Clara Bird, Masters Student, OSU Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

The GEMM lab recently completed its fourth field season studying gray whales along the Oregon coast. The 2019 field season was an especially exciting one, we collected rare footage of several interesting gray whale behaviors including GoPro footage of a gray whale feeding on the seafloor, drone footage of a gray whale breaching, and drone footage of surface feeding (check out our recently released highlight video here). For my master’s thesis, I’ll use the drone footage to analyze gray whale behavior and how it varies across space, time, and individual. But before I ask how behavior is related to other variables, I need to understand how to best classify the behaviors.

How do we collect data on behavior?

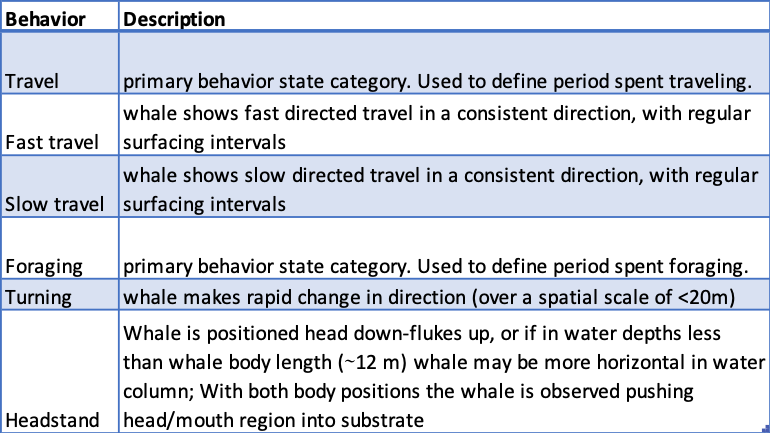

One of the most important tools in behavioral ecology is an ‘ethogram’. An ethogram is a list of defined behaviors that the researcher expects to see based on prior knowledge. It is important because it provides a standardized list of behaviors so the data can be properly analyzed. For example, without an ethogram, someone observing human behavior could say that their subject was walking on one occasion, but then say strolling on a different occasion when they actually meant walking. It is important to pre-determine how behaviors will be recorded so that data classification is consistent throughout the study. Table 1 provides a sample from the ethogram I use to analyze gray whale behavior. The specificity of the behaviors depends on how the data is collected.

In marine mammal ecology, it is challenging to define specific behaviors because from the traditional viewpoint of a boat, we can only see what the individuals are doing at the surface. The most common method of collecting behavioral data is called a ‘focal follow’. In focal follows an individual, or group, is followed for a set period of time and its behavioral state is recorded at set intervals. For example, a researcher might decide to follow an animal for an hour and record its behavioral state at each minute (Mann 1999). In some studies, they also recorded the location of the whale at each time point. When we use drones our methods are a little different; we collect behavioral data in the form of continuous 15-minute videos of the whale. While we collect data for a shorter amount of time than a typical focal follow, we can analyze the whole video and record what the whale was doing at each second with the added benefit of being able to review the video to ensure accuracy. Additionally, from the drone’s perspective, we can see what the whales are doing below the surface, which can dramatically improve our ability to identify and describe behaviors (Torres et al. 2018).

Categorizing Behaviors

In our ethogram, the behaviors are already categorized into primary states. Primary states are the broadest behavioral states, and in my study, they are foraging, traveling, socializing, and resting. We categorize the specific behaviors we observe in the drone videos into these categories because they are associated with the function of a behavior. While our categorization is based on prior knowledge and critical evaluation, this process can still be somewhat subjective. Quantitative methods provide an objective interpretation of the behaviors that can confirm our broad categorization and provide insight into relationships between categories. These methods include path characterization, cluster analysis, and sequence analysis.

Path characterization classifies behaviors using characteristics of their track line, this method is similar to the RST method that fellow GEMM lab graduate student Lisa Hildebrand described in a recent blog. Mayo and Marx (1990) analyzed the paths of surface foraging North Atlantic Right Whales and were able to classify the paths into primary states; they found that the path of a traveling whale was more linear and then paths of foraging or socializing whales that were more convoluted (Fig 1). I plan to analyze the drone GPS track line as a proxy for the whale’s track line to help distinguish between traveling and foraging in the cases where the 15-minute snapshot does not provide enough context.

