By Mateo Estrada Jorge, Oregon State University undergraduate student, GEMM Lab REU Intern

Introduction

My name is Mateo Estrada and this past summer I had the pleasure of working with Dawn Barlow and Dr. Leigh Torres as a National Science Foundation (NSF) Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) intern. I had the chance to proactively learn about the scientific method in the marine sciences by studying the acoustic behaviors of pygmy blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus brevicauda) that are documented residents of the South Taranaki Bight region in New Zealand (Torres 2013, Barlow et al. 2018). I’ve been interested in conducting scientific research since I began my undergraduate education at Oregon State University in 2015. Having the opportunity to apply the skills I gained through my education in this REU has been a blessing. I’m a physics and computer science major, but more than anything I’m a scientist and my passion has taken me in new, unexpected directions that I’m going to share in this blog post. My message for any students who feel like they haven’t found their path yet is: hang in there, sometimes it takes time for things to take shape. That has been my experience and I’m sure it’s been the experience of many people interested in the sciences. I’m a Physics and Computer Science student, so why am I studying blue whales, and more specifically, how can I be doing marine science research having only taken intro to biology 101?

My background

I decided to apply for the REU in the Spring 2021 because it was a chance to use my programming skills in the marine sciences. I’m also passionate about conservation and protecting the environment in a pragmatic way, so I decided to find a niche where I could put my technical skills to good use. Finally, I wanted to explore a scientific field outside of my area of expertise to grow as a student and to learn from other researchers. I was mostly inspired by anecdotal tales of Physicist Richard Feynman who would venture out of the physics department at Caltech and into other departments to learn about what other scientists were investigating to inspire his own work. This summer, I ventured into the world of marine science, and what I found in my project was fascinating.

Whale watching tour

To get into the research mode, I decided to go on a whale watching tour with the Aquarium of the Pacific. The tour was two hours long and the sunburn was worth it because we got to see four blue whales off the Long Beach coast in California. I got to see the famous blue whale blow and their splashes. It was the first time I was on a big boat in the ocean, so naturally I got seasick (Fig 1). But it was exciting to get a chance to see blue whales in action (luckily, I didn’t actually hurl). The marine biologist onboard also gave a quick lecture on the relative size of blue whales and some of their behaviors. She also pointed out that they don’t use Sonar to locate whales as this has been shown to disturb their calling behaviors. Instead, we looked for a blow and splashing. The tour was a wonderful experience and I’m glad I got to see some whales out in nature. This experience also served as a reminder of the beauty of marine life and the responsibility I feel for trying to understand and help conserving it.

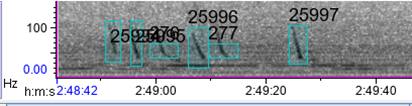

Context of blue whale calling

Sound plays a significant role in the marine environment and is a critical mode of communication for many marine animals including baleen whales. Blue whales produce different vocalizations, otherwise known as calls. Blue whale song is theorized to be produced by males of the species as a form of reproductive behavior, similar to how male peacocks engage females by displaying their elongated upper tail covert feathers in iridescent colors as a courtship mechanism. Then there are “D calls” that are associated with social mechanisms while foraging, and these calls are made by both female and male blue whales (Lewis et al. 2018) (Fig. 2).

Understanding research on blue whales

The most difficult part about coming into a project as an outsider is catching up. I learned how anthropogenetic (human made) noise affects blue whale communication. For example, it has been showing that Mid Frequency Active Sonar signals employed by the U.S. Navy affect blue whale D calling patterns (Melcón 2012). Furthermore, noise from seismic airguns used for oil and gas exploration has also impact blue whale calling behavior (Di Lorio, 2010). Understanding the environmental context in which the pygmy blue whales live and the anthropogenic pressures they face is essential in marine conservation. Protecting the areas in which they live is important so they can feed, reproduce and thrive effectively. What began as a slowly falling snowflake at the start of a snowstorm turned into a cascading avalanche of knowledge pouring into my mind in just two weeks.

