Allison Dawn, GEMM Lab Master’s student, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

As the first term of my master’s program comes to an end and we head toward winter break, I am excited by the course material that has already helped direct my research and development as a scientist. There have been new, challenging topics to tackle, and each assignment has fostered deeper thinking into the formation of my thesis. While I learned new methods and analysis approaches this term, a single phrase pervades throughout my studies of ecology – “it depends!”. Ecologists work to uncover patterns driven by natural processes, and this single phrase seems to answer many questions about whether the pattern always exists. A reasonable follow up to that frequently used phrase is, “depends on what?” or “when or where would this pattern change?” In the context of foraging ecology, predator-prey patterns are frequently driven by environmental processes that depend on the scale you choose for your study.

What do we mean by scale? Simply stated, scale is a graduation from one level of measurement to another. You can imagine a ruler, for example. You can measure how tall you are in inches with a ruler or in yards with a yard stick. When we think about scale in ecology, the “ruler” can have traditional units of space (meters, kilometers, etc.), units of time (minutes, days, hours, months, years, etc.), or sometimes both!

The ocean is dynamic and heterogeneous, which simply means there is a lot going on at once. Oceanographic processes influence predator-prey interactions but due to the inherent variability in the system, it is important to explore which factors drive processes that influence patterns at different spatial and temporal scales.

In marine ecology, the “explanatory power” of a factors’ influence on a given process depends on which scale you choose to build your research upon. Ocean ecosystems are hierarchical, with patterns happening at many temporal and spatial scales all at once. So, we could choose to study the same predator-prey interactions at the scale of meters and minutes or 100s of km and months, and we would likely find very different drivers of patterns. The topic of scale is particularly relevant in regard to whale foraging, as marine mammals employ different sensory methods to locate prey at different spatial scales (Torres 2017).

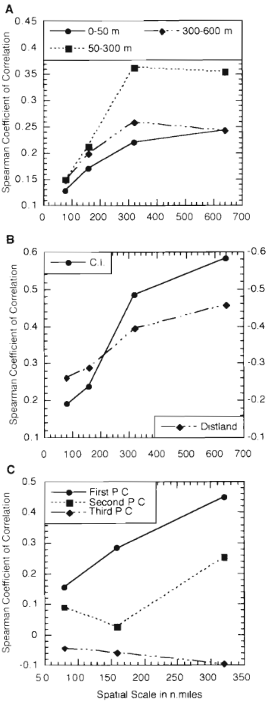

Among the first papers to conduct multi-scale research on whale foraging was Jaquet and Whitehead, 1996. Here, they studied sperm whale distribution in relation to various physical and environmental variables. Analysis showed that the main drivers of sperm whale distribution were secondary productivity (e.g., bacteria and zooplankton), underwater topography, and the gradient between deep water and surface water productivity. However, these drivers had a different impact depending on the spatial scale. There was no correlation between the drivers and sperm whale distribution at small scales < 320 nautical miles. However, at large scales >= 320 nautical miles, female sperm whale distribution was correlated with high secondary productivity and steep underwater topography. These important findings demonstrate that small scale distribution of prey alone does not drive the distribution of sperm whale predators in this study region, while other factors contribute to predator movement.

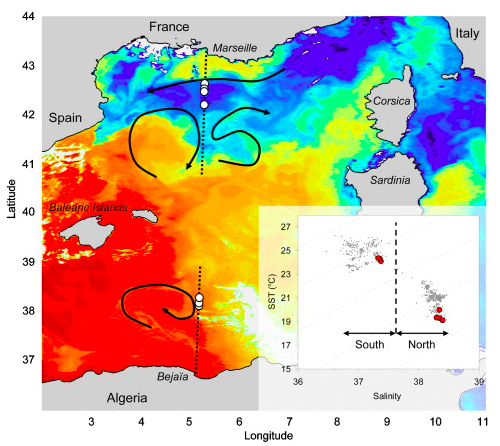

Ten years later, a study on Mediterranean fin whales tackled a similar question of how interactions between prey and predator change at multiple scales. However, their work investigated responses to both spatial and temporal scale changes. Through spatial modeling relative to oceanographic factors, Cotté et al. 2009 found that at a large-scale (year and ocean basin-wide), fin whales demonstrated two distinct distribution patterns: in the summer they were aggregated, and in the winter they were more dispersed. However, at the meso-scale (weeks -months, and 20-100 km) fin whale fidelity switched to colder, saltier waters with steeper topography and temperature gradients. Based on these results, the authors concluded that at the large scale, whale movement was driven by annually persistent prey abundance. At smaller scales, prey aggregations are less predictable, thus the authors suggest that whale movement at the meso-scale is driven by physical processes, such as frontal zones and strong currents.

A key takeaway from these papers is that it is important to investigate how processes and responses can vary at different scales, because results can sometimes depend on the time and space measurement applied in the analysis. For my thesis, I will explore which drivers take a front seat role in gray whale foraging at both fine and meso-scales. I am interested to compare my results on the relationships between PCFG gray whales and their zooplankton prey to the results from the above described studies. Stay tuned for more updates!

Did you enjoy this blog? Want to learn more about marine life, research, and conservation? Subscribe to our blog and get weekly updates and more! Just add your name into the subscribe box on the left panel.

References:

Cotté, C., Guinet, C., Taupier-Letage, I., Mate, B., & Petiau, E. (2009). Scale-dependent habitat use by a large free-ranging predator, the Mediterranean fin whale. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 56(5), 801-811.

Jaquet, N., & Whitehead, H. (1996). Scale-dependent correlation of sperm whale distribution with environmental features and productivity in the South Pacific. Marine ecology progress series, 135, 1-9.

Torres, L. G. (2017). A sense of scale: Foraging cetaceans’ use of scale‐dependent multimodal sensory systems. Marine Mammal Science, 33(4), 1170-1193.