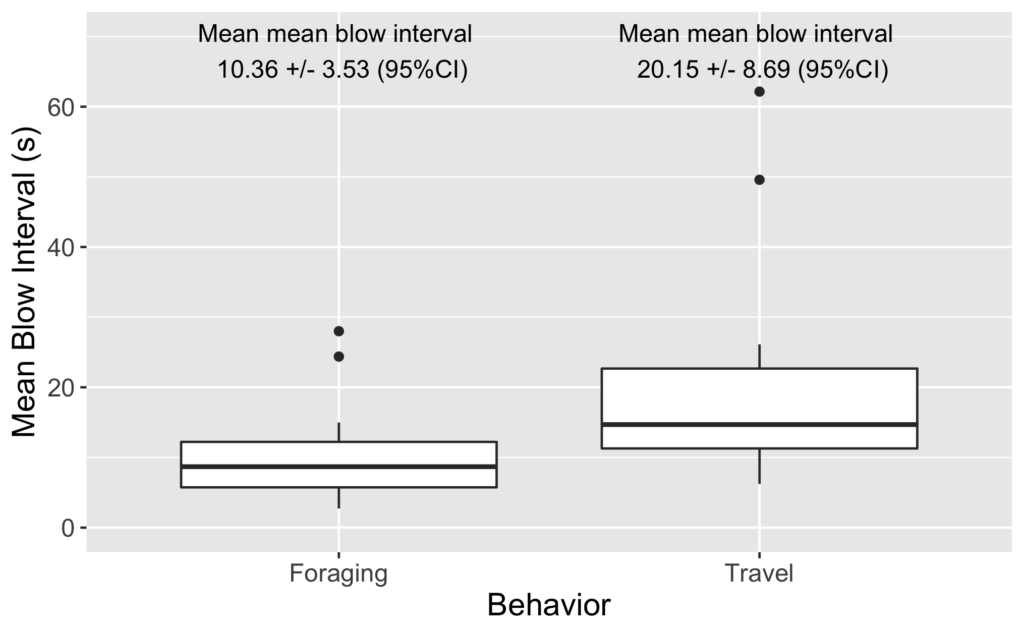

Now that I have introduced the 2020 field team, here is a short play-by-play of what we have been seeing, or perhaps more aptly, not seeing. Our whale sighting numbers have been pretty low so far and when we do see them, they seem to be foraging a little further away from our study site than I am used to seeing in past years. However, this shift in behavior is not entirely surprising to me since our zooplankton net has been coming up pretty empty at our sampling stations. While there are mysids and amphipods scattered here and there, their numbers are in the low 10s when we do our zooplankton ID lab work in the afternoons. These low counts are also reflected by the low densities I am anecdotally seeing on our GoPro drops (Fig 4).

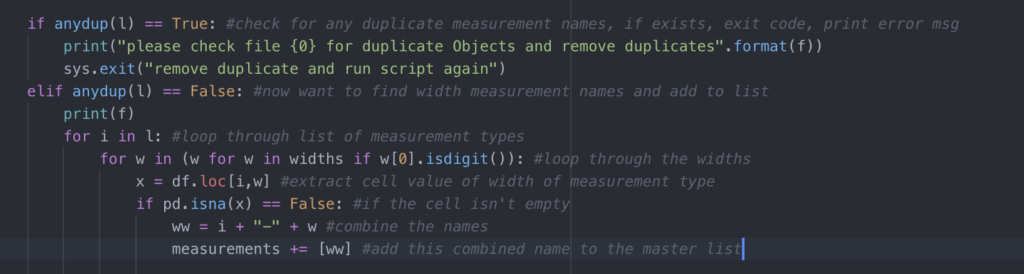

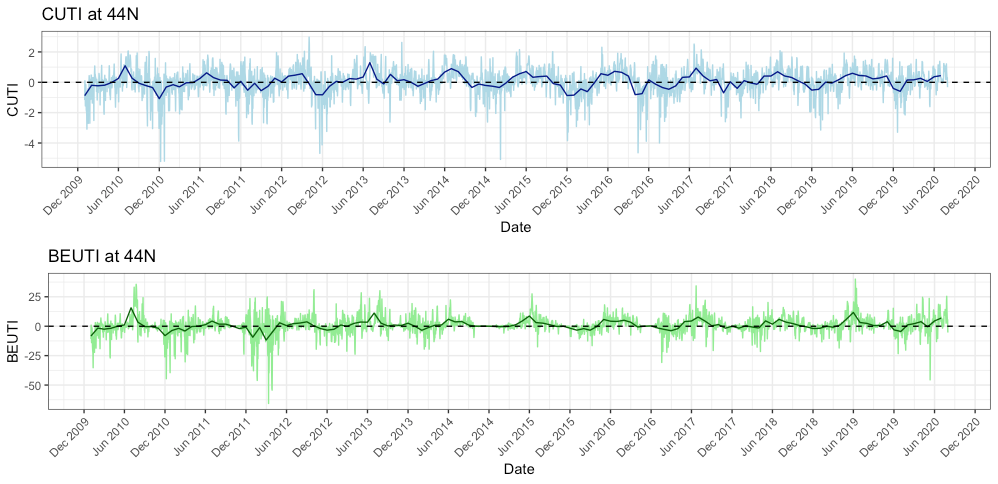

While I am not entirely certain why we are seeing this low prey abundance, I do have some hypotheses. The most likely reason is that this year we experienced some delayed upwelling on our coast. Dawn wrote a great blog about upwelling and wind a few weeks ago and I suggest checking it out to better understand what upwelling is and how it can affect whales (and the whole ecosystem). Typically, we see our peak upwelling occur here in Oregon in May-June. However, if you look at Figure 5 you will see that both the indices remained low at that time this year, whereas in previous years, they were already increasing by May/June.

A delayed upwelling means that there was likely less nutrients in the water to support little critters like zooplankton to start reproducing and increasing their abundances. Simply put, it means our coastal waters appear to be less productive than they usually are at this time of the year. If there is not much prey around (as we have been finding in our two study sites – Mill Rocks and Tichenor Cove), then it makes sense to me why gray whales are not hanging around since there is not much to feed on. Fortunately, the tail of the trend line in Figure 5 is angling upward, which means that the upwelling finally started in June so hopefully the nutrients, zooplankton and whales will follow soon too. In fact, since I wrote the draft of this blog at the end of last week, we have actually seen an increase in the numbers of mysids in our zooplankton net and on our GoPro videos.

We are almost halfway done with the field season already and I cannot believe how quickly it goes by! During the first two weeks we were busy getting familiar with all of our gear and completing First Aid/CPR and kayak paddle & rescue courses. This week the team started the real data collection. We have had some hiccups (we lost our GoPro stick and our backup GoPro stick, but thankfully have already recovered one of them) but overall, we are off to a pretty good start. Now we just need the upwelling to really kick in, for there to be thick layers of mysids, and for the whales to come in close. Over the next three weeks, you will be hearing from Noah, Mattea and Liz as they share their experiences and viewpoints with all of you!