Miranda Fowles, GEMM Lab TOPAZ/JASPER Intern, OSU Fisheries and Wildlife Undergraduate

Hello! My name is Miranda Fowles, and I am the OSU intern for the 2025 TOPAZ/JASPER project this summer! I recently earned my bachelor’s degree – almost, I have one more term, but I walked at commencement in June – from Oregon State University in Fisheries, Wildlife and Conservation Sciences and a minor in Spanish. My interest in whales began at a young age during a visit to SeaWorld. While I didn’t enjoy the killer whale shows for their entertainment aspect, this exposure allowed me to see a whale for the first time. From then on, I knew I wanted to contribute to understanding more about these animals, even if I wasn’t always sure how to make that happen. My decision to pursue Fisheries and Wildlife sciences was set from the beginning, however I wondered if there were actually opportunities to study whales.

Last summer, I was a MACO intern and stayed at the Hatfield Marine Science Center where I met last year’s TOPAZ/JASPER REU student, Sophia Kormann, and she raved all about her experience, so I just had to apply for this year’s internship! I remember feeling so nervous for the interview, but Dr. Leigh Torres and Celest Sorrentino’s kindness and inspiration quickly put me to ease. When I found out I was offered the position, I was just more excited than I’d ever been!

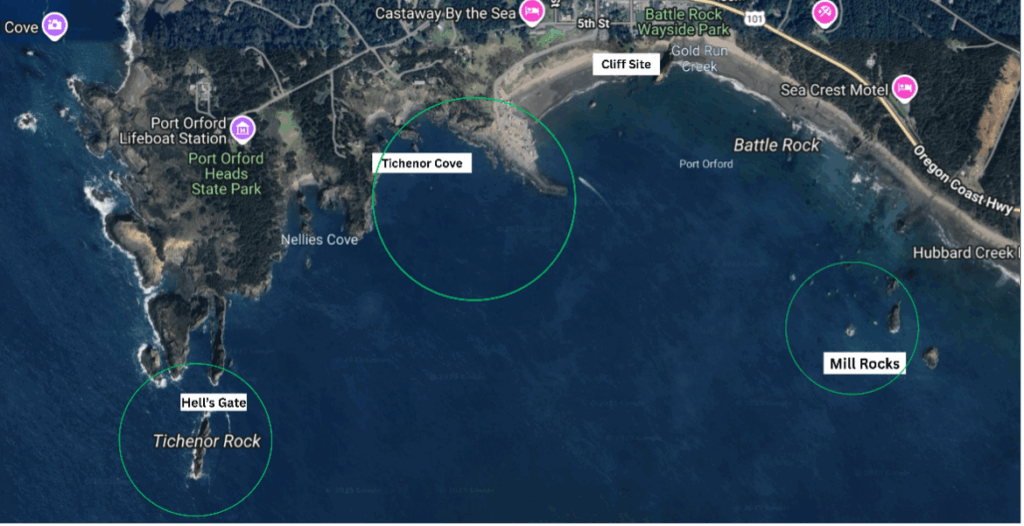

My day-to-day life as a TOPAZ/JASPER intern here at the Port Orford Field Station looks one of two ways: either on the kayak or the cliff site. When we are ocean kayaking, we go to our 12 sampling sites in the Mill Rocks and Tichenor Cove study areas (Fig. 1), where we collect zooplankton samples (Fig. 2) and oceanographic data with our RBR (an oceanographic instrument), as well as GoPro footage. When on the cliff site, we keep our eyes peeled for any whales to take pictures of them and mark their location in the water with a theodolite.

A theodolite is an instrument that is used for mapping and engineering; in our case it is used to track where a gray whale blows and surfaces (For more info, please see this blog by previous intern Jonah Lewis). Each time a whale surfaces, we use the theodolite to create a point in space that marks its location. Once we have multiple points, we can draw lines between each point to establish the track of the whale. These tracklines can then be used to make assumptions of the whales’ behavior. For example, if the trackline is straight, and the individual is moving at a consistent speed and direction, we can assume the whale is transiting. Whereas if the trackline is going back and forth in one small area, the whale is likely searching or foraging for food (Hildebrand et al., 2022).

