Dr. KC Bierlich, Dr. Alejandro Fernández Ajó, and Dr. Leigh Torres, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, & Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

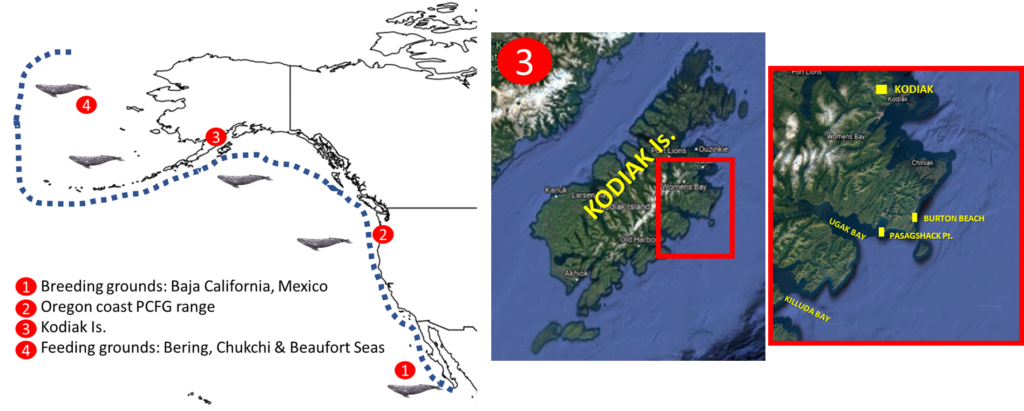

Eastern North Pacific (ENP) gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) undertake one of the longest annual migrations of any mammal, traveling from their winter breeding grounds in the warm waters of Baja California, Mexico to their summer feeding grounds in the icy waters of the Bering and Chukchi Seas1,2. Yet, a distinct subgroup of this population, called the Pacific Coast Feeding Group (PCFG), instead shorten their migration farther south to spend the summer foraging along waters from northern California, USA to northern British Columbia, Canada1 (Figure 1). On these summer feeding grounds gray whales will forage almost continuously to increase their energy reserves to support migration and reproduction during the rest of the year.

The GEMM Lab has been studying the ecology and physiology of the PCFG gray whales in Oregon waters since 2015, combining traditional photo-ID and behavioral observation methods with fecal sample collection, drone flights, and prey assessment to integrate data on individual whale behavior, nutritional status, prey consumption, and hormone variation. These multidisciplinary methods have proven effective to obtain an improved understanding of PCFG gray whale body condition and hormone variation by demographic unit and over time3,4,5, as well as prey energetics and foraging ecology6.

Since the PCFG remains a small proportion (~230 individuals) of the larger eastern ENP population (~20,000 individuals), the GEMM Lab and multiple collaborators are interested in extending the research design implemented by the GEMM Lab in Oregon to study gray whale ecology and physiology of whales feeding on the more northern foraging grounds. The goal would be to fill some of the many critical knowledge gaps including gray whale resilience and response to climate change, connectivity between foraging grounds, population dynamics of the PCFG and ENP, and physiological variation (body condition, hormones) as a function of habitat, prey, demography, and time of year.

Kodiak Island, Alaska is a middle distance between PCFG foraging grounds in Newport, Oregon and the traditional ENP foraging grounds in Chukchi and Beaufort Seas (Figure 1). Two studies documented high gray whale encounter rates in Ugak Bay in Kodiak Island, including during summer months when foraging behavior was observed7,8. Evidence from photo-ID matches in these studies indicated that some PCFG whales might also extends their feeding grounds further north to Kodiak Island7,8.

During August-September of this year, GEMM Lab postdocs KC Bierlich and Alejandro Fernández Ajó traveled to Kodiak Island to assess opportunities for researching gray whales in the area. The mission objectives included determining gray whale presence, assessing behavioral states and foraging areas, determining feasibility of drone operations and fecal sample collection, collecting photo ID images, assessing feasibility of boat and shore-based operations in Ugak Bay (Figure 1), and connecting with local scientists and stakeholders interested in collaborating.

We landed in Kodiak the evening of August 28 (Figure 2), with a beautiful sunset. The next morning, we met our captain, Alexus Kwachka, over breakfast to discuss a plan for going offshore to look for gray whales later in the week. Alexus is a local fisherman in Kodiak with over 30 years of experience fishing in Alaska and incredible knowledge on local wildlife and navigating the rough Alaskan seas. It was particularly interesting to hear his stories on the local changes he has noticed over the years, not just in weather and fishing, but also in the seals, birds, and whales.

