By Lisa Hildebrand, PhD student, OSU Department of Fisheries & Wildlife, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

We are almost halfway through June which means summer has arrived! Although, here on the Oregon coast, it does not entirely feel like it. We have been swinging between hot, sunny days and cloudy, foggy, rainy days that are reminiscent of those in spring or even winter. Despite these weather pendulums, the GEMM Lab’s GRANITE project is off to a great start in its 8th field season! The field team has already ventured out onto the Pacific Ocean in our trusty RHIB Ruby on four separate days looking for gray whales and in this blog post, I am going to share what we have seen so far.

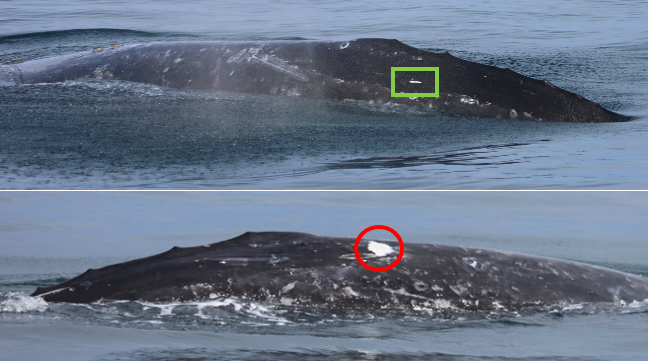

PI Leigh, PhD candidate Clara and I headed out for a “trial run” on May 24th. While the intention for the day was to make sure all our gear was running smoothly and we still remembered how to complete the many tasks associated with our field work (boat loading and trailering, drone flying and catching, poop scooping, data download, to name a few), we could not resist surveying our entire study range given the excellent conditions. It was a day that all marine field scientists hope for – low winds (< 5 kt all day) and a 3 ft swell over a long period. Despite surveying between Waldport and Depoe Bay, we only encountered one whale, but it was a whale that put a smile on each of our faces. After “just” 252 days, we reunited with Solé, the star of our GRANITE dataset, with record numbers of fecal samples and drone flights collected. This record is due to what seems to be a strong habitat or foraging tactic preference by Solé to remain in a relatively small spatial area off the Oregon coast for most of the summer, rather than traveling great swaths of the coast in search for food. Honest truth, on May 24th we found her exactly where we expected to find her. While we did not collect a fecal sample from her on that day, we did perform a drone flight, allowing us to collect a critical early feeding season data point on body condition. We hope that Solé has a summer full of mysids on the Oregon coast and that we will be seeing her often, getting rounder each time!

Just a week after this trial day, we had our official start to the field season with back-to-back days on the water. On our first day, postdoc Alejandro, Clara and I were joined by St. Andrews University Research Fellow Enrico Pirotta, who is another member of the GRANITE team. Enrico’s role in the GRANITE project is to implement our long-term, replicate dataset into a framework called Population consequences of disturbance (PCoD; you can read all about it in a previous blog). We were thrilled that Enrico was able to join us on the water to get a sense for the species and system that he has spent the last several months trying to understand and model quantitatively from a computer halfway across the world. Luckily, the whales sure showed up for Enrico, as we saw a total of seven whales, all of which were known individuals to us! Several of the whales were feeding in water about 20 m deep and surfacing quite erratically, making it hard to get photos of them at times. Our on-board fish finder suggested that there was a mid-water column prey layer that was between 5-7 m thick. Given the flat, sandy substrate the whales were in, we predicted that these layers were composed of porcelain crab larvae. Luckily, we were able to confirm our hypothesis immediately by dropping a zooplankton net to collect a sample of many porcelain crab larvae. Porcelain crab larvae have some of the lowest caloric values of the nearshore zooplankton species that gray whales likely feed on (Hildebrand et al. 2021). Yet, the density of larvae in these thick layers probably made them a very profitable meal, which is likely the reason that we saw another five whales the next day feeding on porcelain crab larvae once again.

On our most recent field work day, we only encountered Solé, suggesting that the porcelain crab swarms had dissipated (or had been excessively munched on by gray whales), and many whales went in search for food elsewhere. We have done a number of zooplankton net tows across our study area and while we did collect a good amount of mysid shrimp already, they were all relatively small. My prediction is that once these mysids grow to a more profitable size in a few days or weeks, we will start seeing more whales again.

So far we have seen nine unique individuals, flown the drone over eight of them, collected fecal samples from five individuals, conducted 10 zooplankton net tows and seven GoPro drops in just four days of field work! We are certainly off to a strong start and we are excited to continue collecting rock solid GRANITE data this summer to continue our efforts to understand gray whale ecology and physiology.

Literature cited

Hildebrand L, Bernard KS, Torres LGT. 2021. Do gray whales count calories? Comparing energetic values of gray whale prey across two different feeding grounds in the Eastern North Pacific. Frontiers in Marine Science 8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.683634