By Leila S. Lemos, Ph.D., Postdoctoral Associate at Florida International University, former member of the GEMM Lab (Defended PhD. March 2020)

It’s been a long time since I wrote a blog post for the GEMM Lab (more than two years ago!). You may remember me as a former Ph.D. student working with gray whale body condition and hormone variation in association with ambient noise… and so much has happened since then!

After my graduation, since I have tropical blood running in my veins, I literally crossed the entire country in search of blue and sunny skies, warm weather and ocean, and of course different opportunities to continue doing research involving stressors and physiological responses in marine mammals and other marine organisms. It didn’t take me long to start a position as a postdoctoral associate with the Institute of Environment at Florida International University. I have learned so much in these past two years while mainly working with toxicology and stress biomarkers in a wide range of marine individuals including corals, oysters, fish, dolphins, and now manatees. I have started a new chapter in my life, and I am very eager to see where it takes me.

Talking about chapters… my Ph.D. thesis comprised four different chapters and I had published only the first one when I left Oregon: “Intra- and inter-annual variation in gray whale body condition on a foraging ground”. In this study we used drone-based photogrammetry to measure and compare gray whale body condition along the Oregon coast over three consecutive foraging seasons (June to October, 2016-2018). We described variations across the different demographic units, improved body condition with the progression of feeding seasons, and variations across years, with a better condition in 2016 compared to the following two years. Then in 2020, I was able to publish my second chapter entitled “Assessment of fecal steroid and thyroid hormone metabolites in eastern North Pacific gray whales”. In this study, we used gray whale fecal samples to validate and quantify four different hormone metabolite concentrations (progestins, androgens, glucocorticoids, and thyroid hormone). We reported variation in progestins and androgens by demographic unit and by year. Almost a year later, my third chapter “Stressed and slim or relaxed and chubby? A simultaneous assessment of gray whale body condition and hormone variability” was published. In this chapter, we documented a negative correlation between body condition and glucocorticoids, meaning that slim whales were more stressed than the chubby ones.

These three chapters were “relatively easy” to publish compared to my fourth chapter, which had a long and somewhat stressful process (which is funny as I am trying to report stress responses in gray whales). Changes between journals, titles, analyses, content, and focus had to be made over the past year and a half for it to be accepted for publication. However, I believe that it was worth the extra work and invested time as our research definitely became more robust after all of the feedback provided by the reviewers. This chapter, now entitled “Effects of vessel traffic and ocean noise on gray whale stress hormones” was finally published earlier this month at the Nature Scientific Reports journal, and I’ll describe it further below.

Increased human activities in the last decades have altered the marine ecosystem, leaving us with a noisier, warmer, and more contaminated ocean. The noise caused by the dramatic increase in commercial and recreational shipping and vessel traffic1-3 has been associated with negative impacts on marine wildlife populations4,5. This is especially true for baleen whales, whose frequencies primarily used for communication, navigation, and foraging6,7 are “masked” by the noise generated by this watercraft. Several studies have reported alterations in marine mammal behavioral states8-11, increased group cohesion12-14, and displacement8,15 due to this disturbance, however, just a few studies have considered their physiological responses. Examples of physiological responses reported in marine mammals include altered metabolic rate15,16 and variations in stress-related hormone (i.e., glucocorticoids) concentrations relative to vessel abundance and ambient noise17,18. Based on this context and on the scarcity of such assessments, we attempted to determine the effects of vessel traffic and associated ambient noise, as well as potential confounding variables (i.e., body condition, age, sex, time), on gray whale fecal glucocorticoid concentrations.

