By Dr. Dawn Barlow, Postdoctoral Scholar, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab

Recently, I had the opportunity to attend the Effects of Climate Change on the World’s Ocean (ECCWO) conference. This meeting brought together experts from around the world for one week in Bergen, Norway, to gather and share the latest information on how oceans are changing, what is at risk, responses that are underway, and strategies for increasing climate resilience, mitigation, and adaptation. I presented our recent findings from the EMERALD project, which examines gray whale and harbor porpoise distribution in the Northern California Current over the past three decades. Beyond sharing my postdoctoral research widely for the first time and receiving valuable feedback, the ECCWO conference was an incredibly fruitful learning experience. Marine mammals can be notoriously difficult to study, and often the latest methodological approaches or conceptual frameworks take some time to make their way into the marine mammal field. At ECCWO, I was part of discussions at the ground floor of how the scientific community can characterize the impacts of climate change on the ecosystems, species, and communities we study.

One particular theme became increasingly apparent to me throughout the conference: as the oceans warm, what are “anomalous conditions”? There was an interesting dichotomy between presentations focusing on “extreme events,” “no-analog conditions,” or “non-stationary responses,” compared with discussions about the overall trend of increasing temperatures due to climate change. Essentially, the question that kept arising was, what is our frame of reference? When measuring change, how do we define the baseline?

Marine heatwaves have emerged as an increasingly prevalent phenomenon in recent years (see previous GEMM Lab blogs about marine heatwaves here and here). The currently accepted and typically applied definition of a marine heatwave is when water temperatures exceed a seasonal threshold (greater than the 90th percentile) for a given length of time (five consecutive days or longer) (Hobday et al. 2016). These marine heatwaves can have substantial ecosystem-wide impacts including changes in water column structure, primary production, species composition, distribution, and health, and fisheries management such as closures and quota changes (Cavole et al. 2016, Oliver et al. 2018). Through some of our own previous research, we documented that blue whales in Aotearoa New Zealand shifted their distribution (Barlow et al. 2020) and reduced their reproductive effort (Barlow et al. 2023) in response to marine heatwaves. Concerningly, recent projections anticipate an increase in the frequency, intensity, and duration of marine heatwaves under global climate change (Frölicher et al. 2018, Oliver et al. 2018).

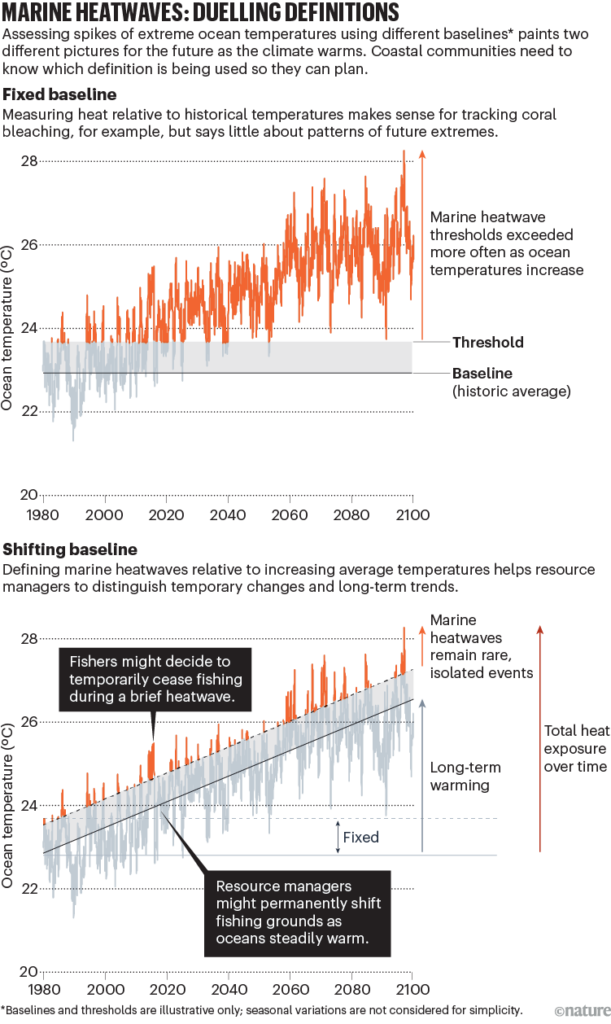

However, as the oceans continue to warm, what baseline do we use to define anomalous events like marine heatwaves? Members of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Marine Ecosystem Task Force recently put forward a comment article in Nature, proposing revised definitions for marine heatwaves under climate change, so that coastal communities have the clear information they need to adapt (Amaya et al. 2023). The authors posit that while a “fixed baseline” approach, which compares current conditions to an established period in the past and has been commonly used to-date (Hobday et al. 2016), may be useful in scenarios where a species’ physiological limit is concerned (e.g., coral bleaching), this definition does not incorporate the combined effect of overall warming due to climate change. A “shifting baseline” approach to defining marine heatwaves, in contrast, uses a moving window definition for what is considered “normal” conditions. Therefore, this shifting baseline approach would account for long-term warming, while also calculating anomalous conditions relative to the current state of the system.

