By Leila Lemos1 and Rachel Ann Hauser-Davis2

1PhD candidate, Fisheries and Wildlife Department, OSU

2PhD, CESTEH/ENSP/Fiocruz, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Scientific publishing not only communicates new knowledge, but also is a measure of each scientist’s success: the impact each scientist has on his/her field is often measured by his/her number of publications and the reputation of the journals he/she published in. Therefore, publishing in reputable journals, with a high impact factor, is often essential to get a job, promotion and tenure. So, what is an impact factor?

The impact factor (IF) was first created in the 1960’s and is a measure of a journal’s impact on science, as reflected by the yearly average number of citations to recent articles published in that journal. The IF is used to compare the impact of journals within disciplines. Journals with higher impact factors are deemed as more prestigious and of better quality than those with lower ones.

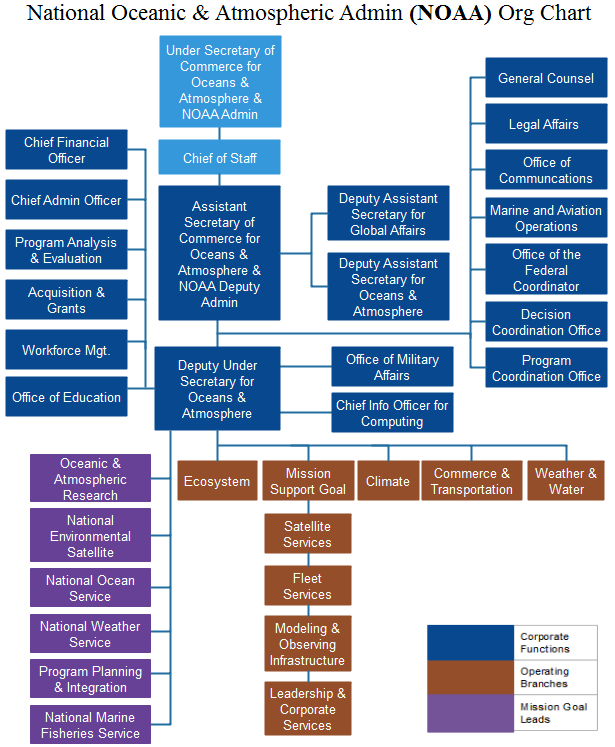

The IF of a journal for any given year is calculated as the number of citations, received in that year, of articles published in that journal during the two preceding years, divided by the total number of articles published in that journal during the two preceding years, as follows:

In recent years, open access (OA) journals have emerged, changing how we perceive publications. However, the role and significance of IF is still present, valuable and used worldwide.

Conventional (non-open access) journals cover publishing costs through access fees, such as subscriptions, site licenses or download charges, which can be paid by universities, research institutions and, sometimes, by individuals. Papers published in OA journals, on the other hand, are distributed online and free of cost. However, there are still publication costs, which are usually paid by the authors. And, open access article processing charges are not cheap, ranging from a few hundred to several thousand dollars, depending on the field (more thoughts on this theme here).

It seems imbalanced that researchers have to pay for their work to be published. They have carried out a study and have obtained results that should be shared with the community. These results should not be treated as a commercial item to be sold. Also, it ends strengthening those who have resources and weakening those who do not have, increasing the division between Northern and Southern hemispheres, and narrowing the knowledge-production system (Burgman 2018).

Thus, a free-of-charge research paper would be interesting for everyone. PeerJ is a good example of a recent OA, free of publishing costs, peer-reviewed, and scholarly journal, that was released in 2013. It’s a totally new model and pushes the boundaries. In addition, there are hybrid journals (i.e., Conservation Biology) that offer both conventional and OA modes, leaving it to the authors to decide what they prefer (Burgman 2018). In many cases, disadvantaged authors might also be able to appeal for waivers. Thus, authors who cannot pay publishing fees might still see their work getting published.

However, this is not how the publishing system typically works. Therefore, researchers need to determine where to publish based on the journal IF and focus/audience, on the different price structures and fees, and whether it is OA or not.

Researchers in general want their articles to be openly accessible for everyone, not just those who can afford to pay the journal for access, so they can increase visibility of their work. Open access can increase the impact/reach of a research paper by facilitating paper downloads, access, and use in other scientific research, which may, in turn, lead to higher citation rate (Eyesenbach 2006).

Higher citation rates would also improve researchers’ H-index: an author-level metric that measures both productivity and citation impact of a scientist or scholar, based on the scientist’s most cited papers and the number of citations that they have received in publications.

The graph below exemplifies the h-index that is based on the maximum value of h such that the given author/journal has published h papers that have each been cited at least h times. In other words, the index is designed to improve with number of publications or citations. The index can only be compared between researchers from same field, as citation conventions might differ widely among different fields.

Source: Wikipedia

However, publishing in an OA journal might easily increase researchers’ H-index and journals’ IF. Many researchers have also considered OA as an “artificial citation enhancer”.

As with any new system, some are opposed to the establishment of the OA system, including researchers, academics, librarians, university administrators, funding agencies, government officials, publishers and editorial staff, among many others (Markin 2017). This opposition claims that OA publishing leads to financial damages to the large publishers worldwide, and, mainly, that this system may damage the peer review system in place today, leading to reduced scientific quality (such as “you pay, you publish” predatory journals that take advantage of the paid system by publishing as fast as possible, without any scientific rigor whatsoever).

However, many reputable journals, such as Elsevier, Springer, Wiley and Blackwell, now offer OA as an option for their established journals. This approach is simply another option for authors, where they may pay if they want for their paper to be available for everyone. Even if this option is available, manuscripts still go through a rigorous peer-review that occurs with both conventional and OA journals. Thus, publishing in OA should be just as rigorous.

Open access papers would be the most “scientifically ethical”, as science is aimed at society, for society, and this type of publishing furthers research reach. However, paying thousands of dollars is sometimes very complicated, as this means less money for fieldwork costs, gears, laboratory analyses, among others.

All in all, OA is a recent development that is changing scientist approach to publication. The future of scientific publication seems uncertain and likely to hold new developments in the near future.

References:

Burgman M. 2018. Open access and academic imperialism. Conservation Biology 0 (0): 1–2. DOI: 10.1111/cobi.13248.

Eysenbach G. 2006. Citation Advantage of Open Access Articles. PLoS Biology 4 (5): e157. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040157. PMC 1459247. PMID 16683865.

Markin P. 2017. The Sustainability of Open Access Publishing Models Past a Tipping Point. Open Science. Retrieved 26 April 2017.