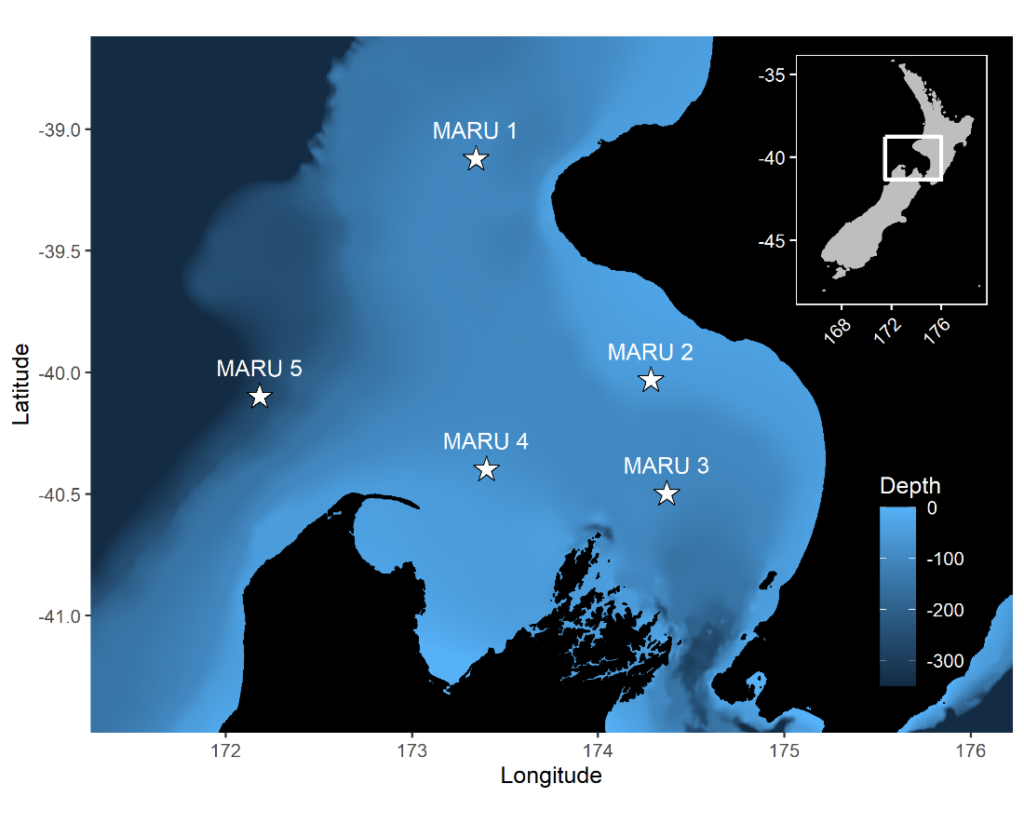

The research question I set out to tackle in my internship was: do blue whales change their calling behavior in response to natural noise events from earthquake activity? To do this, I used acoustic recordings from five hydrophones deployed in the South Taranaki Bight (Fig. 3), paired with an existing dataset of all recorded earthquakes in New Zealand (GeoNet). I identified known earthquakes in our acoustic recordings, and then examined the blue whale D calls during 4 hours before and after each earthquake event to look for any change in the number of calls, call energy, entropy, or bandwidth.

A great mentor and lab team

The days kept passing and blending into each other, as they often do with remote work. I began to feel isolated from the people I was working with and the blue whales I was studying. The zoom calls, group chats, and working alongside other remote interns kept me afloat as I adapted to a work world fully online. Nevertheless, I was happy to continue working on this project because I felt like I was slowly becoming part of the GEMM Lab. I would meet with my mentor Dawn Barlow at least once a week and we would spend time talking about the project and sorting out the difficult details of data processing. She always encouraged my curiosity to ask questions. Even if they were silly questions, she was happy to ponder them because she is a curious scientist like myself.

What we learned

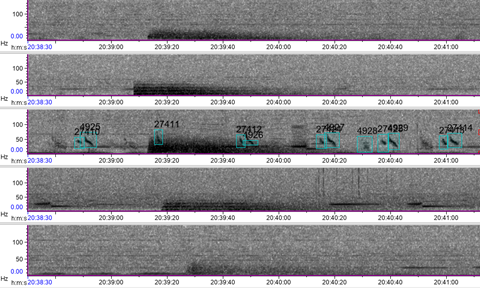

Pygmy blue whales from the South Taranaki Bight region do not change their acoustic behavior in response to earthquake activity. The energy of the earthquake, magnitude, depth, and distance to the origin all had no influence on the number of blue whale D calls, the energy of their calling, the entropy, and the bandwidth. A likely reason for why the blue whales would have no acoustic response to earthquakes (magnitude < 5) is that the STB region is a seismically active region due to the nearby interface of the Australian and Pacific plates. Because of the plate tectonics, the region averages about 20,000 recorded earthquakes per year (GeoNet: Earthquake Statistics). Given that pygmy blue whales are present in the STB region year-round (Barlow et al. 2018), the blue whales may have adapted to tolerate the earthquake activity (Fig 4).

Looking at the future

I presented my work at the end of my REU internship program, which was a difficult challenge for me because I am often intimidated by public speaking (who isn’t?). Communicating science has always been a big interest of me. I love reading news articles about new breakthroughs and being a small part of that is a huge privilege for me. Finding my own voice and having new insights to contribute to the scientific world has always been my main objective. Now I will get to deliver a poster presentation of my REU work at the Association for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography (ASLO) Conference in March 2022. I am both excited and nervous to take on this new adventure of meeting seasoned professionals, communicating my results, and learning about the ocean sciences. I hope to gain new inspirations for my future academic and professional work.

References:

About Earthquake Drums – GeoNet. geonet.Org. Retrieved June 23, 2021, from https://www.geonet.org.nz/about/earthquake/drums

Barlow, D. R., Torres, L. G., Hodge, K. B., Steel, D., Scott Baker, C., Chandler, T. E., Bott, N., Constantine, R., Double, M. C., Gill, P., Glasgow, D., Hamner, R. M., Lilley, C., Ogle, M., Olson, P. A., Peters, C., Stockin, K. A., Tessaglia-Hymes, C. T., & Klinck, H. (2018). Documentation of a New Zealand blue whale population based on multiple lines of evidence. Endangered Species Research, 36, 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00891

Di Iorio, L., & Clark, C. W. (2010). Exposure to seismic survey alters blue whale acoustic communication. Biology Letters, 6(3), 334–335. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2009.0967

Lewis, L. A., Calambokidis, J., Stimpert, A. K., Fahlbusch, J., Friedlaender, A. S., McKenna, M. F., Mesnick, S. L., Oleson, E. M., Southall, B. L., Szesciorka, A. R., & Sirović, A. (2018). Context-dependent variability in blue whale acoustic behaviour. Royal Society Open Science, 5(8). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.180241

Melcón, M. L., Cummins, A. J., Kerosky, S. M., Roche, L. K., Wiggins, S. M., & Hildebrand, J. A. (2012). Blue whales respond to anthropogenic noise. PLoS ONE, 7(2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0032681

Torres LG. 2013 Evidence for an unrecognised blue whale foraging ground in New Zealand. NZ J. Mar. Freshwater Res. 47, 235–248. (doi:10. 1080/00288330.2013.773919)