Why bother with these seemingly nuanced definitions and differences in terminology, such as fixed versus shifting baselines for defining marine heatwave events? The impacts of these events can be extreme, and potentially bear substantial consequences to ecosystems, species, and coastal communities that rely on marine resources. With the fixed baseline definition, we may be headed toward perpetual heatwave conditions (i.e., it’s almost always hotter than it used to be), at which point disentangling the overall warming trends from these short-term extremes becomes nearly impossible. What the shifting baseline definition means in practice, however, is that in the future temperatures would need to be substantially higher than the historical average in order to qualify as a marine heatwave, which could obscure public perception from the concerning reality of warming oceans. Yet, the authors of the Nature comment article claim, “If everything is extremely warm all of the time, then the term ‘extreme’ loses its meaning. The public might become desensitized to the real threat of marine heatwaves, potentially leading to inaction or a lack of preparedness.” Therefore, clear messaging surrounding both long-term warming and short-term anomalous conditions are critically important for adaptation and resource allocation in the face of rapid environmental change.

While the findings presented and discussed at an international climate change conference could be considered quite disheartening, I left the ECCWO conference feeling re-invigorated with hope. Crown Prince Haakon of Norway gave the opening plenary and articulated that “We need wise and concerned scientists in our search for truth”. Later in the week, I was a co-convenor of a session that gathered early-career ocean professionals, where we discussed themes such as how we deal with uncertainty in our own climate change-related ocean research, and importantly, how do we communicate our findings effectively. Throughout the meeting, I had formal and informal discussions about methods and analytical techniques, and also about what connects each of us to the work that we do. Interacting with driven and dedicated researchers across a broad range of disciplines and career stages gave me some renewed hope for a future of ocean science and marine conservation that is constructive, collaborative, and impactful.

Now, as I am diving back in to understanding the impacts of environmental conditions on harbor porpoise and gray whale habitat use patterns through the EMERALD project, I am keeping these themes and takeaways from the ECCWO conference in mind. The EMERALD project draws on a dataset that is about as old as I am, which gives me some tangible perspective on how things have things changed in the Northern California Current during my lifetime. We are grappling with what “anomalous” conditions are in this dynamic upwelling system on our doorstep, whether these anomalies are even always bad, and how conditions continue to change in terms of cyclical oscillations, long-term trends, and short-term events. Stay tuned for what we’ll find, as we continue to disentangle these intertwined patterns of change.

Did you enjoy this blog? Want to learn more about marine life, research, and conservation? Subscribe to our blog and get a weekly alert when we make a new post! Just add your name into the subscribe box below!

References

Amaya DJ, Jacox MG, Fewings MR, Saba VS, Stuecker MF, Rykaczewski RR, Ross AC, Stock CA, Capotondi A, Petrik CM, Bograd SJ, Alexander MA, Cheng W, Hermann AJ, Kearney KA, Powell BS (2023) Marine heatwaves need clear definitions so coastal communities can adapt. Nature 616:29–32.

Barlow DR, Bernard KS, Escobar-Flores P, Palacios DM, Torres LG (2020) Links in the trophic chain: Modeling functional relationships between in situ oceanography, krill, and blue whale distribution under different oceanographic regimes. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 642:207–225.

Barlow DR, Klinck H, Ponirakis D, Branch TA, Torres LG (2023) Environmental conditions and marine heatwaves influence blue whale foraging and reproductive effort. Ecol Evol 13:e9770.

Cavole LM, Demko AM, Diner RE, Giddings A, Koester I, Pagniello CMLS, Paulsen ML, Ramirez-Valdez A, Schwenck SM, Yen NK, Zill ME, Franks PJS (2016) Biological impacts of the 2013–2015 warm-water anomaly in the northeast Pacific: Winners, losers, and the future. Oceanography 29:273–285.

Frölicher TL, Fischer EM, Gruber N (2018) Marine heatwaves under global warming. Nature 560.

Hobday AJ, Alexander L V., Perkins SE, Smale DA, Straub SC, Oliver ECJ, Benthuysen JA, Burrows MT, Donat MG, Feng M, Holbrook NJ, Moore PJ, Scannell HA, Sen Gupta A, Wernberg T (2016) A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog Oceanogr.

Oliver ECJ, Donat MG, Burrows MT, Moore PJ, Smale DA, Alexander L V., Benthuysen JA, Feng M, Sen Gupta A, Hobday AJ, Holbrook NJ, Perkins-Kirkpatrick SE, Scannell HA, Straub SC, Wernberg T (2018) Longer and more frequent marine heatwaves over the past century. Nat Commun 9:1–12.