By KC Bierlich, Postdoctoral Scholar, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, & Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

With the GRANITE field season officially over, we are now processing all of the data we collected this summer. For me, I am starting to go through all the drone videos to take snapshots of each whale to measure their body condition. As I go through these videos, I am reflecting on the different experiences I am fortunate enough to have with flying different drones, in different environments, over different species of baleen whales: blue, humpback, Antarctic minke, and now gray whales. Each of these species have a different morphological design and body shape (Woodward et al., 2006), which leads to different behaviors that are noticeable from the drone. Drones create immense opportunity to learn how whales thrive in their natural environments [see previous blog for a quick history], and below are some of my memories from above.

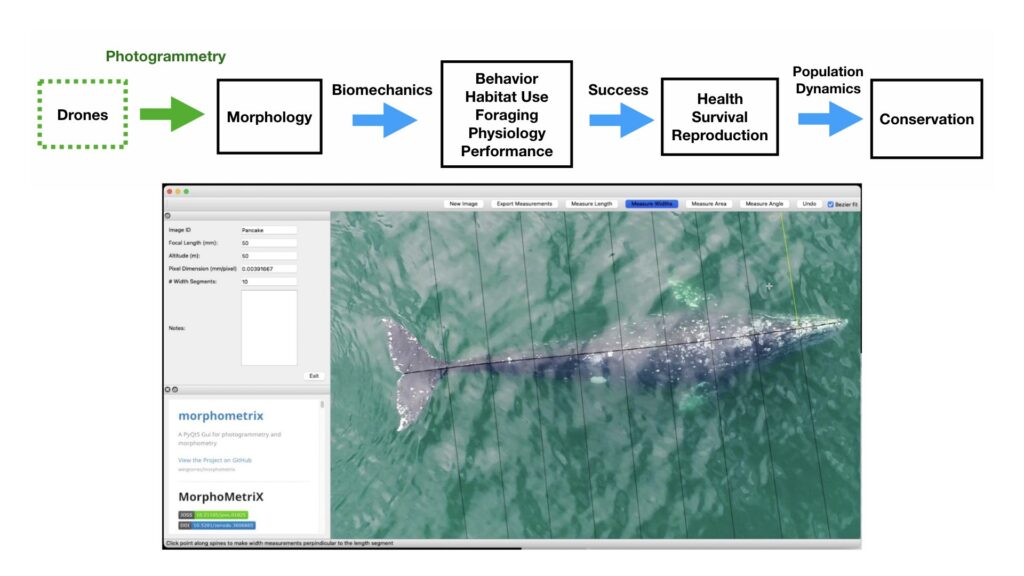

I first learned how drones could be used to study the morphology and behavior of large marine mammals during my master’s degree at Duke University, and was inspired by the early works of John Durban (Durban et al., 2015, 2016) Fredrick Christiansen (Christiansen et al., 2016) and Leigh Torres (Torres et al., 2018). I immediately recognized the value and utility of this technology as a new tool to better monitor the health of marine mammals. This revelation led me to pursue a PhD with the Duke University Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing (MaRRS) Lab led by Dr. Dave Johnston where I helped further develop tools and methods for collecting drone-based imagery on a range of species in different habitats.

When flying drones over whales, there are a lot of moving parts; you’re on a boat that is moving, flying something that is moving, following something that is moving. These moving elements are a lot to think about, so I trained hard, so I did not have to think about each step and flying felt intuitive and natural. I did not grow up playing video games, so reaching this level of comfort with the controls took a lot of practice. I practiced for hours over the course of months before my first field excursion and received some excellent mentorship and training from Julian Dale, the lead engineer in the MaRRS Lab. Working with Julian and the many hours of training helped me establish a solid foundation in my piloting skills and feel confident working in various environments on different species.

Blue whales offshore of Monterey, California.

