By Abby Tomita, undergraduate student, OSU College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences

From long days in Newport performing the patience-testing task of bomb calorimetry, to spending hours transfixed by the microscopic world that exists in our oceans, I recently got an amazing glimpse into the world of marine biological research working with PhD student Rachel Kaplan. She has been an amazing teacher to my fellow intern Hadley and I, showing us the basics of the research process and introducing us to so many wonderful people at NOAA and the GEMM Lab. I am in my third year studying oceanography here at OSU and had no real lab experience before this, so I was eager to explore this area of research, and not only learn new information about our oceans, but also to see the research process up close and personal.

After being trained by Jennifer Fisher, a NOAA Research Fisheries Biologist, I sorted through zooplankton samples collected on the R/V Bell M. Shimada from the Northern California Current region. This data will be used to get an idea of where krill are found throughout the year, and in what abundances. Though my focus was mainly on two species of krill, I also found an assortment of other organisms, such as larval fish, squid, copepods, crabs, and tons of jellies, which were super interesting to see.

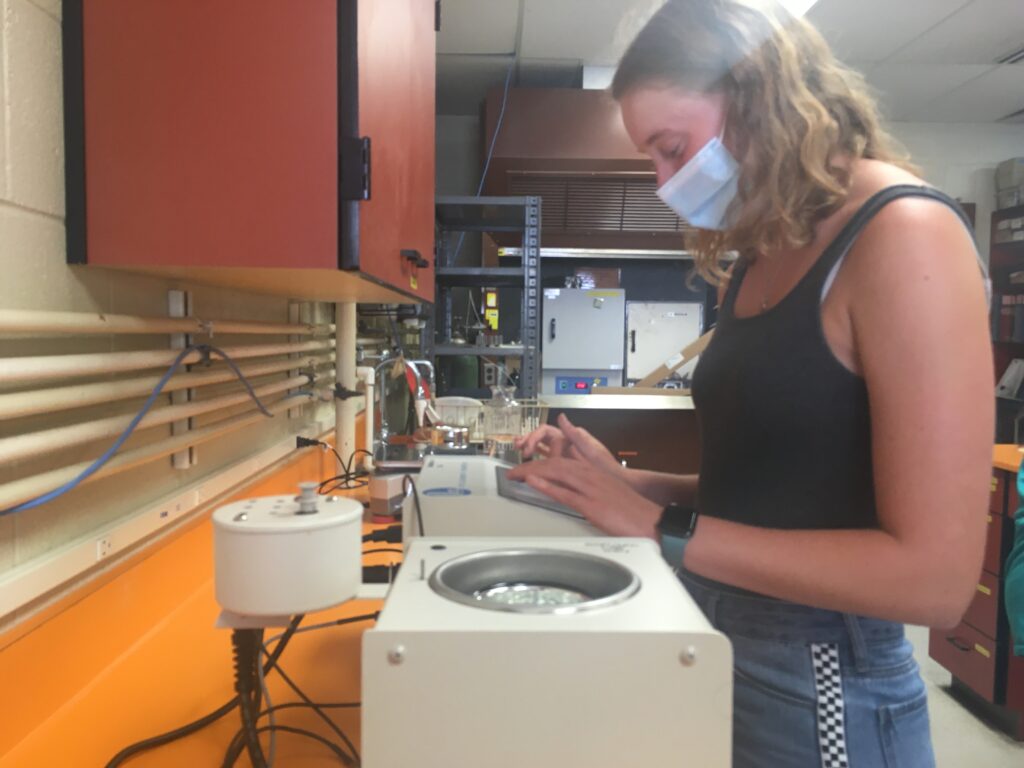

I also studied krill through a technique called bomb calorimetry, which is not for the faint of heart! It takes a tough soul to be able to put these complex little creatures into a mortar and pestle and grind them into a dust that hits your nose like pepper. They then take their final resting place into the bomb calorimetry machine (which can and will find something to fuss over) until it finally manages to ignite and dispose of the krill’s remains. The light that guided me through this dark tunnel was the knowledge that these sacrificial krill were taken in the name of science, with the aim of eventually decreasing whale entanglements.

That, and Rachel’s contagious positivity. In the early stages, we would spend the majority of our time troubleshooting after constant “misfires”, in which the machine fails to combust the sample properly. Bomb calorimetry involves many tedious steps, and working with such small quantities of tissue – a single krill could weigh 0.01 grams or even less – poses a plethora of its own challenges. One of my biggest takeaways from this experience was to have patience with this kind of work and know when to take a much-needed dance break. Things often do not work out according to plan, and getting to see first-hand how to adapt to confounding variables and hitches in the procedure was an invaluable lesson.

I also got to see how collaborative the research process is. We received helpful advice from other members of the GEMM Lab at lunch, as well as constant help from our esteemed Resident Bomb Cal Expert, Elizabeth Daly. It was comforting for me to see that even when you are doing independent research, you are not expected to only work alone, and there can be so much community in higher level research.

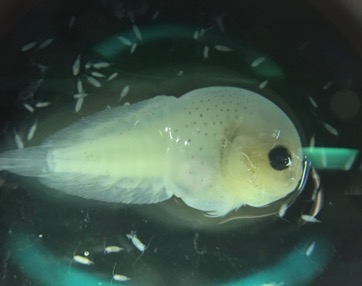

Female Thysanoessa spinifera krill (photos by Abby Tomita).

Did you enjoy this blog? Want to learn more about marine life, research, and conservation? Subscribe to our blog and get a weekly message when we post a new blog. Just add your name and email into the subscribe box below.