Rachel Kaplan, PhD student, Oregon State University College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences and Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

I always have a small crisis before heading into the field, whether for a daytrip or a several-month stint. I’m always dying to go – up until the moment when it is actually time to leave, and I decide I’d rather stay home, keep working on whatever has my current focus, and not break my comfortable little routine.

Preparing to leave on the most recent Northern California Current (NCC) cruise was no different. And just as always, a few days into the cruise, I forgot about the rest of my life and normal routines, and became totally immersed in the world of the ship and the places we went. I learned an exponential amount while away. Being physically in the ecosystem that I’m studying immediately had me asking more, and better, questions to explore at sea and also bring back to land.

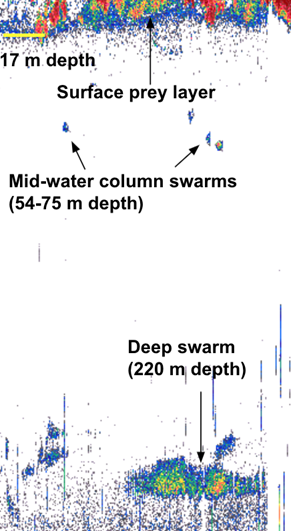

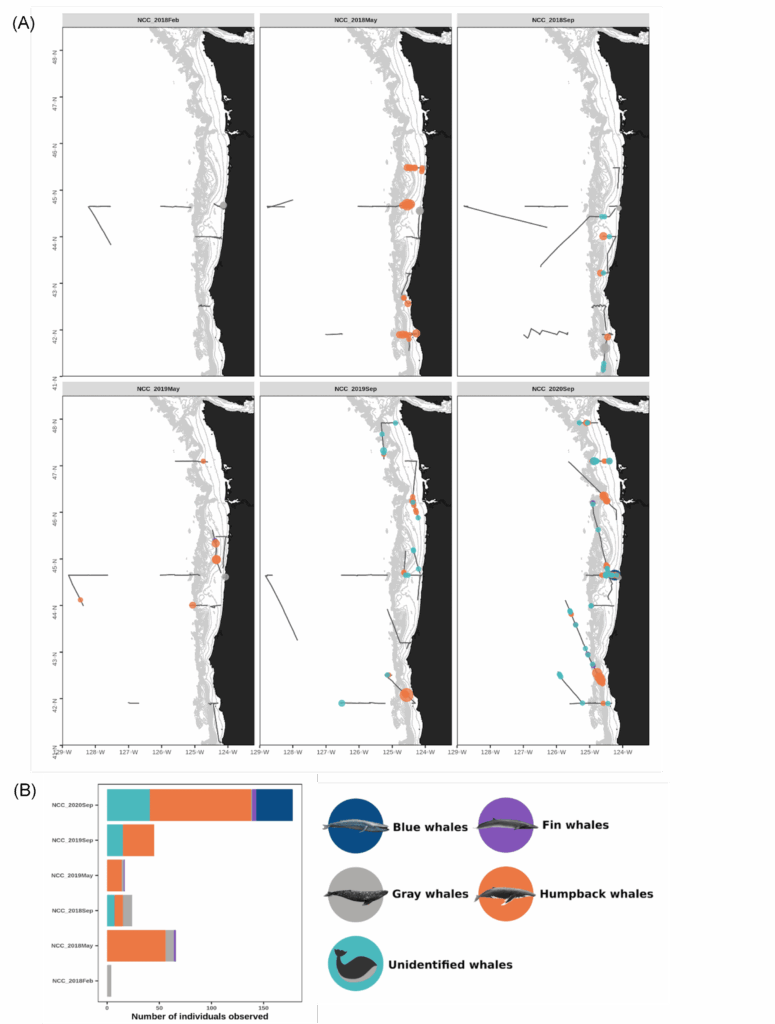

Many of these questions and realizations centered on predator-prey relationships between krill and whales at fine spatial scales. We know that distributions of prey species are a big factor in structuring whale distributions in the ocean, and one of our goals on this cruise was to observe these relationships more closely. The cruise offered an incredible opportunity to experience these relationships in real time: while my labmates Dawn and Clara were up on the flying bridge looking for whales, I was down in the acoustics lab, watching incoming echosounder data in order to identify krill aggregations.

We used radios to stay in touch with what we were each seeing in real time, and learned quickly that we tended to spot whales and krill almost simultaneously. Experiencing this coherence between predator and prey distributions felt like a physical manifestation of my PhD. It also affirmed my faith in one of our most basic modeling assumptions: that the backscatter signals captured in our active acoustic data are representative of the preyscape that nearby whales are experiencing.

Being at sea with my labmates also catalyzed an incredible synthesis of our different types of knowledge. Because of the way that I think about whale distributions, I usually just focus on whether a certain type of whale is present or not while surveying. But Clara, with her focus on cetacean behavior, thinks in a completely different way from me. She timed the length of dives and commented on the specific behaviors she noticed, bringing a new level of context to our observations. Dawn, who has been joining these cruises for five years now, shared her depth of knowledge built through returning to these places again and again, helping us understand how the system varies through time.

One of the best experiences of the cruise for me was when we conducted a targeted net tow in an area of foraging humpbacks on the Heceta Head Line off the central Oregon coast. The combination of the krill signature I was seeing on the acoustics display, and the radio reports from Dawn and Clara of foraging dives, convinced me that this was an opportunity for a net tow, if possible, to see exactly what zooplankton was in the water near the whales. Our chief scientist, Jennifer Fisher, and the ship’s officers worked together to quickly turn the ship around and get a net in the water, in an effort to catch krill from the aggregation I had seen.

This unique opportunity gave me a chance to test my own interpretation of the acoustics data, and compare what we captured in the net with what I expected from the backscatter signal. It also prompted me to think more about the synchrony and differences between what is captured by net tows and echosounder data, two primary ways for looking at whale prey.

Throughout the entire cruise, the opportunity to build my intuition and notice ecological patterns was invaluable. Ecosystem modeling gives us the opportunity to untangle incredible complexity and put dynamic relationships in mathematical terms, but being out on the ocean provides the chance to develop a feel for these relationships. I’m so glad to bring this new perspective to my next round of models, and excited to continue trying to tease apart fine-scale dynamics between whales and krill.

Did you enjoy this blog? Want to learn more about marine life, research, and conservation? Subscribe to our blog and get a weekly message when we post a new blog. Just add your name and email into the subscribe box below.