In 2017 and 2018 I was involved in collaborative project with the MaRRS Lab and Goldbogen Lab at Stanford University, where we tagged and flew drones over blue whales offshore of Monterey, California. We traveled about an hour offshore and reliably found groups of blue whales actively feeding. Working offshore typically brought a large swell, which can often make landing the drone back into your field partner’s hands tricky as everything is bobbing up and down with the oscillations of the swell. Fortunately, we worked from a larger research vessel (~56 ft) and quickly learned that landing the drone in the stern helped dampen the effects of bobbing up and down. The blue whales we encountered often dove to a depth of around 200 m for about 20-minute intervals, then come to the surface for only a few minutes. This short surface period provided only a brief window to locate the whale once it surfaced and quickly fly over it to collect the imagery needed before it repeated its dive cycle. We learned to be patient and get a sense of the animal’s dive cycle before launch in order to time our flights so the drone would be in the air a couple of minutes before the whale surfaced.

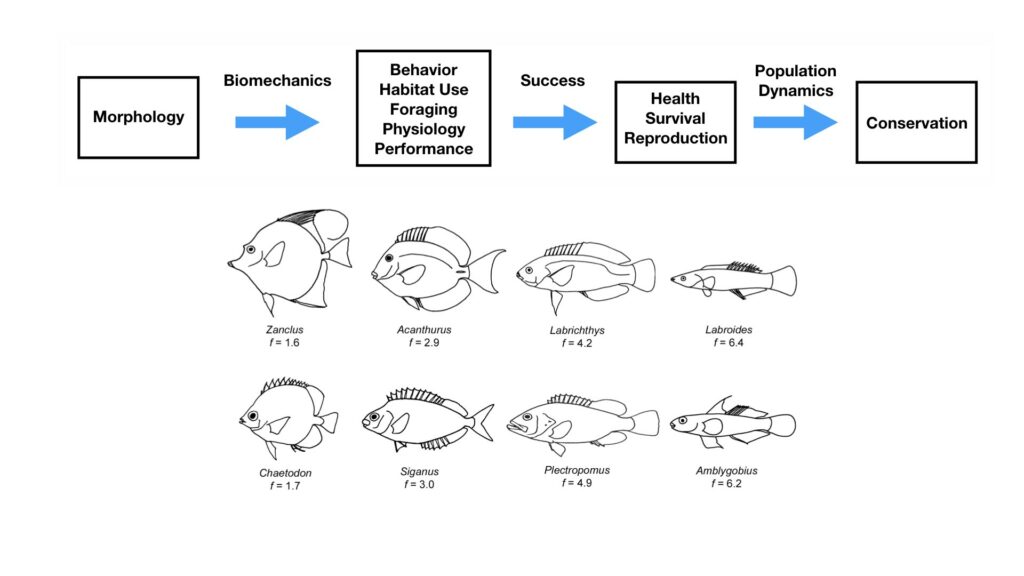

Once over the whales, the streamlined body of the blue whales was noticeable, with their small, high aspect ratio flippers and fluke that make them so well adapted for fast swimming in the open ocean (Fig. 1) (Woodward et al., 2006). I also noticed that because these whales are so large (often 21 – 24 m), I often flew at higher altitudes to be able fit them within the field of view of the camera. It was also always shocking to see how small the tagging boat (~8 m) looked when next to Earth’s largest creatures.

Antarctic minke whales and humpback whales along the Western Antarctic PeninsulaA lot of the data included in my dissertation came from work along the Western Antarctic Peninsula (WAP), which had a huge range of weather conditions, from warm and sunny days to cold and snowy/foggy/rainy/windy/icy days. A big focus was often trying to keep my hands warm, as it was often easier to fly without gloves in order to better feel the controls. One of the coldest days I remember was late in the season in mid-June (almost winter!) in Wilhemina Bay where ice completely covered the bay in just a couple hours, pushing the whales out into the Gerlache Strait; I suspect this was the last ice-free day of the season. Surprisingly though, the WAP also brought some of the best conditions I have ever flown in. Humpback and Antarctic minke whales are often found deep within the bays along the peninsula, which provided protection from the wind. So, there were times where it would be blowing 40 mph in the Gerlache Strait, but calm and still in the bays, such as Andvord Bay, which allowed for some incredible conditions for flying. Working from small zodiacs (~7 m) allowed us more maneuverability for navigating around or through the ice deep in the bays (Fig. 2)

Flying over Antarctic minke whale was always rewarding, as they are very sneaky and can quickly disappear under ice flows or in the deep, dark water. Flying over them often felt like a high-speed chase, as their small streamlined bodies makes them incredibly quick and maneuverable, doing barrel rolls, quick banked turns, and swimming under and around ice flows (Fig. 3). There would often be a group between 3-7 individuals and it felt like they were playing tag with each other – or perhaps with me!

Humpbacks displayed a wide range of behaviors along the WAP. Early in the season they continuously fed throughout the entire day, often bubble net feeding in groups typically of 2-5 animals (Fig. 4). For as large as they are, it was truly amazing to see how they use their pectoral fins to perform quick accelerations and high-speed maneuvering for tight synchronized turns to form bubble nets, which corral and trap their krill, their main food source (Fig. 4) (Woodward et al., 2006). Later in the season, humpbacks switched to more resting behavior in the day and mostly fed at night, taking advantage of the diel vertical migration of krill. This behavior meant we often found humpbacks snoozing at the surface after a short dive, as if they were in a food coma. They also seemed to be more curious and playful with each other and with us later in the season (Fig. 5).

We also encountered a lot of mom and calf pairs along the WAP. Moms were noticeably skinny compared to their plump calf in the beginning of the season due to the high energetic cost of lactation (Fig. 6). It is important for moms to regain this lost energy throughout the feeding season and begin to wean their calves. I often saw moms refusing to give milk to their nudging calf and instead led teaching lessons for feeding on their own.

Gray whales off Newport, Oregon

All of these past experiences helped me quickly get up to speed and jump into action with the GRANITE field team when I officially joined the GEMM Lab this year in June. I had never flown a DJI Inspire quadcopter before (the drone used by the GEMM Lab), but with my foundation piloting different drones, some excellent guidance from Todd and Clara, and several hours of practice to get comfortable with the new setup, I was flying over my first gray whale by day three of the job.

The Oregon coast brings all sorts of weather, and some days I strangely found myself wearing a similar number of layers as I did in Antarctica. Fog, wind, and swell could all change within the hour, so I learned to make the most of weather breaks when they came. I was most surprised by how noticeably different gray whales behave compared to the blue, Antarctic minke, and humpback whales I had grown familiar with watching from above. For one, it is absolutely incredible to see how these huge whales use their low-aspect ratio flippers and flukes (Woodward et al., 2006) to perform low-speed, highly dynamic maneuvers to swim in very shallow water (5-10 m) so close to shore (<1m sometimes!) and through kelp forest or surf zones close to the beach. They have amazing proprioception, or the body’s ability to sense its movement, action, and position, as gray whales often use their pectoral fins and fluke to stay in a head standing position (see Clara Bird’s blog) to feed in the bottom sediment layer, all while staying in the same position and resisting the surge of waves that could smash them against the rocks (Video 1) . It is also remarkable how the GEMM Lab knows each individual whale based on natural skin marks, and I started to get a better sense of each whale’s behavior, including where certain individuals typically like to feed, or what their dive cycle might be depending on their feeding behavior.

I feel very fortunate to be a part of the GRANITE field team and to contribute to data collection efforts. I look forward to the data analysis phase to see what we learn about how the morphology and behavior of these gray whales to help them thrive in their environment.

References:

Christiansen, F., Dujon, A. M., Sprogis, K. R., Arnould, J. P. Y., and Bejder, L. (2016).Noninvasive unmanned aerial vehicle provides estimates of the energetic cost of reproduction in humpback whales. Ecosphere 7, e01468–18.

Durban, J. W., Fearnbach, H., Barrett-Lennard, L. G., Perryman, W. L., & Leroi, D. J. (2015). Photogrammetry of killer whales using a small hexacopter launched at sea. Journal of Unmanned Vehicle Systems, 3(3), 131-135.

Durban, J. W., Moore, M. J., Chiang, G., Hickmott, L. S., Bocconcelli, A., Howes, G., et al.(2016). Photogrammetry of blue whales with an unmanned hexacopter. Mar. Mammal Sci. 32, 1510–1515.

Torres, L. G., Nieukirk, S. L., Lemos, L., & Chandler, T. E. (2018). Drone up! Quantifying whale behavior from a new perspective improves observational capacity. Frontiers in Marine Science, 5, 319.

Woodward, B. L., Winn, J. P., and Fish, F. E. (2006). Morphological specializations of baleen whales associated with hydrodynamic performance and ecological niche. J. Morphol. 267, 1284–1294.