By Lisa Hildebrand, MSc student, OSU Department of Fisheries & Wildlife, Marine Mammal Institute, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

The last two months have been challenging for everyone across the world. While I have also experienced lows and disappointments during this time, I always try to see the positives and to appreciate the good things every day, even if they are small. One thing that I have been extremely grateful and excited about every week is when the clock strikes 9:58 am every Thursday. At that time, I click a Zoom link and after a few seconds of waiting, I am greeted by the smiling faces of the GEMM Lab. This spring term, our Principal Investigator Dr. Leigh Torres is teaching a reading and conference class entitled ‘Cetacean Behavioral Ecology’. Every week there are 2-3 readings (a mix of book chapters and scientific papers) focused on a particular aspect of behavioral ecology in cetaceans. During the first week we took a deep dive into the foundations of behavioral ecology (much of which is terrestrial-based) and we have now transitioned into applying the theories to more cetacean-centric literature, with a different branch of behavior and ecology addressed each week.

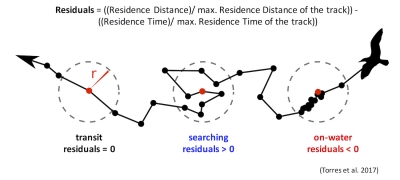

Leigh dedicated four weeks of the class to discussing foraging behavior, which is particularly relevant (and exciting) to me since my Master’s thesis focuses on the fine-scale foraging ecology of gray whales. Trying to understand the foraging behavior of cetaceans is not an easy feat since there are so many variables that influence the decisions made by an individual on where and when to forage, and what to forage on. While we can attempt to measure these variables (e.g., prey, environment, disturbance, competition, an individual’s health), it is almost impossible to quantify all of them at the same time while also tracking the behavior of the individual of interest. Time, money, and unworkable weather conditions are the typical culprits of making such work difficult. However, on top of these barriers is the added complication of scale. We still know so little about the scales at which cetaceans operate on, or, more importantly, the scales at which the aforementioned variables have an effect on and drive the behavior of cetaceans. For instance, does it matter if a predator is 10 km away, or just when it is 1 km away? Is a whale able to sense a patch of prey 100 m away, or just 10 m away? The same questions can be asked in terms of temporal scale too.