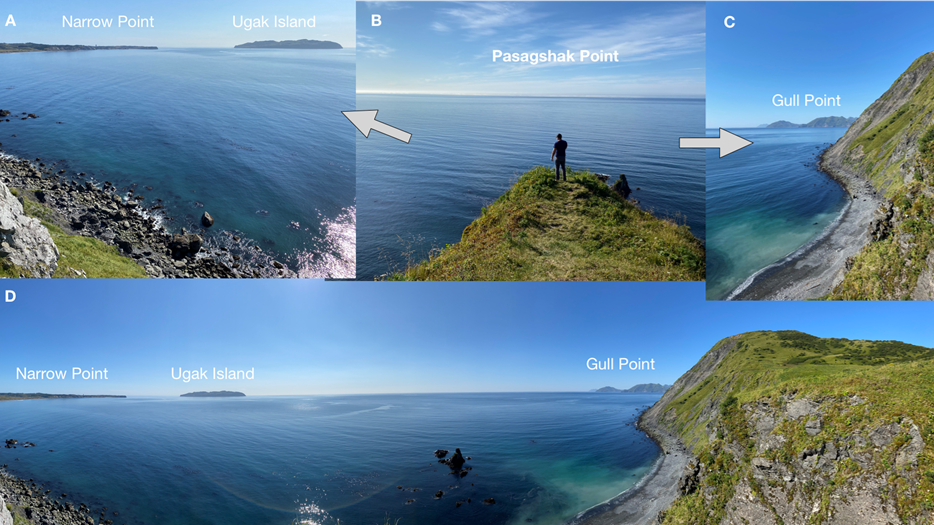

Next, we met with Sun’aq Tribe’s biologist Matthew Van Daele, who coordinates the marine mammal stranding network on Kodiak Island and has a deep knowledge of the locations to find whales. Matt showed us several great spots to scout for gray whales along the shore in the Pasagshak area (Figure 1), which overlooks Ugak Bay and is about 1 hour drive from Kodiak (Figure 3). Along the way, Matt discussed the high mortality rate of gray whales he has observed over the past two years and his concerns about some skinny whales in the area he recently observed during aerial surveys. Since 2019, an Unusual Mortality Event (UME) of gray whales along the whole North Pacific west coast (Mexico, USA, Canada) has impacted the ENP gray whales and while the exact cause(s) of these mortalities is largely unknown, evidence suggests reduced nutritional status may be a likely cause of death9. We learned from Matt that while gray whale strandings are decreasing compared to the previous two years, the numbers are still concerningly high. It was an absolute pleasure spending the day with Matt, as being born and raised in Kodiak he has such great knowledge of the area and the local wildlife. Together we saw Kodiak’s beautiful landscape with lots of different wildlife, which included some huge Kodiak brown bears a few hundred meters away from the road (Figure 4).

The next day, the weather was great, so we returned to the Pasagshak lookout points to spend the day looking for whales. We spotted several gray whales from the cliffs and shore. At Burton Beach, we spotted a gray whale very close to shore that first appeared to be traveling, but then changed direction and started moving closer inshore –less than 10 m from where we were standing on the beach! The whale then swam back and forth along the shore, providing an opportunity to collect photos of its right and left side to use for photo ID. KC flew the drone over the whale and recorded some amazing behavior of lateral swimming and great images for photogrammetry. Our excitement was sky high as within two days on the trip we had documented the presence of gray whales, recorded the best places to work from land, and even captured some interesting behavior, photo ID, and photogrammetry data from shore! (Figure 5).

The weather deteriorated over the next couple days, bringing foggy and rainy conditions. We used this time to process data and meet with some of the local researchers. When the weather conditions improved, we met back up with Alexus and boarded his fishing vessel, “No Point”, and headed off to Ugak Bay to look for gray whales. During transit we encountered a humpback whale mother-calf pair lunge feeding and breaching (Figure 6). As we approached Pasagshak we sighted a gray whale diving and benthic feeding in 60 m water depth, and then 2-3 other individual whales exhibiting the same behavior close by. We collected photo ID data, but high wind conditions hindered drone operations, so we continued surveying further into Ugak Bay and turned around following the coast towards Gull Point (Figure 7).

