Clara Bird, Masters Student, OSU Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

The field season can be quite a hectic time of year. Between long days out on the water, trouble-shooting technology issues, organizing/processing the data as it comes in, and keeping up with our other projects/responsibilities, it can be quite overwhelming and exhausting.

But despite all of that, it’s an incredible and exciting time of year. Outside of the field season, we spend most of our time staring at our computers analyzing the data that we spend a relatively short amount of time collecting. When going through that process it can be easy to lose sight of why we do what we do, and to feel disconnected from the species we are studying. Oftentimes the analysis problems we encounter involve more hours of digging through coding discussion boards than learning about the animals themselves. So, as busy as it is, I find that the field season can be pretty inspiring. I have recently been looking through our most recent drone footage of gray whales and feeling renewed excitement for my thesis.

At the moment, my thesis has four central questions: (1) Are there associations between habitat type and gray whale foraging tactic? (2) Is there evidence of individualization? (3) What is the relationship between behavior and body condition? (4) Do we see evidence of learning in the behavior of mom and calf pairs? As I’ve been organizing my thoughts, what’s become quite clear is how interconnected these questions are. So, I thought I’d take this blog to describe the potential relationships.

Let’s start with the first question: are there associations between habitat types and gray whale foraging tactics? This question is central because it relates foraging behavior to habitat, which is ultimately associated with prey. This relationship is the foundation of all other questions involving foraging tactics because food is necessary for the whales to have the energy and nutrients they need to survive. It’s reasonable to think that the whales are flexible and use different foraging tactics to eat different prey that live in different habitats. But, if different prey types have different nutritional value (this is something that Lisa is studying right now; check out the COZI project to learn more), then not all whales may be getting the same nutrients.

