Imogen Lucciano, Graduate Student, OSU Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, & Conservation Sciences, Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Lab. Marissa Garcia, Graduate Student, Cornell Department of Ornithology Center for Conservation Bioacoustics.

There is nothing quite like the excitement of starting a fresh project, and the newly organized Holistic Assessment of Living marine resources off the Oregon coast (HALO) project team was alive with it on 8 October as we prepared our various elements of research gear aboard the R/V Pacific Storm in the Newport bayfront (Fig 1). The weather was predicted suitable enough for our 24-hour trip out along the Newport Hydrographic line (NHL; Fig 2), and so we focused on the questions of whether we had remembered to pack each necessary piece of equipment, whether we had sufficiently charged and calibrated each bit of gear, whether we had enough snacks, and the most looming question of all, what would we see and hear when we get out there? The species guessing game only enhanced the thrill of our departure.

Figure 1. The R/V Pacific Storm docked at the Newport bayfront. Photo: Rachel Kaplan.

The HALO project aims to fill gaps in knowledge on the abundance and distribution of cetaceans off the Oregon coast, and relative to ongoing climate change and marine renewable energy development projects along the Oregon coast. The core of the HALO project is deployment of three hydrophones to record year-round cetacean vocalizations in the same area where we will conduct visual line surveys for cetaceans monthly in addition to mapping prey. Needless to say, we (the grad student authors of this blog) feel humbled and grateful to be on the project – not to mention, eager to gain our sea legs like the rest of the pros on the team and boat crew (much sea sickness meds were at the ready!).

This HALO team is well stacked, engaging the expertise and specialties of researchers from three different schools of science. Leigh Torres of the Marine Mammal Institute (MMI)’s GEMM lab (assisted by newcomer graduate student, Miranda Mayhall/coauthor of this post) brings to the project the knowledge of visual survey distance sampling data collection and analysis and will work alongside Craig Hayslip of MMI who will serve as lead visual observer. The visual sightings will inform us on cetacean occurrence patterns in the region. Since cetaceans also spend a great deal of time underwater, Holger Klinck, an expert bioacoustician from Cornell University and affiliate MMI professor (with graduate student Marissa Garcia, also a coauthor of this blog) will oversee the deployment of specialized hydrophones along our research line to record acoustic data. After the hydrophones are deployed, and while we are on-survey looking for cetaceans, we will also run a EK60 transducer (A.K. echosounder) to record backscatter data on prey in the area. This aspect of HALO brings in the third element of research from OSU’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences (CEOAS) Zooplankton Ecology Lab, Kim Bernard who is leading the effort to collect and analyze prey data. During this first voyage, Rachel Kaplan, a grad student of both the GEMM lab and Zooplankton Ecology Labs, came along to run the echosounder and ensure data quality.

Figure 2. HALO’s research track-line: a 40-mile stretch along the Newport Hydrographic Line (NHL) from NH65 to NH25. The three points indicate the locations of the three deployed hydrophones.

With the sun nearly set, the R/V Pacific Storm left the dock at 7pm, pushing from Yaquina Bay out to the Pacific along the NHL hopping over swells that rocked the boat. Despite our strong-willed confidence, it was tough then to focus on anything but maintaining personal physiological equilibrium. Darkness surrounded the vessel, and we wouldn’t be able to see much of the Pacific Ocean until morning. It would take us nearly eleven hours to reach our first destination, 65 miles offshore (NH65) at which point all the activities would begin. All we could do was brace through the evening and hope that by dawn the dizziness would subside. We had field work adventures ahead! So, the focus went from extreme high energy to tucking in and allowing the Storm’s highly experienced crew to maintain watch and bring us to our first destination.

Figure 3. The research lab room on the R/V Pacific Storm with four eager scientists just as team HALO departed Yaquina Bay; from the left Holger Klinck, Marissa Garcia, Rachel Kaplan & Leigh Torres. Photo: Miranda Mayhall.

At sunrise, the team rose to their feet, and we (the grad students) did what we could to muster the energy to crawl up the stairs, snap on lifejackets and ample out on the boat deck. Despite our condition, we looked out to a sight unlike anything we had ever seen before. The ocean was a deep purple, with flecks of orange bordering the horizon behind fluffy, indigo clouds. We were at NH65, and at this point it was time to deploy the first Rockhopper, a specialized hydrophone developed at Cornell lab of Ornithology, with the capability of recording at a high sampling rate (394 kHz), which allows it to detect and record most marine mammal species. In this case, we were recording at 197 kHz, only leaving our porpoises from the recordings.

