Clara Bird, Masters Student, OSU Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

Imagine that you are a wild foraging animal: In order to forage enough food to survive and be healthy you need to be healthy enough to move around to find and eat your food. Do you see the paradox? You need to be in good condition to forage, and you need to forage to be in good condition. This complex relationship between body condition and behavior is a central aspect of my thesis.

One of the great benefits of having drone data is that we can simultaneously collect data on the body condition of the whale and on its behavior. The GEMM lab has been measuring and monitoring the body condition of gray whales for several years (check out Leila’s blog on photogrammetry for a refresher on her research). However, there is not much research linking the body condition of whales to their behavior. Hence, I have expanded my background research beyond the marine world to looked for papers that tried to understand this connection between the two factors in non-cetaceans. The literature shows that there are examples of both, so let’s go through some case studies.

Ransom et al. (2010) studied the effect of a specific type of contraception on the behavior of a population of feral horses using a mixed model. Aside from looking at the effect of the treatment (a type of contraception), they also considered the effect of body condition. There was no difference in body condition between the treatment and control groups, however, they found that body condition was a strong predictor of feeding, resting, maintenance, and social behaviors. Females with better body condition spent less time foraging than females with poorer body condition. While it was not the main question of the study, these results provide a great example of taking into account the relationship between body condition and behavior when researching any disturbance effect.

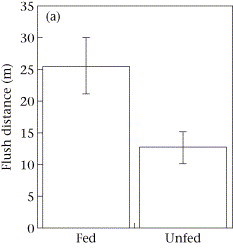

While Ransom et al. (2010) did not find that body condition affected response to treatment, Beale and Monaghan (2004) found that body condition affected the response of seabirds to human disturbance. They altered the body condition of birds at different sites by providing extra food for several days leading up to a standardized disturbance. Then the authors recorded a set of response variables to a disturbance event, such as flush distance (the distance from the disturbance when the birds leave their location). Interestingly, they found that birds with better body condition responded earlier to the disturbance (i.e., when the disturbance was farther away) than birds with poorer body condition (Figure 1). The authors suggest that this was because individuals with better body condition could afford to respond sooner to a disturbance, while individuals with poorer body condition could not afford to stop foraging and move away, and therefore did not show a behavioral response. I emphasize behavioral response because it would have been interesting to monitor the vital rates of the birds during the experiment; maybe the birds’ heart rates increased even though they did not move away. This finding is important when evaluating disturbance effects and management approaches because it demonstrates the importance of considering body condition when evaluating impacts: animals that are in the worst condition, and therefore the individuals that are most vulnerable, may appear to be undisturbed when in reality they tolerate the disturbance because they cannot afford the energy or time to move away.

These two studies are examples of body condition affecting behavior. However, a study on the effect of habitat deterioration on lizards showed that behavior can also affect body condition. To study this effect, Amo et al. (2007) compared the behavior and body condition of lizards in ski slopes to those in natural areas. They found that habitat deterioration led to an increased perceived risk of predation, which led to an increase in movement speed when crossing these deteriorated, “risky”, areas. In turn, this elevated movement cost led to a decrease in body condition (Figure 2). Hence, the lizard’s behavior affected their body condition.

Figure 2. Figure showing the difference in body condition of lizards in natural and deteriorated habitats.

Together, these case studies provide an interesting overview of the potential answers to the question: does body condition affect behavior or does behavior affect body condition? The answer is that the relationship can go both ways. Ransom et al. (2004) showed that regardless of the treatment, behavior of female horses differed between body conditions, indicating that regardless of a disturbance, body condition affects behavior. Beale and Monaghan (2004) demonstrated that seabird reactions to disturbance differed between body conditions, indicating that disturbance studies should take body condition into account. And, Amo et al. (2007) showed that disturbance affects behavior, which consequently affects body condition.

Looking at the results from these three studies, I can envision finding similar results in my gray whale research. I hypothesize that gray whale behavior varies by body condition in everyday circumstances and when the whale is disturbed. Yet, I also hypothesize that being disturbed will affect gray whale behavior and subsequently their body condition. Therefore, what I anticipate based on these studies is a circular relationship between behavior and body condition of gray whales: if an increase in perceived risk affects behavior and then body condition, maybe those affected individuals with poor body condition will respond differently to the disturbance. It is yet to be determined if a sequence like this could ever be detected, but I think that it is important to investigate.

Reading through these studies, I am ready and eager to start digging into these hypotheses with our data. I am especially excited that I will be able to perform this investigation on an individual level because we have identified the whales in each drone video. I am confident that this work will lead to some interesting and important results connecting behavior and health, thus opening avenues for further investigations to improve conservation studies.

References

Beale, Colin M, and Pat Monaghan. 2004. “Behavioural Responses to Human Disturbance: A Matter of Choice?” Animal Behaviour 68 (5): 1065–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.07.002.

Ransom, Jason I, Brian S Cade, and N. Thompson Hobbs. 2010. “Influences of Immunocontraception on Time Budgets, Social Behavior, and Body Condition in Feral Horses.” Applied Animal Behaviour Science 124 (1–2): 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2010.01.015.

Amo, Luisa, Pilar López, and José Martín. 2007. “Habitat Deterioration Affects Body Condition of Lizards: A Behavioral Approach with Iberolacerta Cyreni Lizards Inhabiting Ski Resorts.” Biological Conservation 135 (1): 77–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2006.09.020.