By Rachel Kaplan, PhD student, OSU College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences and Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

Returning to a place you once lived always shows how much you and the world around you have changed, offering a new perspective on the time away and where you are now. I’m writing this from my old office at Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in East Boothbay, Maine, where I worked before moving out to Oregon to join the GEMM Lab and start graduate school at OSU. Being back in Maine has made me reflect on how much I’ve learned over the last year, and given me the opportunity to think about what’s ahead.

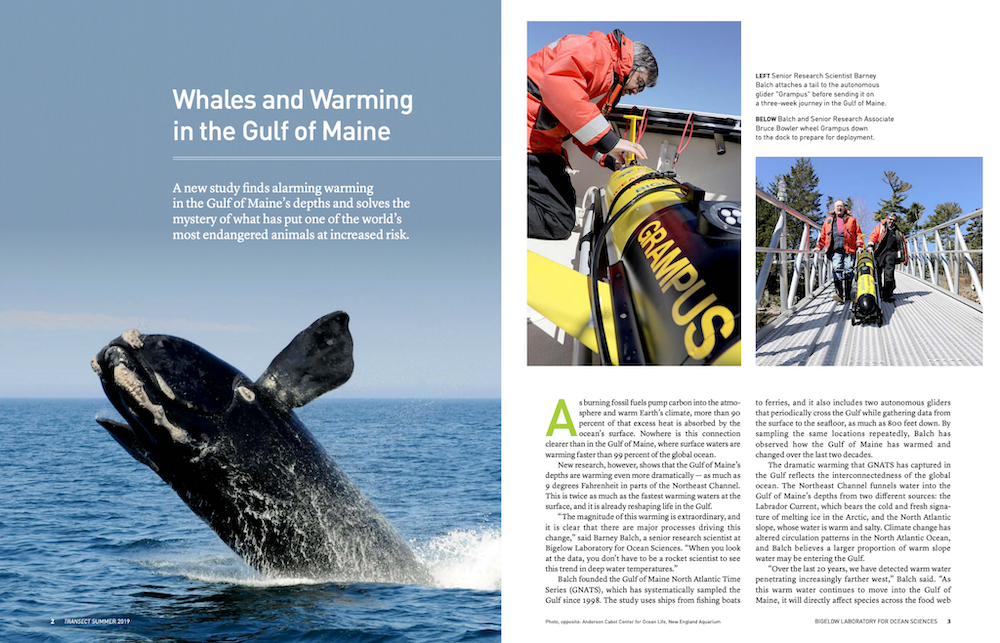

As a science communications specialist at Bigelow for three years, much of my work involved quickly getting up to speed on new research and writing articles for a general audience about important ocean processes. My first year of grad school has both deepened and broadened my perspective on the ocean, prodding me to think at telescoping temporal and spatial scales. I can tell that I think about the ocean differently now.

Over the last year, my coursework in ocean ecology and biogeochemistry surveyed the physical and chemical workings of the ocean, marine ecosystem dynamics, and the global cycles that control much of life on earth. Through lab activities and fieldwork, I began learning about whales and the marine system off the coast of Oregon, and how to ask questions that occupy the intersection between whales and their environment.

This work and learning have made me think in a new way about whales as agents of biogeochemical cycling: how do they shuttle nutrients across large distances and affect global cycles? In what ways is the biogeography of whales an expression of the global patterns of light availability and nutrient fluxes that support their prey? How is it possible to detangle and encapsulate all of the relevant variability of a natural system into a mathematical model?

All these questions were churning in my mind at the start of this trip, as I spent the bus ride from Boston to Maine reading papers for our monthly GEMM lab meeting. I also remembered the first meeting that I joined, when I was so intimidated that I couldn’t imagine discussing research with this impressive group. This time, I was just as in awe as ever of the lab, but a bit more confident in wielding acronyms and sharing ideas.

I actually attended my first GEMM Lab meeting while still working in Maine, in July 2020. I was joined by my friends’ one-year-old daughter, who alternately tried to chime in on the meeting and shut my laptop. Now, she is a chatty two-year-old kid and newly a big sister. The new baby became part of my PhD this week too, snoozing in my lap as I edited an abstract.

Often, it’s only seeing my friends’ children grow that shows me how much time has passed. This time, I can feel it in myself, as well. I’m excited to have made it through the first year of coursework and to be learning to formulate research questions and think about ocean systems in new ways. I’m happy to be back in this place that inspired me to pursue a PhD, and to be able to share my own work and knowledge with former colleagues.

I gained so much during my time here at Bigelow: the communication and outreach skills in my job, inspiration from the scientific curiosity and passion of my colleagues, and the support of all these people who reassured me that I would get into grad school and that doing a PhD is a good idea. I’m so happy to be able to carry this support and momentum forward with me through the rest of grad school, and excited to return to Oregon and keep going.