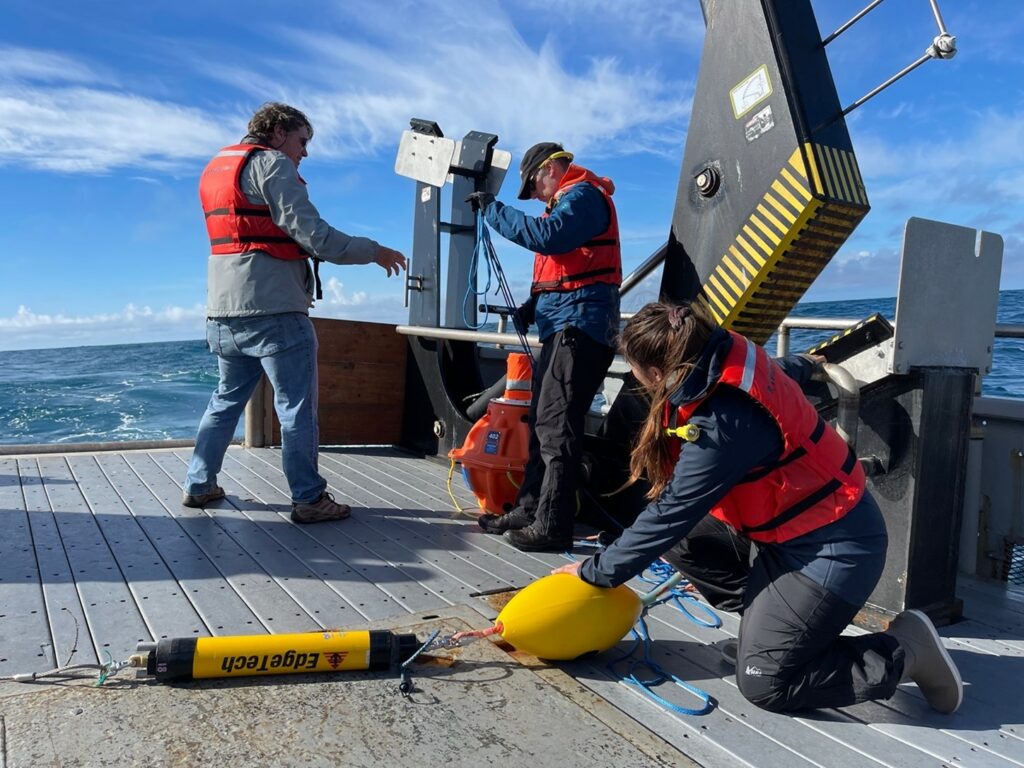

Although the acoustic team has extensively prepared the hydrophones for deployment, nothing quite prepared us for focusing on the final connections and tests on the back deck while the boat rocked back and forth. The team initiated the Rockhopper for recording, and then we proceeded with setting up the mooring — connecting the Rockhopper to the acoustic release, float, and weights. We then slowly slid it off the edge of the boat, and there it went into the ocean, where it will record for six months, approximately 3,000 meters under the surface.

Figure 4. The HALO team prepared the Rockhopper (the orange orb-like device) for deployment; from the left, Craig Hayslip, Holger Klinck, and Marissa Garcia. Photo: Rachel Kaplan.

Once the first Rockhopper was deployed, making its way to the ocean floor, the “transducer pole” was deployed off the side of the vessel to collect echosounder data and the long endeavor of conducting visual survey for the length of the research line began. Observers were glued to binoculars, scouring the sea for the presence of cetaceans, as the ocean swell rocked the boat on our journey eastward. Those with an appetite nibbled on Tony’s Chocoloney chocolate bars (Thanks, Leigh!), breaking off pieces and passing around the bar to each visual observer — an optimal fuel for remaining attentive.

Figure 5. HALO team up on the flying bridge; Observers clockwise from the lower left: Leigh Torres, Marissa Garcia, Craig Hayslip, Miranda Mayhall, Holger Klinck.

During visual survey effort, we observe from the flying bridge the entire front 180 degrees of the vessel trackline, all the while recording data on where we do and don’t see cetaceans (presence and absence data). During this survey effort we record the sighting conditions (visibility, sea state, glare), and when we see cetaceans we record the distance to the marine mammals from the boat, the species identification, and the number of animals in the sighting. We use a program called SeaScribe to collect our data. As we use the data collection protocols on each of the 12 planned monthly surveys, we will obtain a valuable, standardized dataset that can be analyzed relative to environmental conditions and in comparison, to the acoustic data to understand cetacean distribution patterns. The survey pressed on, and all the while the echosounder was actively recording prey availability data, with Rachel Kaplan at the control.

Figure 6. Rachel Kaplan monitoring the incoming data from the transducer on the SIMRAD EK60. Photo: Marissa Garcia.

Over the course of the survey, the visual team spotted northern right whale dolphins, a fin whale, a small group of killer whales and many scattered humpback whales. All three Rockhoppers were deployed at their intended locations at NH65, NH45, and then NH25. The echosounder successfully collected backscatter data for the duration of the survey, and interestingly we noticed increased prey on the echosounder at the same time as we observed the humpbacks. Already we are detecting connections between the environment and cetaceans!

Figure 8. Fin whale spotted while on our first HALO survey. Photo: Leigh Torres, NOAA/NMFS permit # 21678

After nearly twelve hours conducting field work, the shoreline was close in sight, and we stopped our survey effort. For the first time all day, we all collectively sat in the vessel’s laboratory, finally putting our feet up to rest. We pulled back into Newport harbor around 7:00 pm, with the first HALO cruise successfully in the books. And though we visually observed many cetaceans and collected prey data, we still couldn’t help wondering what the Rockhoppers were recording at the bottom of the ocean. The thought of getting back out there for more surveys and retrieving the sound data keeps our momentum in full swing. For the next 11 months (and hopefully longer!) we will conduct the same 24 hr. cruise. The future is exciting, and we can’t wait to report back on our future trips and research findings.

Figure 9. The HALO team walking along the dock to their cars in Newport, Oregon, heading home after cruise #1. Photo: Miranda Mayhall.

This project was funded by sales and renewals of the special Oregon whale license plate, which benefits MMI. We gratefully thank all the gray whale license plate holders, who made this research trip possible.

Amazing work