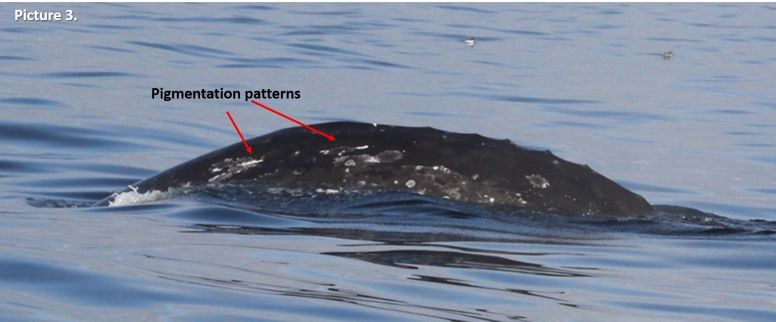

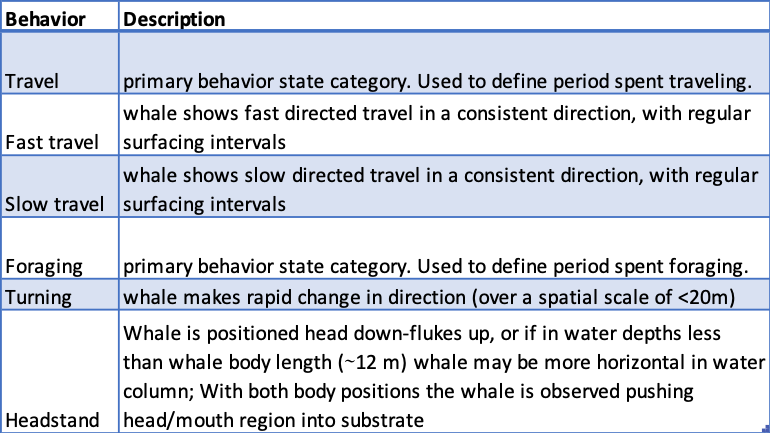

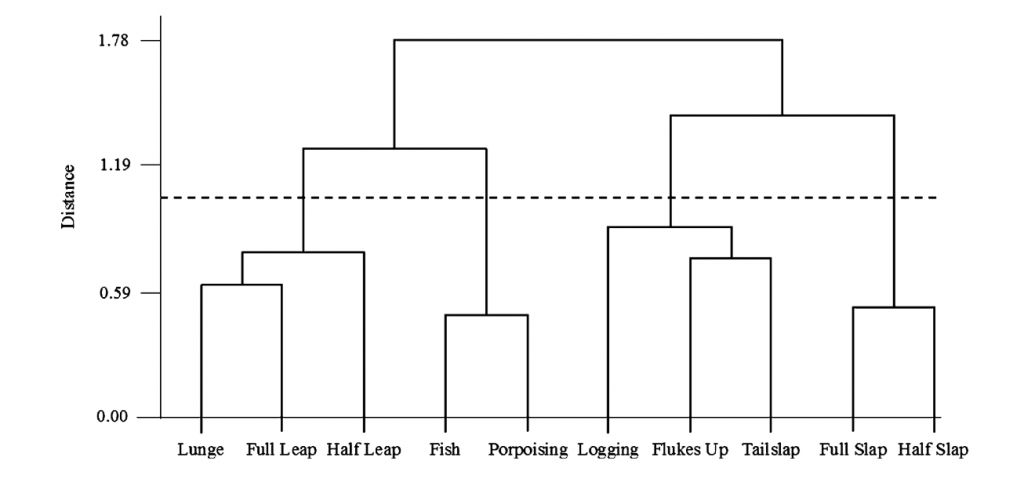

The next question relates to the first question but is not necessarily dependent on it. It’s the question of individualization, a topic Lisa also explored in a past blog. Within our Oregon field sites we have documented a variety of gray whale foraging tactics (Torres et al. 2018; Video 1) but we do not know if all gray whales use all the tactics or if different individuals only use certain tactics. While I think it’s unlikely that one whale only uses one tactic all the time, I think we could see an individual use one tactic more often than the others. I reason that there could be two reasons for this pattern. First, it could be a response to resource availability; certain tactics are more efficient than others, this could be because the tactic involves capturing the more nutritious prey or because the behavior is less energetically demanding. Second, foraging tactics are socially learned as calves from their mothers, and hence individuals use those learned tactics more frequently. This pattern of maternally inherited foraging tactics has been documented in other marine mammals (Mann and Sargeant 2009; Estes et al. 2003). These questions between foraging tactic, habitat and individualization also tie into the remaining two questions.

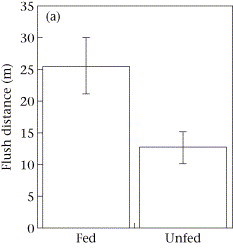

My third question is about the relationship between behavior and body condition. As I’ve discussed in a previous blog, I am interested in assessing the relative energetic costs and benefits of the different foraging tactics. Is one foraging tactic more cost-effective than another (less energy out per energy in)? Ever since our lab’s cetacean behavioral ecology class, I’ve been thinking about how my work relates to niche partitioning theory (Pianka 1974).This theory states that when there is low prey availability, niche partitioning will increase. Niche partitioning can occur across several different dimensions: for instance, prey type, foraging location, and time of day when active. If gray whales partition across the prey type dimension, then different whales would feed on different kinds of prey. If whales partition resources across the foraging location dimension, individuals would feed in different areas. Lastly, if whales partition resources across the time axis, individuals would feed at different times of day. Using different foraging tactics to feed on different prey would be an example of partitioning across the prey type dimension. If there is a more preferable prey type, then maybe in years of high prey availability, we would see most of the gray whales using the same tactics to feed on the same prey type. However, in years of low prey availability we might expect to see a greater variety of foraging tactics being used. The question then becomes, does any whale end up using the less beneficial foraging tactic? If so, which whales use the less beneficial tactic? Do the same individuals always switch to the less beneficial tactic? Is there a common characteristic among the individuals that switched, like sex, age, size, or reproductive status? Lemos et al. (2020) hypothesized that the decline in body condition observed from 2016 to 2017 might be a carryover effect from low prey availability in 2016. Could it be that the whales that use the less beneficial tactic exhibit poor body condition the following year?

My fourth, and final, question asks if foraging tactics are passed down from moms to their calves. We have some footage of a mom foraging with her calf nearby, and occasionally it looks like the calf could be copying its mother. Reviewing this footage spiked my interest in seeing if there are similarities between the behavior tactics used by moms and those used by their calves after they have been weaned. While this question clearly relates to the question of individualization, it is also related to body condition: what if the foraging tactics used by the mom is influenced by her body condition at the time?

I hope to answer some of these fascinating questions using the data we have collected during our long field days over the past 6 years. In all likelihood, the story that comes together during my thesis research will be different from what I envision now and will likely lead to more questions. That being said, I’m excited to see how the story unfolds and I look forward to sharing the evolving ideas and plot lines with all of you.

References

Estes, J A, M L Riedman, M M Staedler, M T Tinker, and B E Lyon. 2003. “Individual Variation in Prey Selection by Sea Otters: Patterns, Causes and Implications.” Source: Journal of Animal Ecology. Vol. 72.

Mann, Janet, and Brooke Sargeant. 2009. “ Like Mother, like Calf: The Ontogeny of Foraging Traditions in Wild Indian Ocean Bottlenose Dolphins ( Tursiops Sp.) .” In The Biology of Traditions, 236–66. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511584022.010.

Pianka, Eric R. 1974. “Niche Overlap and Diffuse Competition” 71 (5): 2141–45.

Soledade Lemos, Leila, Jonathan D Burnett, Todd E Chandler, James L Sumich, and Leigh G. Torres. 2020. “Intra‐ and Inter‐annual Variation in Gray Whale Body Condition on a Foraging Ground.” Ecosphere 11 (4). https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3094.

Torres, Leigh G., Sharon L. Nieukirk, Leila Lemos, and Todd E. Chandler. 2018. “Drone up! Quantifying Whale Behavior from a New Perspective Improves Observational Capacity.” Frontiers in Marine Science 5 (SEP). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00319.