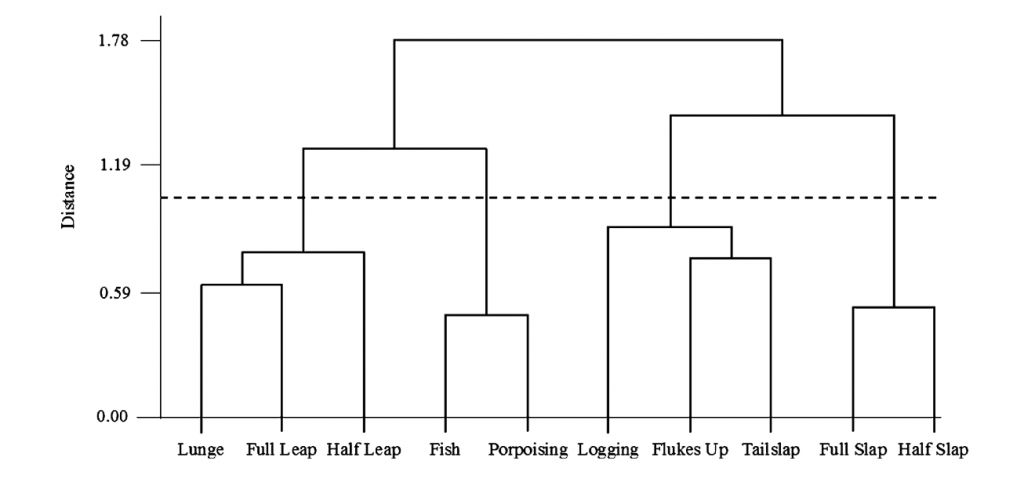

Cluster analysis looks for natural groupings in behavior. For example, Hastie et al. (2004) used cluster analysis to find that there were four natural groupings of bottlenose dolphin surface behaviors (Fig. 2). I am considering using this method to see if there are natural groupings of behaviors within the foraging primary state that might relate to different prey types or habitat. This process is analogous to breaking human foraging down into sub-categories like fishing or farming by looking for different foraging behaviors that typically occur together.

Lastly, sequence analysis also looks for groupings of behaviors but, unlike cluster analysis, it also uses the order in which behaviors occur. Slooten (1994) used this method to classify Hector’s dolphin surface behaviors and found that there were five classes of behaviors and certain behaviors connected the different categories (Fig. 3). This method is interesting because if there are certain behaviors that are consistently in the same order then that indicates that the order of events is important. What function does a specific sequence of behaviors provide that the behaviors out of that order do not?

Think about harvesting fruits and vegetables from a garden: the order of how things are done matters and you might use different methods to harvest different kinds of produce. Without knowing what food was being harvested, these methods could detect that there were different harvesting methods for different fruits or veggies. By then studying when and where the different methods were used and by whom, we could gain insight into the different functions and patterns associated with the different behaviors. We might be able to detect that some methods were always used in certain habitat types or that different methods were consistently used at different times of the year.

Behavior classification methods such as these described provide a more refined and detailed analysis of categories that can then be used to identify patterns of gray whale behaviors. While our ultimate goal is to understand how gray whales will be affected by a changing environment, a comprehensive understanding of their current behavior serves as a baseline for that future study.

References

Burnett, J. D., Lemos, L., Barlow, D., Wing, M. G., Chandler, T., & Torres, L. G. (2019). Estimating morphometric attributes of baleen whales with photogrammetry from small UASs: A case study with blue and gray whales. Marine Mammal Science, 35(1), 108–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.12527

Darling, J. D., Keogh, K. E., & Steeves, T. E. (1998). Gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) habitat utilization and prey species off Vancouver Island, B.C. Marine Mammal Science, 14(4), 692–720. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.1998.tb00757.x

Hastie, G. D., Wilson, B., Wilson, L. J., Parsons, K. M., & Thompson, P. M. (2004). Functional mechanisms underlying cetacean distribution patterns: Hotspots for bottlenose dolphins are linked to foraging. Marine Biology, 144(2), 397–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-003-1195-4

Mann, J. (1999). Behavioral sampling methods for cetaceans: A review and critique. Marine Mammal Science, 15(1), 102–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00784.x

Slooten, E. (1994). Behavior of Hector’s Dolphin: Classifying Behavior by Sequence Analysis. Journal of Mammalogy, 75(4), 956–964. https://doi.org/10.2307/1382477

Torres, L. G., Nieukirk, S. L., Lemos, L., & Chandler, T. E. (2018). Drone up! Quantifying whale behavior from a new perspective improves observational capacity. Frontiers in Marine Science, 5(SEP). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00319

Mayo, C. A., & Marx, M. K. (1990). Surface foraging behaviour of the North Atlantic right whale, Eubalaena glacialis, and associated zooplankton characteristics. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 68(10), 2214–2220. https://doi.org/10.1139/z90-308

s on the ecology, behavior and conservation of marine megafauna including cetaceans, pinnipeds, seabirds, and sharks. My research in particular is centered around the cetacean species that inhabit Oregon’s near coastal waters. While the cetacean order includes over 80 species, 30 of which can be found in Oregon, I am specifically targeting the small and charismatic harbor porpoise! I am hoping to answer questions about seasonal and diel patterns, and the drivers of these patterns to create a better understanding of the porpoise community off the coast of Newport.

s on the ecology, behavior and conservation of marine megafauna including cetaceans, pinnipeds, seabirds, and sharks. My research in particular is centered around the cetacean species that inhabit Oregon’s near coastal waters. While the cetacean order includes over 80 species, 30 of which can be found in Oregon, I am specifically targeting the small and charismatic harbor porpoise! I am hoping to answer questions about seasonal and diel patterns, and the drivers of these patterns to create a better understanding of the porpoise community off the coast of Newport.