Clara Bird, PhD Student, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

The start of a new school year is always an exciting time. Like high school, it means seeing friends again and the anticipation of preparing to learn something new. Even now, as a grad student less focused on coursework, the start of the academic year involves setting project timelines and goals, most of which include learning. As I’ve been reflecting on these goals, one of my dad’s favorite sayings has been at the forefront of my mind. As an overachieving and perfectionist kid, I often got caught up in the pursuit of perfect grades, so the phrase “just learn the stuff” was my dad’s reminder to focus on what matters. Getting good grades didn’t matter if I wasn’t learning. While my younger self found the phrase rather frustrating, I have come to appreciate and find comfort in it.

Given that my research is focused on behavioral ecology, I’ve also spent a lot of time thinking about how gray whales learn. Learning is important, but also costly. It involves an investment of energy (a physiological cost, Christie & Schrater, 2015; Jaumann et al., 2013), and an investment of time (an opportunity cost). Understanding the costs and benefits of learning can help inform conservation efforts because how an individual learns today affects the knowledge and tactics that the individual will use in the future.

Like humans, individual animals can learn a variety of tactics in a variety of ways. In behavioral ecology we classify the different types of learning based on the teacher’s role (even though they may not be consciously teaching). For example, vertical transmission is a calf learning from its mom, and horizontal transmission is an individual learning from other conspecifics (individuals of the same species) (Sargeant & Mann, 2009). An individual must be careful when choosing who to learn from because not all strategies will be equally efficient. So, it stands to reason than an individual should choose to learn from a successful individual. Signals of success can include factors such as size and age. An individual’s parent is an example of success because they were able to reproduce (Barrett et al., 2017). Learning in a population can be studied by assessing which individuals are learning, who they are learning from, and which learned behaviors become the most common.

An example of such a study is Barrett et al. (2017) where researchers conducted an experiment on capuchin monkeys in Costa Rica. This study centered around the Panama ́fruit, which is extremely difficult to open and there are several documented capuchin foraging tactics for processing and consuming the fruit (Figure 1). For this study, the researchers worked with a group of monkeys who lived in a habitat where the fruit was not found, but the group included several older members who had learned Panamá fruit foraging tactics prior to joining this group. During a 75-day experiment, the researchers placed fruits near the group (while they weren’t looking) and then recorded the tactics used to process the fruit and who used each tactic. Their results showed that the most efficient tactic became the most common tactic over time, and that age-bias was a contributing factor, meaning that individuals were more like to copy older members of the group.

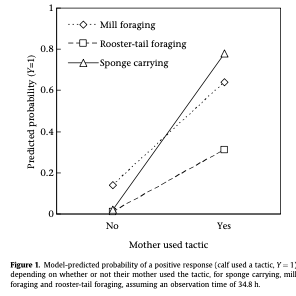

Social learning has also been documented in dolphin societies. A long-term study on wild bottlenose dolphins in Shark Bay, Australia assessed how habitat characteristics and the foraging behaviors used by moms and other conspecifics affected the foraging tactics used by calves (Sargeant & Mann, 2009). Interestingly, although various factors predicted what foraging tactic was used, the dominant factor was vertical transmission where the calf used the tactic learned from its mom (Figure 2). Overall, this study highlights the importance of considering a variety of factors because behavioral diversity and learning are context dependent.

Social learning is something that I am extremely interested in studying in our study population of gray whales in Oregon. While studies on social learning for such long-lived animals require a longer study period than of the span of our current dataset, I still find it important to consider the role learning may play. One day I would love to delve into the different factors of learning by these gray whales and answer questions such as those addressed in the studies I described above. Which foraging tactics are learned? How much of a factor is vertical transmission? Considering that gray whale calves spend the first few months of the foraging season with their mothers I would expect that there is at least some degree of vertical transmission present. Furthermore, how do environmental conditions affect learning? What tactics are learned in good vs. poor years of prey availability? Does it matter which tactic is learned first? While the chances that I’ll get to address these questions in the next few years are low, I do think that investigating how tactic diversity changes across age groups could be a good place to start. As I’ve discussed in a previous blog, my first dissertation chapter will focus on quantifying the degree of individual specialization present in my study group. After reading about age-biased learning, I am curious to see if older whales, as a group, use fewer tactics and if those tactics are the most energetically efficient.

The importance of understanding learning is related to that of studying individual specialization, which can allows us to estimate how behavioral tactics might change in popularity over time and space. We could then combine this with knowledge of how tactics are related to morphology and habitat and the associated energetic costs of each tactic. This knowledge would allow us to estimate the impacts of environmental change on individuals and the population. While my dissertation research only aims to provide a few puzzle pieces in this very large and complicated gray whale ecology puzzle, I am excited to see what I find. Writing this blog has both inspired new questions and served as a good reminder to be more patient with myself because I am still, “just learning the stuff”.