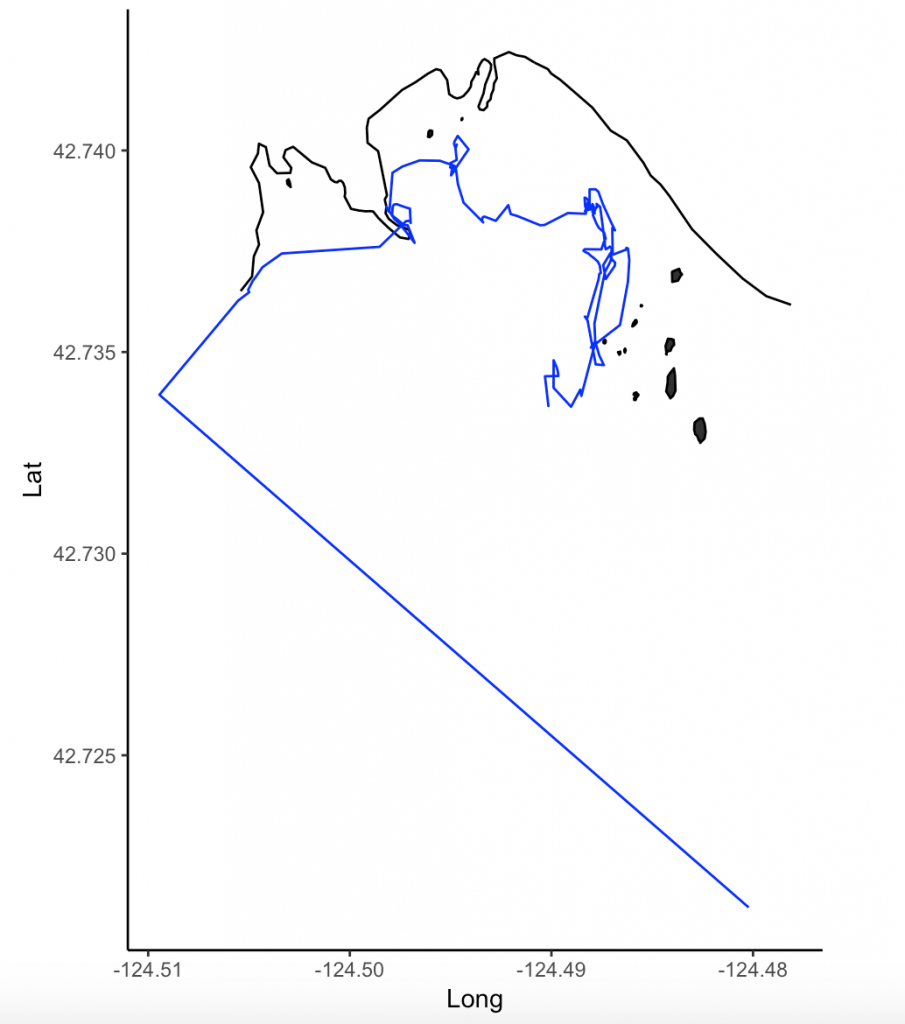

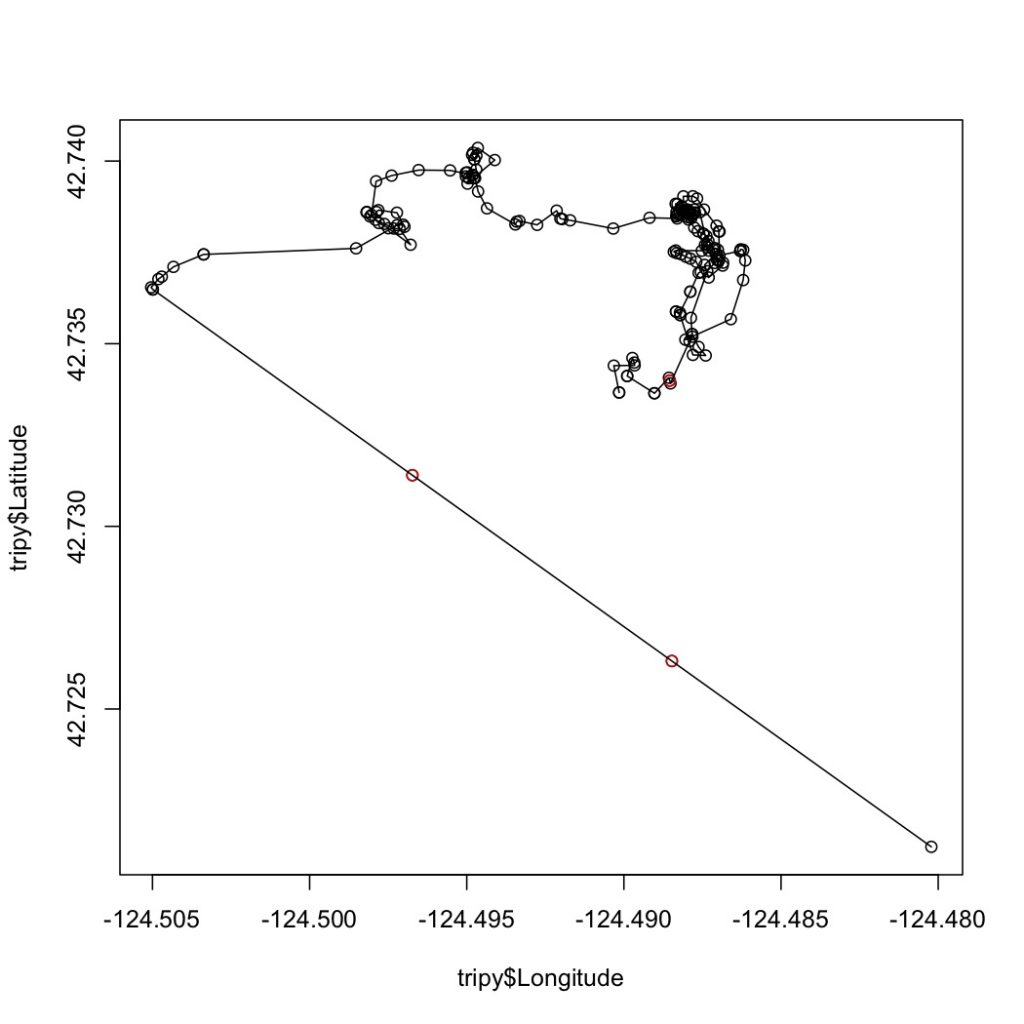

As such, cetacean field work will always involve some compromise in data collection between these factors. A project might address cetacean movements across large swaths of the ocean (e.g., the entire U.S. west coast) to locate foraging hotspots, but it would be logistically complicated to simultaneously collect data on prey distribution and abundance, disturbance and competitors across this same scale at the same time. Alternatively, a project could focus on a small, fixed area, making simultaneous measurements of multiple variables more feasible, but this means that only individuals using the study area are studied. My field work in Port Orford falls into the latter category. The project is unique in that we have high-resolution data on prey (zooplankton) and predators (gray whales), and that these datasets have high spatial and temporal overlap (collected at nearly the same time and place). However, once a whale leaves the study area, I do not know where it goes and what it does once it leaves. As I said, it is a game of compromises and trade-offs.

Ironically, the species and systems that we study also live a life of compromises and trade-offs. In one of this week’s readings, Mridula Srinivasan very eloquently starts her chapter entitled ‘Predator/Prey Decisions and the Ecology of Fear’ in Bernd Würsig’s ‘Ethology and Behavioral Ecology of Odontocetes’ with the following two sentences: “Animal behaviors are governed by the intrinsic need to survive and reproduce. Even when sophisticated predators and prey are involved, these tenets of behavioral ecology hold.”. Every day, animals must walk the tightrope of finding and consuming enough food to survive and ensure a level of fitness required to reproduce, while concurrently making sure that they do not fall prey to a predator themselves. Krebs & Davies (2012) very ingeniously use the idea of economic analysis of costs and benefits to understand foraging behavior (but also behavior in general). While foraging, individuals not only have to assess potential risk (Fig. 1) but also decide whether a certain prey patch or item is profitable enough to invest energy into obtaining it (Fig. 2).

Leigh’s class has been great, not only to learn about foundational theories but to then also apply them to each of our study species and systems. It has been exciting to construct hypotheses based on the readings and then dissect them as a group. As an example, Sih’s 1984 paper on the behavioral response race of predators and prey prompted a discussion on responses of predators and prey to one another and how this affects their spatial distributions. Sih posits that since predators target areas with high prey densities, and prey will therefore avoid areas that predators frequent, their responses are in conflict with one another. Resultantly, there will be different outcomes depending on whichever response dominates. If the predator’s response dominates (i.e. predators are able to seek out areas of high prey density before prey can respond), then predators and prey will have positively correlated spatial distributions. However, if the prey responses dominate, then the spatial distributions of the two should be negatively correlated, as predators will essentially always be ‘one step behind’ the prey. Movement is most often the determinant factor to describe the strength of these relationships.

So, let us think about this for gray whales and their zooplankton prey. The latter are relatively immobile. Even though they dart around in the water column (I have seen them ‘jump’ away from the GoPro when we lower it from the kayak on several occasions; Video 1), they do not have the ability to maneuver away fast or far enough to evade a gray whale predator moving much faster. As such, the predator response will most likely always be the strongest since gray whales operate at a scale that is several orders of magnitude greater than the zooplankton. However, the zooplankton may not be as helpless as I have made them seem. Based on our field observations, it seems that zooplankton often aggregate beneath or around kelp. This behavior could potentially be an attempt to evade predators as the kelp and reef crevices may serve as a refuge. So, in areas with a lot of refuges, the prey response may in fact dominate the relationship between gray whales and zooplankton. This example demonstrates the importance of habitat in shaping predator-prey interactions and behavior. However, we have often observed gray whales perform “bubble blasts” in or near kelp (Video 2). We hypothesize that this behavior could be a foraging tactic to tip the see-saw of predator-prey response strength back into their favor. If this is the case, then I would imagine that gray whales must decide whether the energetic benefit of eating zooplankton hidden in kelp refuges outweighs the energy required to pursue them (Fig. 2). On top of all these choices, are the potential risks and threats of boat traffic, fishing gear, noise, and potential killer whale predation (Fig. 1). Bringing us back to the analogy of economic analysis of costs and benefits to predator-prey relationships. I never realized it so clearly before, but gray whales sure do have a lot of decisions to make in a day!

Trying to tease apart these nuanced dynamics is not easy when I am unable to simply ask my study subjects (gray whales) why they decided to abandon a patch of zooplankton (Were the zooplankton too hard to obtain because they sought refuge in kelp, or was the patch unprofitable because there were too few or the wrong kind of zooplankton?). Or, why do gray whales in Oregon risk foraging in such nearshore coastal reefs where there is high boat traffic (Does their need for food near the reefs outweigh this risk, or do they not perceive the boats as a risk?). So, instead, we must set up specific hypotheses and use these to construct a thought-out and informed study design to best answer our questions (Mann 2000). For the past few weeks, I have spent a lot of time familiarizing myself with spatial packages and functions in R to start investigating the relationships between zooplankton and kelp hidden in the data we have collected over 4 years, to ultimately relate these patterns to gray whale foraging. I still have a long and steep journey before I reach the peak but once I do, I hope to have answers to some of the questions that the Cetacean Behavioral Ecology class has inspired.

Literature cited

Krebs, J. R., and N. B. Davies. 2012. Economic decisions and the individual in Davies, N. B. et al., eds. An introduction to behavioral ecology. John Wiley & Sons, Oxford.

Mann, J. 2000. Unraveling the dynamics of social life: long-term studies and observational methods in Mann, J., ed. Cetacean societies: field studies of dolphins and whales. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Sih, A. 1984. The behavioral response race between predator and prey. The American Naturalist 123:143-150.

Srinivasan, M. 2019. Predator/prey decisions and the ecology of fear in Würsig, B., ed. Ethology and ecology of odontocetes. Springer Nature, Switzerland.