In last week’s blog my peer Nautika Brown showed how photo ID is a critical part in our field methods. When theodolite tracking, we assign a number with each new individual whale observation. If the whale is close enough, we also capture photographs of the whale (Fig. 3) and match it up to its given number, allowing us to link the trackline to an individual whale so we can understand more about individual behavior. Documenting individual specific behavior is important because previous research has shown that age, size and the individual ID of a whale can all influence different foraging tactic use (Bird et al., 2024). Therefore, each season as we collect more and more data, we establish a repertoire of recurring or new behaviors to sieve for trends and patterns.

I find animal behavior to be an integral role in many ecological studies, and I am intrigued to explore this topic more. As marine mammals that spend most of their time underwater, cetaceans are quite an inconspicuous species to study (Bird et al., 2024), but by studying their ecology through photo ID and theodolite tracking we get insight into who they are, how they behave, and where they go.

Up until this point in the season, we have theodolite tracked gray whales for 12 hours and 3 minutes (woohoo). Interestingly, most of these tracks of whales have been near an area called “Hell’s Gate”, which is located around large rocks toward the far west of our study site (Figs. 2 and 4). We can assume, but cannot be sure, that the whales are feeding here because they spend so much time in the area, and return day after day. According to Dr. Torres, the consistent use of this area near Hell’s Gate by gray whales is unusual. In the prior 10 years of the TOPAZ project, few whales have been tracked foraging in this area near Hell’s Gate, but rather most whales have foraged in the Mill Rocks and Tichenor Cove areas. It is interesting to think about why the whales are behaving differently this year. Maybe this is due to variations in prey availability at these different sites. In recent years, Port Orford has been affected by a surge in purple sea urchin density, which have overgrazed the once prominent kelp forests here. A high urchin density decreases the kelp condition, which then leads to less habitat for zooplankton, creating a decline in prey availability for gray whales (Hildebrand et al., 2024). Upon reflection of my time on the kayak, I have noticed minimal kelp and low zooplankton abundance when conducting our zooplankton drops in our Mill Rocks and Tichenor Cove study sites. Additionally, I have also noticed many purple sea urchins in our GoPro videos. With the effects of this trophic cascade in mind, not observing any gray whales in our traditional study sites is understandable. With these gray whales more commonly seen near Hell’s Gate this year, I am curious to know what prey is attracting them there. Perhaps it is a different type of prey species or one that is high in caloric value than what is in the Mill Rocks and Tichenor Cove areas.

From actively observing whales and learning from my mentor, Celest, I have started to understand that behavior is a critical piece to any form of studying gray whales (and all species). By integrating photo-ID and theodolite tracking, we can learn so much about whale behavior, from where they eat, who is spending time where, and how they may adjust their behavior in response to a changing environment. The TOPAZ/JASPER internship has allowed me to truly comprehend what field research is like, how studying the behaviors of an individual is important, and how detail and patience are extremely necessary when collecting data. As this summer is continuing, I wonder if we will continue to see gray whales primarily feeding in the Hell’s Gate area, or if we will start to observe them more in the Mill Rocks and Tichenor Cove sites like previous years. The thrill of seeing gray whales is unlike any other, and I am so ready to see more whales this season!

References:

Bird, C. N., Pirotta, E., New, L., Bierlich, K. C., Donnelly, M., Hildebrand, L., Fernandez Ajó, A., & Torres, L. G. (2024). Growing into it: Evidence of an ontogenetic shift in grey whale use of foraging tactics. Animal Behaviour, 214, 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2024.06.004

Hildebrand, L., Derville, S., Hildebrand, I., & Torres, L. G. (2024). Exploring indirect effects of a classic trophic cascade between urchins and kelp on zooplankton and whales. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 9815. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59964-x

Hildebrand, L, Sullivan, F. A., Orben, R. A., Derville. S., Torres L. G. (2022) Trade-offs in prey quantity and quality in gray whale foraging. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 695:189-201 https://doi-org.oregonstate.idm.oclc.org/10.3354/meps14115