By Rachael Orben

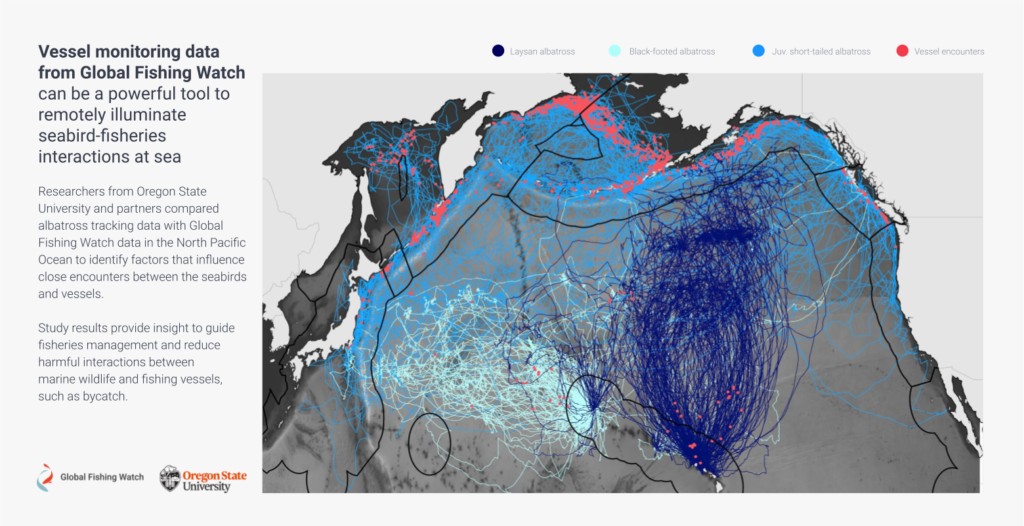

In September of 2016, Leigh Torres, associate professor at Oregon State University, and I attended the 6th International Albatross and Petrel Conference. Somehow, amid all of the science that filled the week, Leigh first saw the Global Fishing Watch fishing map. She shouted with joy. She immediately envisioned a study to assess interactions between seabirds and fishing boats, and started considering a spatial overlap analysis between telemetry tracks of albatross with the Global Fishing Watch database. Such a study could help reduce bycatch, or the incidental catch of non-target species, like seabirds, in fisheries. Five years later, we executed that study in partnership with Global Fishing Watch, one of the first to look at fine-scale overlap between fishing vessels and marine life on the high seas (Orben et al. 2021).

Transparent data means opportunity for analysis

Despite knowing that bycatch from fisheries is a real, significant problem for many albatross populations, we have long struggled to know where birds go, where boats fish, and where the two interact in the vast ocean, especially in largely unregulated international waters. Albatross are long-lived seabirds and 15 out of the 22 species are threatened with extinction. Scientists have been tracking albatross for three decades, but assessing individual seabird encounters with vessels has traditionally been limited by a lack of transparency in fishing activity data. Some seabirds are attracted to fishing vessels because of the bait and offal, but we don’t know the whole story of why some birds approach vessels while others don’t.

When we first put our relatively large datasets together – 9,992 days of albatross tracking data from 150 birds and Global Fishing Watch fishing effort data from 2012-2016 – we weren’t sure what we would find. The ocean is a big place, and so finding where one bird and one vessel overlap is kind of like trying to find a needle in a haystack. Would we have enough encounters between birds and boats for an analysis? Would birds encounter fishing vessels as often as we think?

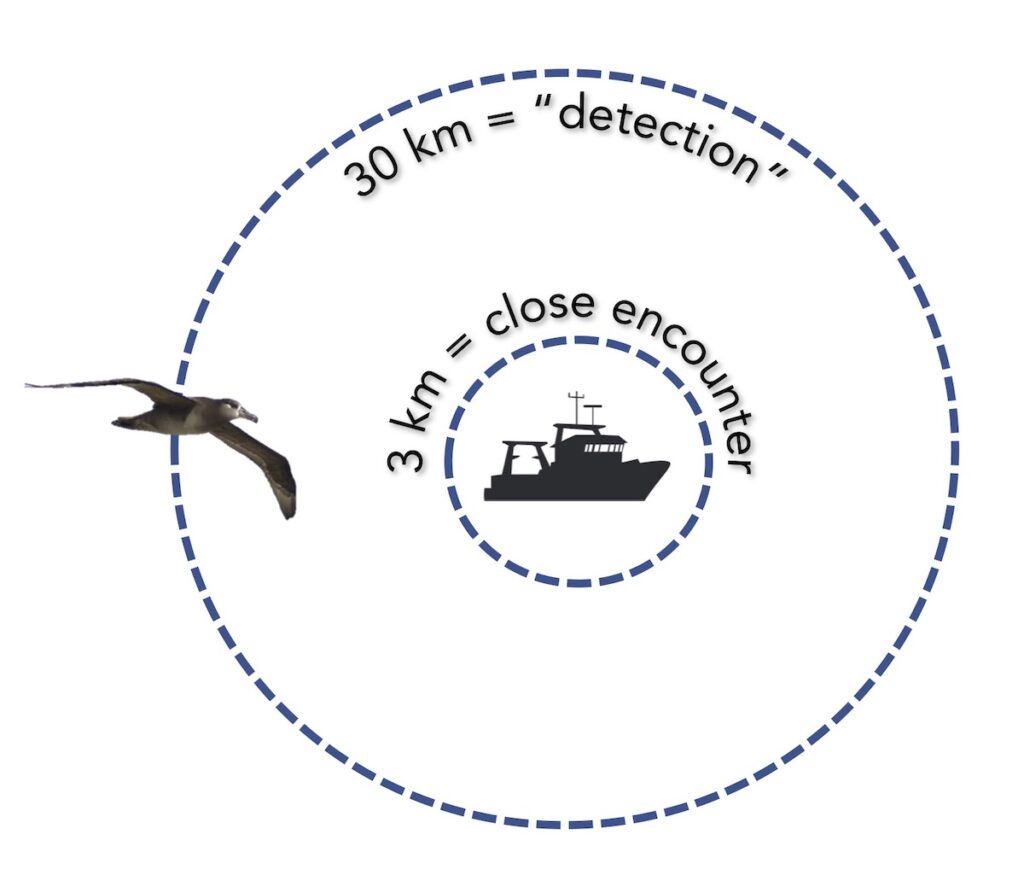

Measuring encounters between albatross and vessels

After overlaying the tracking data with a gridded daily layer of fishing effort, we identified potential encounters between birds and fishing boats. We identified when an albatross could detect a vessel, at a radius or 30 kilometers, and when an albatross had a close encounter with a vessel, within a radius of 3 kilometers (following methods developed in Collet Patrick & Weimerskirch, 2015). Then, we investigated factors that influenced the occurrence and duration of close encounters, considering the bird’s behavior, environmental conditions and habitat, fishing vessel and fisheries characteristics, and temporal variables, such as time of day and month.

Species variation of encounters

We conducted our analysis for three species of albatross that forage in the north Pacific ocean, Laysan albatross, black-footed albatross, and short-tailed albatross.

- Adult black-footed albatrosses approached vessels for a close encounter 61.9 percent of the time they detected a fishing vessel.

- Adult Laysan albatross had close encounters with a fishing boat 35.7 percent of the time they detected a vessel.

- Juvenile short-tailed albatross had a lower frequency of close encounters (28.6 percent),

Understanding close encounters and their duration

Due to a low sample size of encounters, we were unable to investigate the reason for close encounters or their duration for black-footed albatrosses. More tracking data is critical to understand factors influencing the impact of vessels on this vulnerable species.

Laysan albatross were more likely to approach fishing vessels when fishing effort was high, but fishing boat density was low. Laysan albatross also had close encounters with vessels more frequently while they were foraging. Due to sample size, we could not further investigate the reason for the duration of encounters for this species.

Short-tailed albatrosses were also more likely to approach fishing vessels when they were searching for prey, fishing effort was high, and fishing boat density was low. They were more likely to have close encounters with vessels during the day and in habitats with water depths from 75-1500 meters.

Vessel attendance by short-tailed albatrosses was longer when sea surface temperatures were warmer and less productive, and during periods with lower wind speeds.

A useful approach

The information available to fisheries managers in order to reduce bycatch is most often limited to data collected from the perspective of the fishing vessels. Our analysis provides an alternative view – an albatross’ view of when and where boats are encountered in the seascape. While our analysis didn’t specifically look at bycatch, our estimates of proximity between birds and boats can be considered a proxy for increased bycatch risk.

For the endangered short-tailed albatross, bycatch events are few, but they come with high consequences for the bird population and fishing industry. Extending our study in a dynamic ocean management framework to provide an early warning system to predict when short-tailed albatross might make close and longer encounters with fishing vessels could be the next step. Furthermore, our analysis methods to assess when, where and why marine animals interact with fishing vessels can be applied to many other marine species in order to understand and reduce conflicts with fisheries.

This blog was for the Global Fishing Watch blog at globalfishingwatch.org

References

Collet, J., Patrick, S. C., & Weimerskirch, H. (2015). Albatrosses redirect flight towards vessels at the limit of their visual range. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 526, 199–205. http://doi.org/10.3354/meps11233

Orben, RA J Adams, M Hester, SA Shaffer, R Suryan, T Deguchi, K Ozaki, F Sato, LC Young, C Clatterbuck, MG Conners, DA Kroodsma, LG Torres. 2021. Across borders: External factors and prior behavior influence North Pacific albatross associations with fishing vessels. Journal of Applied Ecology. https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1365-2664.13849