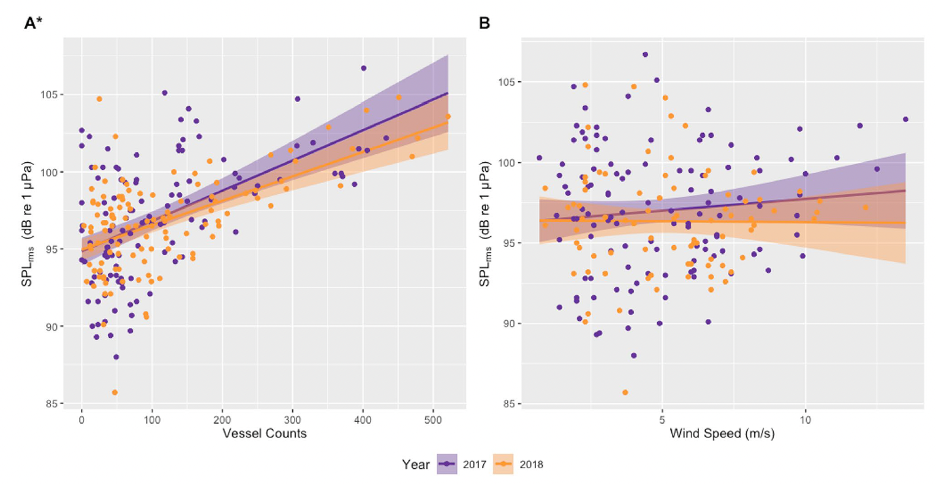

In addition to the data used in my previous three chapters collected from gray whales foraging off the Oregon coast, we also collected ambient noise levels using hydrophones, vessel count data from the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW), and wind data from NOAA National Data Buoy Center (NDBC). Our first finding was a positive correlation between vessel counts and underwater noise levels (Fig. 1A), likely indicating that vessel traffic is the dominant source of noise in the area. To confirm this, we also compared underwater noise levels with wind speed (Fig. 1B), but no correlations were found.

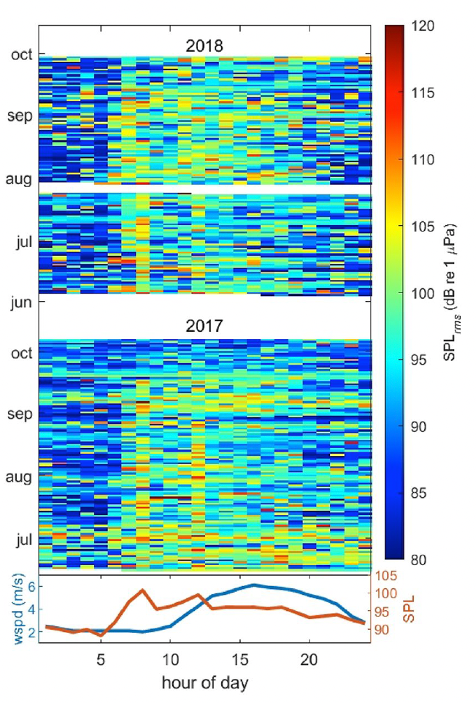

We also investigated noise levels by the hour of the day (Fig. 2), and we found that noise levels peaked between 6 and 8 am most days, coinciding with the peak of vessels leaving the harbor to get to fishing grounds. Another smaller peak is seen at 12 pm, which may represent “half-day fishing charter” vessels returning to the harbor. In contrast, wind speeds (in the lower graph) peaked between 3 and 4 pm, thus confirming the absence of correlation between noise and wind and providing more evidence that noise levels are dominated by the vessel activity in the area.

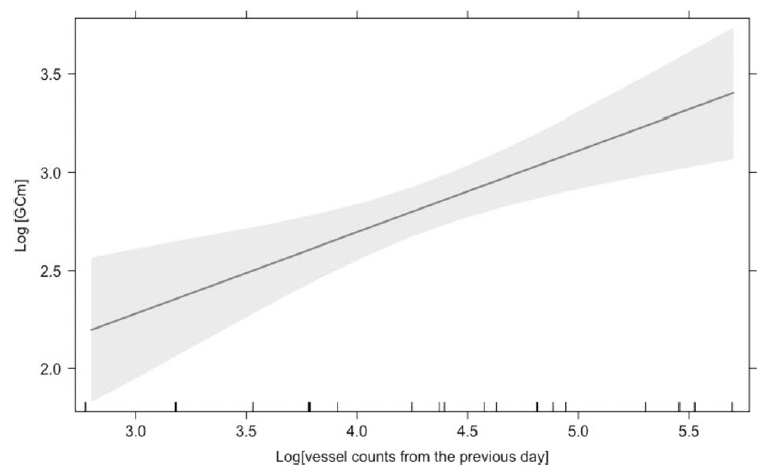

Finally, we assessed the effects of vessel counts, month, year, sex, whale body condition, and other hormone metabolites on glucocorticoid metabolite (GCm; “stress”) concentrations. Since we are working with fecal samples, we needed to consider the whale gut transit time and go back in time to link time of exposure (vessel counts) to response (glucocorticoid concentrations). However, due to uncertainty regarding gut transit time in baleen whales, we compared different time lags between vessel counts and fecal collection. The gut transit time in large mammals is ~12 hours to 4 days3,19,20, so we investigated the influence of vessel counts on whale “stress hormone levels” from the previous 1 to 7 days. The model with the most influential temporal scale included vessel counts from previous day, which showed a significant positive relationship with GCm (the “stress hormone level”) (Fig. 3).

Thus, the “take home messages” of our study are:

- The soundscape in our study area is dominated by vessel noise.

- Vessel counts are strongly correlated with ambient noise levels in our study area.

- Gray whale glucocorticoid levels are positively correlated with vessel counts from previous day meaning that gray whale gut transit time may occur within ~ 24 hours of the disturbance event.