During our survey effort we spotted a gray whale foraging on a shallow rocky, kelp reef (12 m depth) along the northwest point of Ugak Bay. This sighting was similar to behavior we often observe in Oregon, with whales feeding in near shore shallow, reef habitats. Conditions for flying the drone were still too windy, but we observed the whale defecate and collected a fecal sample! For us, fecal samples are like “biological gold”, as we can study hormones (which include assessments of their reproductive status, nutritional condition, sex determination, and stress levels), genetics, prey, and much more! We were so excited to collect this sample because it provides the chance to start looking at the physiological parameters of these Alaskan whales and compare findings to what we observe in samples collected from whales in Oregon (Figure 8).

After a beautiful night anchored in a sheltered bay near Gull Point (Figure 9) we continued west to scan for whales. Back in Ugak Bay, we found six more gray whales diving and feeding in 50-60 m depth near the same location as the previous day off Pasagshak point. Weather conditions had finally improved, allowing us to fly the drone. We flew over four whales and collected video for behavior and photogrammetry analysis, which allows us to measure the body condition of the whales to assess how healthy it is (Figure 10).

Another highlight of our field work was the collection of a benthic prey sample using a Ponar grab sampler at this location in Pasagshak Bay where the whales were foraging. The bottom was muddy and rich with invertebrates; the sample literally looked like it was boiling from the amount of prey in it (Figure 11). From this sample, we will determine the invertebrate species and caloric content of these prey for comparison to the prey found in Oregon waters.

Overall, this scouting mission to Kodiak was a great success! Through boat surveys, shore-based observations, and the conversations with locals, we determined the best areas and timing to effectively work from boats and shore to expand our gray whale research to Kodiak. Moreover, our scouting mission resulted in the collection of relevant pilot data including fecal samples for hormonal analyses, drone images for body condition and behavioral assessments, prey samples, and photo-ID images. This scouting mission identified several knowledge gaps regarding gray whale ecology, physiology, and population connectivity that can be feasibly addressed through expansion of GEMM Lab research efforts to the Alaskan region. Importantly, the trip facilitated important networking with locals to establish potential collaborations for future work. We are optimistic and excited to grow our collaborative research in Kodiak.

This pilot project was funded by sales and renewals of the special Oregon whale license plate, which benefits MMI. We gratefully thank all the gray whale license plate holders, who made this scouting trip possible.

References:

1 Calambokidis J, Darling JD, Deecke V, Gearin P, Gosho M, Megill W, et al. Abundance, range and movements of a feeding aggregation of gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) from California to south- eastern Alaska in 1998. J Cetacean Res Manag 2002; 4:267–76.

2Stewart JD, Weller DW. Abundance of eastern North Pacific gray whales 2019/2020. 2021. U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SWFSC-639. https://doi.org/10. 25923/bmam-pemorandum NMFS-SWFSC-639. https://doi.org/10. 25923/bmam-pe91.

3Lemos, L. S. et al. Assessment of fecal steroid and thyroid hormone metabolites in eastern North Pacific gray whales. Conserv. Physiol. 8, (2020).

4Lemos, L. S. et al. Stressed and slim or relaxed and chubby? A simultaneous assessment of gray whale body condition and hormone variability. Mar. Mammal Sci. 1–11 (2021). doi:10.1111/mms.12877

5Soledade Lemos, L., Burnett, J. D., Chandler, T. E., Sumich, J. L. & Torres, L. G. Intra‐ and inter‐annual variation in gray whale body condition on a foraging ground. Ecosphere 11, (2020).

6Hildebrand, L., Bernard, K. S. & Torres, L. G. (2021). Do Gray Whales Count Calories? Comparing Energetic Values of Gray Whale Prey Across Two Different Feeding Grounds in the Eastern North Pacific. Frontiers in Marine Science, 8(July), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.683634

7Gosho Merrill, Patrick Gearin, Ryan Jenkinson, Jeff Laake, Lori Mazzuca, David Kubiak, John Calambokidis, Will Megill, Brian Gisborne, Dawn Goley, Christina Tombach, James Darling, V. D. gosho_et_al._2011_-_sc-m11-awmp2.pdf. (2011).

8Moore, S. E., Wynne, K. M., Kinney, J. C. & Grebmeier, J. M. GRAY WHALE OCCURRENCE AND FORAGE SOUTHEAST OF KODIAK, ISLAND, ALASKA. Mar. Mammal Sci. 23, 419–428 (2007).

9Christiansen F, Rodríguez-González F, Martínez-Aguilar S, Urbán J and others (2021) Poor body condition associated with an unusual mortality event in gray whales. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 658:237-252. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13585

[TL1]Add this link here: