By Lisa Hildebrand, PhD student, OSU Department of Fisheries & Wildlife, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

Over the roughly 2.5 years that I have researched the Pacific Coast Feeding Group (PCFG) of gray whales, I have thought more and more about what makes a population, a population. From a management standpoint, the PCFG is currently not considered a separate population or even a sub-population of the Eastern North Pacific (ENP) gray whales. Rather, the PCFG is most commonly referred to as a ‘sub-group’ of the ENP. In my opinion, there are valid arguments both for and against the PCFG being designated as its own population. I will address those arguments briefly at the end of this post, but first, I want you to join on me on a journey that is tangential to my question of ‘what makes a population, a population?’ and one that started at the last Marine Mammal Institute Monthly Meeting (MMIMM).

During 2021’s first MMIMM, our director Dr. Lisa Ballance proposed that we lengthen our monthly meeting duration from 1 hour to 1.5 hours. The additional 30 minutes was to allow for an open-ended, institute-wide discussion of a current hot topic in marine mammal science. This proposal was immediately adopted, and the group dove into a discussion about the discovery of a new baleen whale species in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico: Rice’s whale (Balaenoptera ricei). Let me pause here very briefly to reiterate – the discovery of a new baleen whale species!! The fact that anything as large as 12 m could remain undiscovered in our oceans is really quite fascinating and shows that our scientific quest will likely never run out of discoverable subjects. Anyway, the discovery of this new species is supported by several lines of evidence. Unfortunately (but understandably), MMI’s discussion of these topics had to cease after 30 minutes, however I had more questions. I wanted to know what had sparked the researchers to believe that they had discovered a new cetacean species.

I started my research by skimming through some news articles about the Rice’s whale discovery. In a Smithsonian Magazine article, I saw a quote by Dr. Patricia Rosel, the lead author of the study detailing Rice’s whale, that read: “But we didn’t have a skull.”. That quote made me pause. A skull? Is that what it takes to discover and establish a new species? This desired piece of evidence seemed rather puzzling and a little antiquated to me, given that the field of genetics is so advanced now and since it is no longer an accepted practice to kill a wild animal just to study it (i.e., scientific whaling). I backtracked through the article to learn that in the 1990s, renowned marine mammal scientist Dale Rice (after whom Rice’s whale was named) recognized that a small population of baleen whale occurred in the northeastern part of the Gulf of Mexico year-round. At the time, this population was believed to be a sub-population of Bryde’s whale. It wasn’t until 2008, that NOAA scientists were able to conduct a genetic analysis of tissue samples from this population, only to find that these whales were genetically distinct from other Bryde’s whales (Rosel & Wilcox 2014). Yet, this information was not enough for these whales to be established as their own species. A skull really was needed to prove that these whales were in fact a new species. Thankfully (for the scientists) but sadly (for the whale), one of these individuals stranded in Sandy Key, Florida, in 2019, and a dedicated team of stranding responders from Florida Fish and Wildlife, Mote Marine Lab, NOAA, Dolphins Plus, and Marine Animal Rescue Society worked tirelessly in difficult conditions to comprehensively document and preserve this animal. Through the diligent work of this, and previous, stranding response teams, Dr. Rosel and her team were provided the opportunity to examine the skull needed to determine population-status. The science team determined that the bones atop the skull around the blowhole provided evidence that these whales were not only genetically, but also anatomically, different from Bryde’s whales. It was this incident, triggered by that short quote in the Smithsonian article, that brought me to my journey of asking ‘what makes a species, a species?’.

Given that I had just read that Dr. Rosel needed a skull to establish Rice’s whale as its own species, I assumed that my search for ‘how to establish a new species’ would end quickly in me finding a list of requirements, one of which would be ‘must present anatomical/skeletal evidence’. To my surprise, my search did not end quickly, and I did not find a straightforward list of requirements. Instead, I discovered that my question of ‘what makes a species, a species?’ does not have a black-and-white answer and involves a lot of debate.

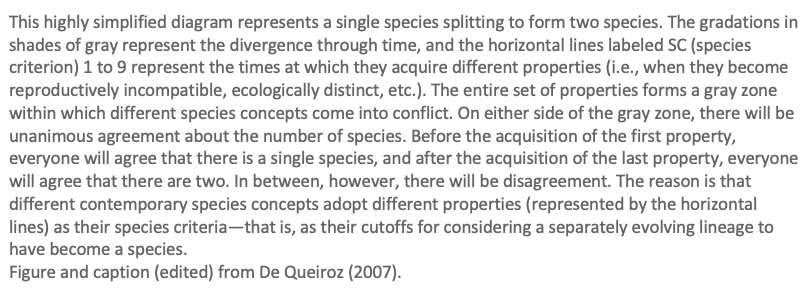

Kevin de Queiroz, a vertebrate, evolutionary, and systematic biologist who has published extensively on theoretical and conceptual topics in systematic and evolutionary biology, believes that the issue of species delimitation (‘what makes a species, a species?’) has been made more complicated by a larger issue involving the concept of species itself (‘what is a species?’) (De Queiroz 2007). To date, there are 24 recognized species concepts (Mayden 1997). In other words, there are 24 different definitions of what a species is. Perhaps the most common example is the biological species concept where a species is defined as a group of individuals that are able to produce viable and fertile offspring following natural reproduction. Another example is the ecological species concept whereby a species is a group of organisms adapted to a particular set of resources and conditions, called a niche, in the environment. Problematically, many of these concepts are incompatible with one another, meaning that applying different concepts leads to different conclusions about the boundaries and numbers of species in existence (De Queiroz 2007).