These four chapters were all very important studies not only to advance the knowledge of gray whale and overall baleen whale physiology (as this group is one of the most poorly understood of all mammals given the difficulties in sample collection21), but also to investigate potential sources for the unusual mortality event that is currently happening (2019-present) to the Eastern North Pacific population of gray whales. Such studies can be used to guide future research and to inform population management and conservation efforts regarding minimizing the impact of anthropogenic stressors on whales.

I am very glad to be part of this project, to see such great fruits from our gray whale research, and to know that this project is still at full steam. The GEMM Lab continues to collect and analyze data for determining gray whale body condition and physiological responses in association with ambient noise (Granite, Amber and Diamond projects). The gray whales thank you for this!

Cited Literature

1. McDonald, M. A., Hildebrand, J. A. & Wiggins, S. M. Increases in deep ocean ambient noise in the Northeast Pacific west of San Nicolas Island, California. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 120, 711–718 (2006).

2. Kaplan, M. B. & Solomon, S. A coming boom in commercial shipping? The potential for rapid growth of noise from commercial ships by 2030. Mar. Policy 73, 119–121 (2016).

3. McCarthy, E. International regulation of underwater sound: establishing rules and standards to address ocean noise pollution (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2004).

4. Weilgart, L. S. The impacts of anthropogenic ocean noise on cetaceans and implications for management. Can. J. Zool. 85, 1091–1116 (2007).

5. Bas, A. A. et al. Marine vessels alter the behaviour of bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus in the Istanbul Strait, Turkey. Endanger. Species Res. 34, 1–14 (2017).

6. Erbe, C., Reichmuth, C., Cunningham, K., Lucke, K. & Dooling, R. Communication masking in marine mammals: a review and research strategy. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 103, 15–38 (2016).

7. Erbe, C. et al. The effects of ship noise on marine mammals: a review. Front. Mar. Sci. 6 (2019).

8. Sullivan, F. A. & Torres, L. G. Assessment of vessel disturbance to gray whales to inform sustainable ecotourism. J. Wildl. Manag. 82, 896–905 (2018).

9. Pirotta, E., Merchant, N. D., Thompson, P. M., Barton, T. R. & Lusseau, D. Quantifying the effect of boat disturbance on bottlenose dolphin foraging activity. Biol. Conserv. 181, 82–89 (2015).

10. Dans, S. L., Degrati, M., Pedraza, S. N. & Crespo, E. A. Effects of tour boats on dolphin activity examined with sensitivity analysis of Markov chains. Conserv. Biol. 26, 708–716 (2012).

11. Christiansen, F., Rasmussen, M. & Lusseau, D. Whale watching disrupts feeding activities of minke whales on a feeding ground. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 478, 239–251 (2013).

12. Bejder, L., Samuels, A., Whitehead, H. & Gales, N. Interpreting short-term behavioural responses to disturbance within a longitudinal perspective. Anim. Behav. 72, 1149–1158 (2006).

13. Nowacek, S. M., Wells, R. S. & Solow, A. R. Short-term effects of boat traffic on Bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops truncatus, in Sarasota Bay, Florida. Mar. Mammal. Sci. 17, 673–688 (2001).

14. Bejder, L., Dawson, S. M. & Harraway, J. A. Responses by Hector’s dolphins to boats and swimmers in Porpoise Bay, New Zealand. Mar. Mammal Sci. 15, 738–750 (1999).

15. Lusseau, D. Male and female bottlenose dolphins Tursiops spp. have different strategies to avoid interactions with tour boats in Doubtful Sound. New Zealand. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 257, 267–274 (2003).

16. Sprogis, K. R., Videsen, S. & Madsen, P. T. Vessel noise levels drive behavioural responses of humpback whales with implications for whale-watching. Elife 9, e56760 (2020).

17. Ayres, K. L. et al. Distinguishing the impacts of inadequate prey and vessel traffic on an endangered killer whale (Orcinus orca) population. PLoS ONE 7, e36842 (2012).

18. Rolland, R. M. et al. Evidence that ship noise increases stress in right whales. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 279, 2363–2368 (2012).

19. Wasser, S. K. et al. A generalized fecal glucocorticoid assay for use in a diverse array of nondomestic mammalian and avian species. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 120, 260–275 (2000).

20. Hunt, K. E., Trites, A. W. & Wasser, S. K. Validation of a fecal glucocorticoid assay for Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus). Physiol. Behav. 80, 595–601 (2004).

21. Hunt, K. E. et al. Overcoming the challenges of studying conservation physiology in large whales: a review of available methods. Conserv. Physiol. 1, cot006–cot006 (2013).