This large number of species concepts is due to the different interests of certain subgroups of biologists. For example, highlighting morphological differences between species is central to paleontologists and taxonomists, whereas ecologists will focus on niche differences. Population geneticists will attribute species differences to genes, while for systematists, monophyly will be paramount. It goes on and on. And so does the debate about the concept of species. It seems that there currently is not one clear, defined consensus on what a species is. Some biologists argue that a species is a species if it is genetically different, while others will insist that skeletal and morphological evidence must be present. From what I can tell, it seems that scientists describe and (attempt to) establish a new species by publishing their lines of evidence, after which experts in the field discuss and evaluate whether a new species should be established.

In the field of marine mammal science, the Society of Marine Mammalogy’s Taxonomic Committee is charged with maintaining a standard, accepted classification and nomenclature of marine mammals worldwide. The committee annually considers and evaluates new, peer-reviewed literature that proposes changes (including additions) to marine mammal taxonomy. I expect that the case of Rice’s whale will be on the committee’s docket this year. Given that Rosel and co-authors presented geographic, morphological, and genetic evidence to support the establishment of Rice’s whale, I would not be surprised if the committee adds it to their curated list.

After taking this dive into the ‘what makes a species, a species?’ question, let’s see if we can apply some of what we’ve learned to the ‘what makes a population, a population?’ question regarding the PCFG and ENP gray whales. Following the ecological species concept, an argument for the recognition of the PCFG as its own population would be that they occupy an entirely different environment during their summer foraging season than the ENP whales. Not only are the geographic ranges different, but PCFG whales also show behavioral differences in their foraging tactics and targeted prey. The argument against the PCFG being classified as its own population is largely supported by genetic analysis that has revealed ambiguous evidence that the PCFG and ENP are not genetically isolated from one another. While one study has shown that there is maternal cultural affiliation within the PCFG (meaning that calves born to PCFG females tend to return to the PCFG range; Frasier et al. 2011), another has revealed that mixing between ENP and PCFG gray whales on the breeding grounds does occur (Lang et al. 2014). So, even though these two groups feed in areas that are very far apart (ENP: Arctic vs PCFG: US & Canadian west coast) and certain individuals do show a propensity for a specific feeding ground, the genetic evidence suggests that they mix when on their breeding grounds in Baja California, Mexico. Depending on which species concept you align with, you may see better arguments for either side.

You may be wondering why it is important to even ponder questions like ‘what makes a species, a species?’ and ‘what makes a population, a population?’. Does it really matter if the PCFG are considered their own population? Would anything really change? The answer is, most likely, yes. If the PCFG were to be recognized as their own population, it would likely have an immediate effect on their conservation status and subsequently on how the population needed to be managed. Rather than being under the umbrella of a large, (mostly) stable population of ~25,000 individuals, the PCFG would consist of only ~250 individuals. A group this small would possibly be considered “endangered”, which would require much stricter monitoring and management to ensure that their numbers did not decline from year to year, especially due to anthropogenic activities.

For a long time, I felt like taxonomy was a bit of an archaic scientific field. In my mind, it was something that biologists had focused their time and energy on in the 18th century (most notably Carl Linnaeus, whose taxonomic classification system is still used today), but something that many biologists have moved on from focusing on in the 21st century. However, as I have developed and grown over the last years as a scientist, I have learned that scientific disciplines are often heavily intertwined and co-dependent on one another. As a result, I am able to see the enormous value and need for taxonomic work as it plays a large part in understanding, managing, and ultimately, conserving species and populations.

Literature cited

De Queiroz, K. 2007. Species concepts and species delimitation. Systematic Biology 56(6):879-886.

Frasier, T. R., Koroscil, S. M., White, B. N., and J. D. Darling. 2011. Assessment of population substructure in relation to summer feeding ground use in the eastern North Pacific gray whale. Endangered Species Research 14:39-48.

Lang, A. R., Calambokidis, J., Scordino, J., Pease, V. L., Klimek, A., Burkanov, V. N., Gearin, P., Litovka, D. I., Robertson, K. M., Mate, B. R., Jacobsen, J. K., and B. L. Taylor. 2014. Assessment of genetic structure among eastern North Pacific gray whales on their feeding grounds. Marine Mammal Science 30(4):1473-1493.

Mayden, R. L. 1997. A hierarchy of species concepts: the denouement of the species problem in The Units of Biodiversity – Species in Practice Special Volume 54 (M. F. Claridge, H. A. Dawah, and M. R. Wilson, eds.). Systematics Association.

Rosel, P. E., and L. A. Wilcox. 2014. Genetic evidence reveals a unique lineage of Bryde’s whale in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico. Endangered Species Research 25:19-34.